Proud of Our People! Nikolay Przhevalsky, Explorer of Central Asia

/ Главная / Russkiy Mir Foundation / Publications / Proud of Our People! Nikolay Przhevalsky, Explorer of Central AsiaProud of Our People! Nikolay Przhevalsky, Explorer of Central Asia

Anna Efremova

Nikolay Przhevalsky. Photo credit: wikimedia.org

Nikolay Przhevalsky was born in Smolensk Province on March 31 (April 12), 1839. He became an international celebrity during his lifetime, having uncovered the vast expanses of Asia for Europeans. He was a brave pioneer, a patriot of Russia, as well as an outstanding scholar-naturalist.

Nikolay Przhevalsky was an outstanding Russian traveler and explorer. He was descended from the Russified Polish gentry in Smolensk. Kazimir Przhevalsky, his grandfather, was brought up in a Jesuit school in Polatsk, then he ran away and converted to Orthodoxy. Nikolay's father, Mikhail Przhevalsky, was a faithful servant to the Russian crown and took part in the suppression of the Polish uprising of 1830-31. The traveler-to-be followed in his footsteps and participated in the suppression of the Polish uprising of 1863-64.

The family adhered to the Old Testament morals. Nikolay received a quite Spartan upbringing, and some rectitude and indelicacy of his personality had an impact on him later in life. Hunting and fishing were Nikolay's main hobbies during his childhood, and then throughout his life.

Nikolay was independent from a young age. Other people's opinions didn't really matter to him. Having been a leader at school, he tended to be fair and was respected by his classmates. Education was easy for him. Nikolay Przhevalsky was gifted with a photographic memory. This rare talent served him well. He was very successful at playing cards, and he was even nicknamed the "golden pheasant". Mr. Przhevalsky accumulated some capital by playing cards. Later on, he used it to arrange his first travels (the funds allocated by the treasury were not very generous at first).

Officer, dreamer, hunter

After completing the course in the Smolensk grammar school in 1855, he joined the Ryazan Infantry Regiment as a non-commissioned officer. Then he served as an officer in the Polatsk Regiment, however, the provincial regimental life disappointed the gifted young man quite fast. He spent his free time hunting, reading a lot, collecting plants, and dreaming of traveling to unexplored lands. His European contemporaries were attracted to Africa, yet Africa was very far away. So, Mr. Przhevalsky requested to be transferred to the Far East, which was still barely explored at that time. His superiors did not endorse the report, and then the young officer joined the Nikolayev General Staff Academy.

It was here that Mr. Przhevalsky began to pursue science. The Russian Geographical Society noticed his work "Military and Static Review of the Priamurye Territory" and elected him its fellow.

Among other things, Nikolay Przhevalsky offered a daring geopolitical project in the above article. It was aimed at exploring the Amur basin and the Sungari River, its tributary, so that later Russians would be able to occupy Manchuria, build up trading relations with rich China, and strengthen their influence in the Celestial Empire.

Having graduated from the academy, Mr. Przhevalsky became a teacher of history and geography at the Warsaw Cadet School. He studied diligently in his spare time. He researched zoology and botany and compiled a good geography textbook. He carefully studied the geography of Asia as he wished to travel to that part of the world.

At last Nikolay Przhevalsky's perseverance was rewarded. In 1867, he was assigned to the General Staff and transferred to the East Siberian District.

From the Ussuri River to the Pacific Ocean

Having arrived in Irkutsk, Mr. Przhevalsky was sent on a mission to the Ussuri Krai. The Siberian Department of the Geographical Society contributed to the organization of his first expedition by providing him with topographic and astronomical tools and a modest amount of money.

Nikolay Przhevalsky was excited. "Three days later, that is, on May 26, I am going to the Amur River, then to the Ussuri River, Lake Khanka, and to the shores of the Pacific Ocean near the borders of Korea. All in all, the expedition is going to be great. I'm so delighted! Indeed, I have an enviable fate and a challenging duty to explore areas where no European has gone before," he described the purpose of the expedition in one of his letters.

