Joseph Brodsky: Loving, Leaving and Living

/ Главная / Russkiy Mir Foundation / Publications / Joseph Brodsky: Loving, Leaving and LivingJoseph Brodsky: Loving, Leaving and Living

On Washerwoman Bridge, where you and I

stood like two hands of a midnight clock

embracing, soon to part, not for a day

but for all days – this morning on our bridge

a narcissistic fisherman,

forgetting his cork float, stares goggle-eyed

at his unsteady river image.

…

So let him gaze

into our waters, calmly, at himself,

and even come to know himself. The river

is his by right today. It's like a house

in which new tenants have set up a mirror

but have not yet moved in. *

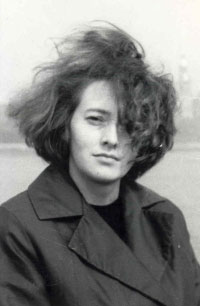

These lines are to be found in many anthologies of Joseph Brodsky’s poetry. And above this verse we find the initials F.W., the initials of Faith Wigzell. In the fifteen years since the poet’s death, she has published nothing about her friendship with him nor has she given any interviews on the subject nor published their correspondence. She has also refrained from commenting on the poems he dedicated to her.

* * *

– How did you meet Brodsky? What kind of first impression did he make on you?

– I believe it was March 1968. I had come to Leningrad for a six-week research visit, connected with my PhD at London University.

– And what did this work entail?

– I was studying early Russian literature.

– Really!

– Oh, that’s nothing! Try asking me what I do now.

– And what do you do?

– I am currently writing about commercial magic in Russia today.

– I don’t even know what that is…

– Well, it includes witches, fortune tellers, magicians and astrologists…

– That’s great, but let’s get back to Brodsky.

– Fine. I arrived in Leningrad and straight away phoned my old friends Romas and Elia Katilius. Back in 1963-64 I was studying in Leningrad and it was then that I met the Katiliuses and Diana Abaeva, later to become Diana Myers and to work with me at London University. But that would come later.

It was back then, in the early 1960s, that we met and became friends. They were wonderful people – kind, engaging, loving poetry and art, and saw the Soviet government for what it was worth. They were scientists: Romas was a theoretical physicist at the semiconductor institute. Diana, on the other hand, was in the humanities’ field.

So, in short, I called the Katiliuses; they were very pleased and invited me over that evening. I went of course to their enormous room in a communal apartment on Tchaikovsky Street… But apart from my friends I there found a young man whom I had not previously met. He immediately attracted my attention.

– Why?

– Firstly, he had this very unusual smile.

– What do you mean by unusual?

– How can I put it? It was a shy or, more precisely, a timid smile. Yes, yes, timid. And his voice…

– His voice?

– Well, it was something special… Never since then have I encountered such a voice. When he read his poetry his voice made an astonishing impression …

– And that was Brodsky?

– And that was Brodsky. It turned out that he had been friendly with the Katiliuses for a long time, and with Diana as well. The Katiliuses had a young child, so guests could not overstay their welcome. Late in the evening Joseph and I went out on Tchaikovsky Street, and he walked me back to the hotel. And so that’s how it all began.

– And you spoke about literature, of course?

– Not only, not only… (Faith laughs) As it turns out Joseph and I had another friend in common – Tolya Naiman. When I found out, I decided to give them both a present. I had brought with me from London a large bottle, a litre I think, of whisky. At that time in Russia whisky wasn’t to be found in ordinary shops. They were more than delighted to accept, but what happened next seemed to me downright horrible: the two of them proceeded to drink the entire bottle in the course of the evening. I was absolutely stunned. I asked: why did you drink the whole bottle? They just shrugged.

* * *

When her six weeks in Leningrad had come to an end and she had to go home, to London, it turned out that in addition to new impressions, research material and attractive souvenirs, she had packed something much more serious: an offer of heart and hand from the poet Joseph Brodsky.

* * *

She returned to London and four years later married an American who lived in England. In 1972, when Brodsky was expelled from the USSR, he flew to London together with the great W.H. Auden for an international poetry festival. Faith was expecting her first child. Seeing her pregnant was a shock for Brodsky. She subsequently tried to keep their meetings to a minimum, so as not to cause him any distress.

* * *

– In 1978 my husband and I split up. From time to time I would see Joseph, but I always left the initiative up to him… Once he appeared with Maria, his wife. They came to London from Sweden, where they had just got married. He wanted me to meet her.

He came up to me during a reception at the British Academy, where he told me he would like me to meet her, and that she looked a bit like me, when I was younger (this I took as a great compliment). As I recall, Maria and I shook hands but no more, there being so many people dying to talk to them.

We also saw each other after it was announced he had won the Nobel Prize. He was in London. I think he was staying at Diana Myers’ place in Hampstead. When he found out that he had been awarded the prize, Diana planned a celebratory meal and he asked me over. It was a really happy occasion – I have to add that Diana is a great cook…

– How do you relate to the poems which he dedicated to you: are the just Brodsky’s poems or are they poetic letters to Faith Wigzell?

– I cannot see them as simply Brodsky’s poems. I read them for myself.

– In general, do you like his poetry?

– Above all else, I like the poems he wrote in Russia, in Leningrad and in Norenskaya. The period when he began to translate John Donne.

– Which of his essays do you like?

– What he wrote in Venice. Watermark.

– Have you seen his grave on the isle San Michele of Venice?

– No, I haven’t. Actually, I have only been to his beloved Venice once, when I was young.

– I once happened to visit San Michele when Venice was besieged by a snowstorm and Brodsky’s gravestone was covered by a big pile of snow, just like back in his beloved Leningrad…

– Yes, yes, he loved snow very much, big snowdrifts in particular…

* * *

We stood around a little longer in silence: I recalled the snow-covered San Michele. Of what she was thinking, I cannot say. Outside the hospitable house where we had met, it was a late autumn evening in London. To be honest, I was overwhelmed by a feeling of gratitude towards Faith Wigzell… for the fact that Brodsky was happy with her and for the fact that she spoke of him with such warmth and love.

I now think that above all else this is a story about fate, the fate that put an end to their brief time together on this earth. And perhaps for this reason such lines as these will remain alive forever:

Here is our meeting place. A grotto

beyond the mists. A gazebo in the clouds.

A warm and welcoming sanctuary.

A view; and one of the best at that.

…

So this is what we two were given.

For a while. Forever. Till the grave.

Invisible to one another, but

from up there visible both…**

Yuri Lepsky

Rossiyskaya Gazeta

* Washerwoman Bridge (Прачечный мост), 1968, translation by George Kline (several lines omitted)

** Excerpts from ‘Song without Music’ (Пенье без музыки), 1969

New publications

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.  Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.

Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.  When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.  Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."

Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."  "Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...

"Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...