The travelers cruised along the Ussuri River for more than three weeks, a wild, forested area at the time. They traveled partly by boat, partly by making their way up the shore. They shot game and collected plants and insects along the way.

Then the detachment of a few people headed to Lake Khanka, which was inhabited by a lot of birds. After that, the travelers went to the coast of the Sea of Japan. In winter, when the weather became freezing cold, they undertook a hard expedition to the southern part of the Ussuri Krai.

At the beginning of January 1868, the travelers returned to the stanitsa of Busse. More than 620 miles had been covered during the expedition. A collection of plants and a large ornithological collection had been compiled. Furthermore, Nikolay Przhevalsky provided detailed information on the life of the local population, the behavior of birds and animals, and the local climate, as well as geographical data.

Nikolay Przhevalsky before the fist trip. Photo cedit: shotguncollector.com

As a matter of fact, a comprehensive description of the region was produced. The expedition outcomes surpassed all expectations. Mr. Przhevalsky described them in The Journey to the Ussuri Krai in a vivid and insightful manner. It became clear that the star of the prominent Russian traveler had risen. That was the time when Nikolay Przhevalsky's fate was finally determined.

First Journey to Asia

Having returned to St. Petersburg, Mr. Przhevalsky started working on a new expedition. This time he aimed at countries that were almost completely unknown to Europeans. The Central Asian plateau covers a vast area of 4 million square miles, including Tibet, Mongolia, and historic Dzungaria, the northeastern part of present-day China. Huge deserts, steppes, and long mountain ranges are found here. There are the headwaters of China's great rivers, the Yellow River or Huang He and the Yangtze. The information about this vast territory available from Chinese sources was incomplete and contradictory at the time.

It was this area that the Russian traveler sought to explore. The government and the Geographic Society welcomed his initiative.

In 1870, Mr. Przhevalsky was assigned by the supreme command to Northern Tibet and Mongolia for three years. The expedition set out from Khyagt (Buryatia) on November 17.

Nikolay Przewalsky intended to make it to Beijing and explore the eastern part of the vast Gobi Desert along the way. After Beijing, the expedition headed north into the salt-saturated steppes with bad water where it explored Hulun Lake in southeastern Mongolia.

Locals suspected that the travelers were spies, so they treated them with hostility. Travelers were refused overnight stays and were not sold any food supplies. However, everything "worked according to plan" when compared to Nikolay Przewalski's later adventures when the expedition had to engage in real battles with gangs of robbers.

Having returned from the trip to the north, the travellers rested for a few days in the town of Kalgan and then set off to the west. They explored the Suma-Khada and Yin Shan mountain ranges for the first time. Most of the route followed the southern outskirts of the Gobi where no Europeans had ever been before. They crossed the Yellow River (Huang He) near Bautu and surveyed its course for more than 249 miles. Then they explored the deserts of Ordos and Alashan (all in a dangerous area devastated area because of the Dungan Revolt), the large salty Qinghai Lake, and reached Northern Tibet. There travelers were amazed by the huge herds of yaks, wild donkeys, antelope, and mountain sheep there. Having reached the upstream of the Yangtze (Blue River), they decided to go back.

The travelers were exposed to heat, sandstorms, and lack of water in the deserts. They were plagued by frost and thin air in Tibet. Thieves stole their camels on the way back. They had not been able to wash for weeks, and their clothes had turned to rags. Nevertheless, all hardships were overcome.

Over the course of three years, the expedition covered 6,835 miles and gathered rich collections of plants and animals as well as detailed meteorological data.

It was a triumph. Honors came one after another. The government awarded Nikolay Przhevalsky a generous allowance. He was elected a corresponding member of the Berlin Geographical Society. The International Geographical Congress in Paris sent him a letter of commendation. He got a gold medal from the Paris Geographical Society and the Constantine Medal from the Russian Geographical Society.

The outcomes of the expedition were processed for another three years after its return. In 1875, the first volume of Mongolia and the Tangut Countries was released. It was immediately translated into French, German, and English.

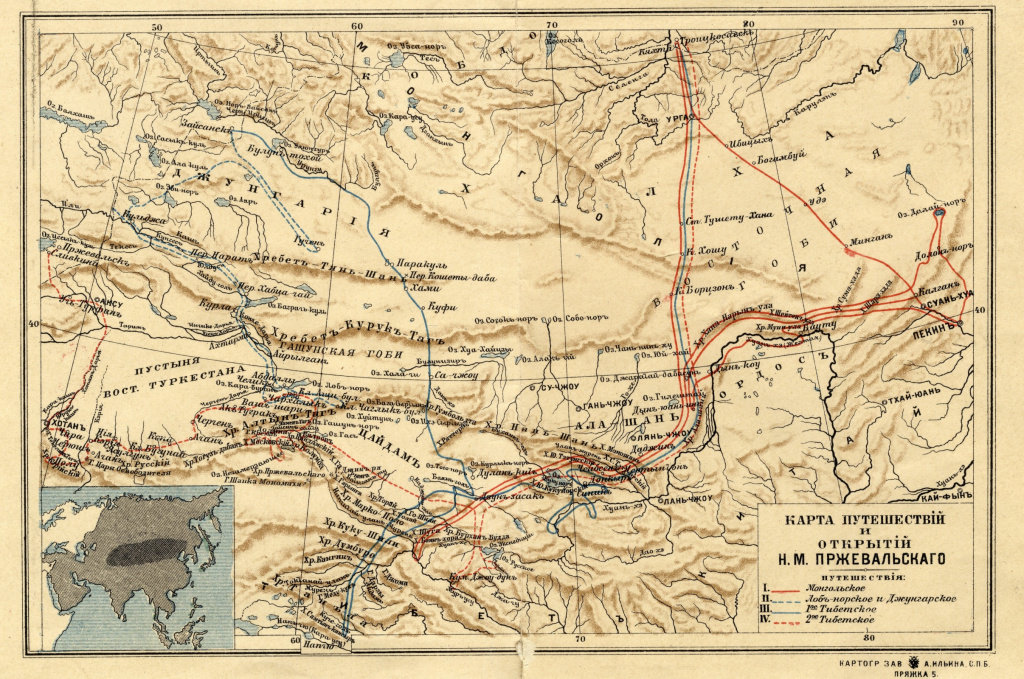

Nikolay Przewalski's research routes in Central Asia. Photo credit: wikipedia.org

Expedition to Lop Nur Lake

The next adventure was an expedition to the mysterious Lop Nur Lake known since the time of Marco Polo. It was located in Dzungaria (the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region of China). It was planned to travel from here to Northern Tibet, reach Lhasa, and further to the headwaters of the Irrawaddy and Brahmaputra Rivers.

The expedition left Kuldja and went along the valley of the Ile River in August 1876.

The exploration of Lop Nur Lake (currently dried up) with its tributaries was one of the most important tasks for Mr. Przhevalsky since the available information about it had been absolutely illusory. Having traveled around the lake in a boat and mapped it, Nikolay Przhevalsky traveled back. It was impossible to continue traveling because of the explorer's illness. Nevertheless, Mr. Przhevalsky was celebrated by the whole scientific community even for those discoveries. The Imperial Academy of Sciences elected him its honorary member.

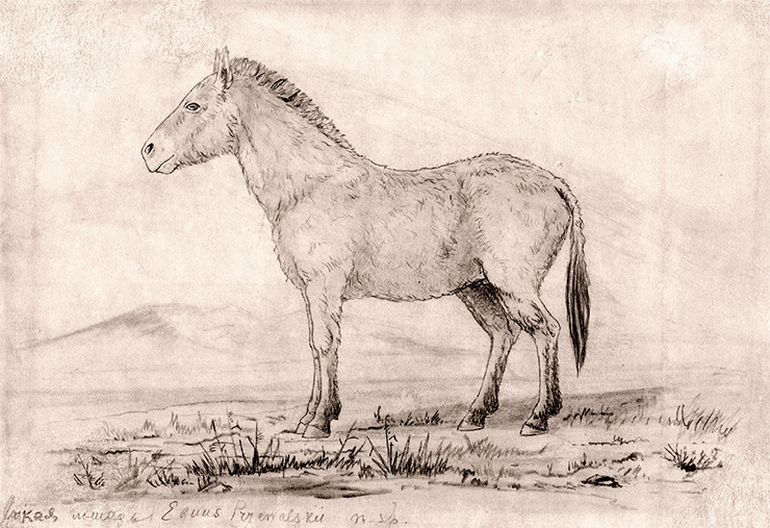

Przewalski's Horse by Vsevolod Roborovsky, a participant in Nikolay Przhevalsky's expedition. Photo credit: scfh.ru

To Tibet

On March 28, 1879, Nikolay Przhevalsky's team set off again on an expedition, this time to Tibet. The route went through the waterless steppe to the oasis of Hami Desert known since ancient times.

Once again in Tibet, the Russians were distressed by the lack of guides, the thin air and drastic fluctuations in temperature, and the sandstorms. On top of that, they had to fight real battles due to the outlaw attacks of the Tanguts and Yegrai. Once again, the travelers were delighted by the incredible abundance of wild animals. "It seemed as if we had entered a prehistoric paradise where humans and animals knew no evil or sin yet," wrote Nikolay Przhevalsky.

However, the closer they got to Lhasa, the forbidden city, the more hostile the local population became. Then the travelers had to turn back because the Tibetan government had expressly forbidden their entry. It was a mere 155 miles away from Lhasa.

The way back was even more difficult - people and animals were weakened, and food supplies were depleted.

In general, Nikolay Przhevalsky used to avoid the secular fuss. Having returned from the expedition, he wished for solitude more than anything else. He found a real godforsaken spot in Smolensk Governorate where he bought the Sloboda estate. It was a true paradise for a passionate hunter and fisherman with hundreds of miles of forests, two lakes, and two rivers nearby. Here, in solitude, he worked on books, summarizing his expedition experience.

"Time and again, while sitting in a buttoned-up uniform in the salon of a nobleman, I reflected with regret on my free life with my fellow officers and Cossacks in the wilderness. Compressed tea and mutton were drunk and eaten with greater appetite there than the foreign wines and French dishes here. There was freedom, and there is gold-plated prison here; everything is in due form, according to the standards here. There is no simplicity, no freedom, no air...," Nikolay Przhevalsky wrote with sadness.

Last Expedition: to the Headwaters of the Yellow River

On October 20, 1883, Nikolay Przhevalsky's expedition set out from Khyagt. He once again aimed for the upper reaches of the Huang He River.

There were again troubles with the local population and guides. Mr. Przhevalsky solved these problems with his personal determination. After the local ruling prince of Tibet, Dzun-Zasan, refused to sell camels and rams to travelers and to provide them with a guide, Mr. Przhevalsky acted firmly. "At that time, without any further argument, I placed Dzun-Zasan under arrest in our camp tent. Then, an armed guard was assigned to stay near the tent. The prince's helper, perhaps an even greater rascal, was chained outside, and one of his associates who dared to strike our interpreter, Abdullah, was immediately whipped. These measures produced the intended effect," wrote the traveler. Everything required was immediately delivered.

The expedition reached the headwaters of the Huang He River and "drank water from its headwaters”. They explored the headwaters of the river, the surrounding mountains, as well as the divide of the Yellow and Blue Rivers, and the upper reaches of the latter.

On October 29, 1886, the expedition reached the Russian border and headed to the town of Karakol (now Przhevalsk).

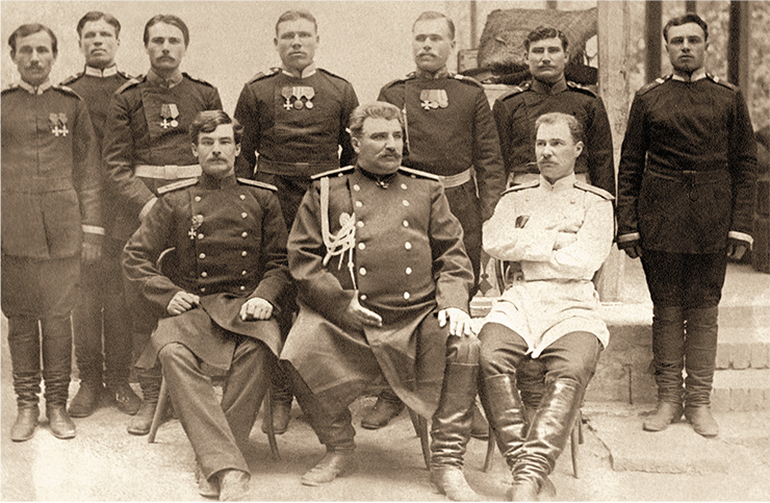

Participants of the Second Expedition to Tibet (1883–1885). Nikolay Przhevalsky is in the center. Photo credit: scfh.ru

Fifth Journey to Asia. Death

Having processed the materials of his last journey, Nikolay Przhevalsky thought of a new one. This time he intended to travel to Tibet via Eastern Turkestan via the shortest route.

This expedition caused concern not only in the Chinese government, which was very reluctant to issue Nikolay Przhevalsky a passport but also in England where they suspected that his expedition was a secret political mission of the Russian Government. Nevertheless, Mr. Przhevalsky's plan had no chance to come true as the traveler passed away on the way.

Nikolay Przhevalsky died at 49. He was still full of vigor, and his death was sadly absurd. While swimming in the Kara-Balta River (Kyrgyzstan), he accidentally took a sip of water in spite of his own strict prohibitions and contracted typhoid fever.

The great traveler was buried on the shore of Issyk-Kul Lake. His grave is in the settlement of Pristan'-Przheval'sk near the town of Karakol (Przhevalsk).

Nikolay Przhevalsky monument at his tomb in Pristan'-Przheval'sk. Photo credit: M. Kolodin/wikipedia.org

What was the Secret of Nikolay Przewalsky's Success?

It was first of all about organization and discipline. He picked all his companions from the military staff, and his units had cast-iron discipline. At the same time, he had the ability to inspire loyalty and genuine diligence in them. And his letters to his companions were filled with almost parental affection.

Nikolay Przhevalsky did not lose a single person in his challenging and dangerous crusades despite a lot of extremely dangerous situations, which was a record of his own.

Nikolay Przhevalsky evaluated the challenges ahead with a cool mind and always acted with determination, even harshness. "Three guides are necessary for the success of a long-range and risky journey to Asia," he wrote, "you need money, a rifle, and a horsewhip."

"He is worth a dozen educational institutions and hundreds of good books."

What did Nikolay Przhevalsky do for science? A total of more than nine years he spent in the most difficult environment in the heart of Central Asia, having traveled more than 18,640 miles in the course of his expeditions.

His geographical, as well as zoological, studies are equally important for biology.

He described many new species and interesting local forms. He systematized data, observed, and described the behaviour of animals. He wrote about research on the wild camel, yak, Przewalski's horse (an intermediate species between horse and donkey), and the Tibetan brown bear. And that's not to mention new species of antelope, wild sheep, birds, fish, insects, etc.

Nikolay Przhevalsky collected about 1,700 plant species. In fact, his efforts revealed the flora of Tibet and Mongolia to science.

Mr. Przhevalsky's expeditions revolutionized our knowledge of geography, nature, and climate in Central Asia.

"David Livingstone and Henry M. Stanley," wrote Joseph Dalton Hooker, "were brave pioneers but only succeeded in plotting the routes they had traveled on the map. They did nothing to explore nature. It was even necessary to send another traveler after the distinguished Mr. Barth to plot his routes on the map. Only Nikolay Przhevalsky combined the personality of the most courageous traveler with a geographer and naturalist".

Having received the news of Nikolay Przhevalsky's death, the Novoe Vremya published an obituary that was supposedly authored by Anton Chekhov. It says that the deceased "is worth a dozen educational institutions and hundreds of good books.”

New publications

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.  Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.

Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.  When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.  Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."

Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."  "Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...

"Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...