Proud of Our People! Kazimir Malevich and his Black Square

/ Главная / Russkiy Mir Foundation / Publications / Proud of Our People! Kazimir Malevich and his Black SquareProud of Our People! Kazimir Malevich and his Black Square

Anna Efremova

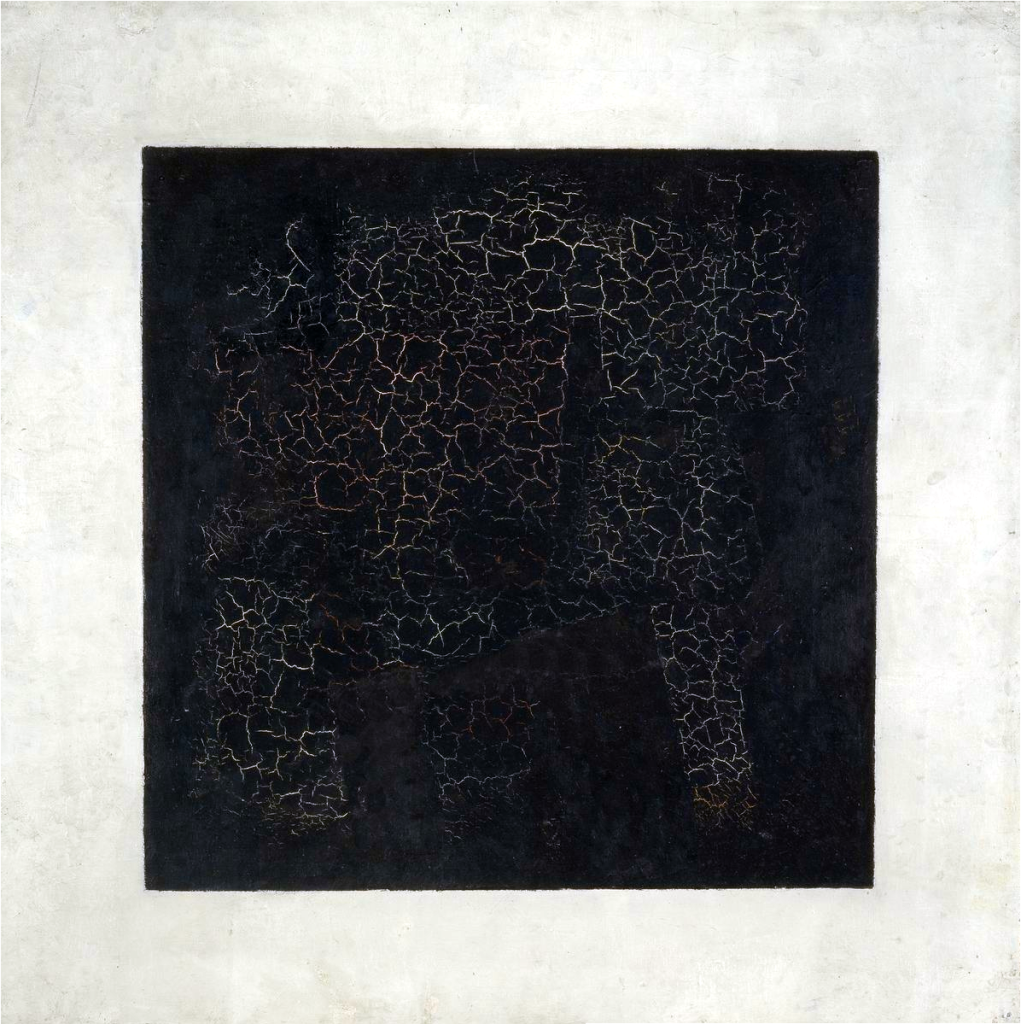

If Malevich's Black Square is not the most famous work of art in the world, it is certainly the most discussed one. The artist did not see Black Square as an ordinary painting. He regarded it as a manifesto and beyond, "I have transformed into zero of forms and moved beyond zero to non-objective art." His contemporaries perceived this work as an attempt to create not just a new art but a new religion.

He studied drawing from peasant paintings

Kazimir Malevich is one of the most well-known and expensive abstractionist artists in the world of art. He was the founder of Suprematism (he was the one who came up with this term), and a philosopher. He wrote "On New Systems in Art" and his key work "Suprematism. The World as Non-Objectivity or Eternal Peace". However, he never had any special education. He made four attempts to join the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture. None of them was successful due to a lack of formal knowledge. Yet, he had chosen his way as an artist back in his childhood when he and his parents used to move from one village to another. That time was described in his "Autobiography" as follows, "The circumstances that surrounded my childhood life were such that my father worked in the sugar beet plants, which are usually built in the middle of nowhere, well away from towns and cities. The sugar beet plantations were huge. A large workforce, mostly peasants, was needed to cultivate these plantations. Young and old peasants worked on the plantations throughout most of the summer and fall, while I, the artist-to-be, enjoyed watching the fields and the colorful workers who weeded and thinned out the beets.

Squads of girls in colorful clothes were moving in rows all over the field. It was warfare. Troops in colorful dresses were fighting weeds, freeing the beets from being overgrown with unwanted plants. I enjoyed looking at those fields in the morning when the sun was still low. The skylarks were singing in the air and the storks were jugging and flying to catch frogs. Kites were circling in the air looking for birds and mice.”

At that time, Kazimir had already a clear understanding that he would not work in a factory like his father, "I thought, 'Why would my father want to get up at night when everyone is asleep, and go to work, or go to bed when everything enjoys life and breathes in the air of fields, meadows, forests, and orchards...'"

There was also another important reason why Malevich felt much closer to the peasants than to the factory workers. It was the drawing.

"As I mentioned above, the village was practicing art (a word I didn't know at the time). To be more accurate, it was doing things that I liked a lot. Those things were the secret of my sympathy for the peasants. I watched with great excitement how the peasants painted and helped them to spread clay on the floors of the hut and make patterns on the stove. The peasant women were great at drawing roosters, horses, and flowers. Paints were all made on-site from different clays and blue. I tried to practice this culture on the stoves in my house but nothing worked. They used to say that I made the stoves dirty. Thus, fences, barn walls, etc. were used.”

The boy went with his father to a fair in Kiev. It was a memorable event of his childhood as he saw real paintings for the first time. He intuitively sensed the difference between primitive paintings in the countryside and urban art. There was one painting in the store that made a profound impression on him, "The painting that captivated me was of a girl sitting on a bench and peeling potatoes. I was astonished by the realism of the potatoes and peels on the bench next to the excellently painted pot. That painting was a revelation to me, and I remember it to this day.”

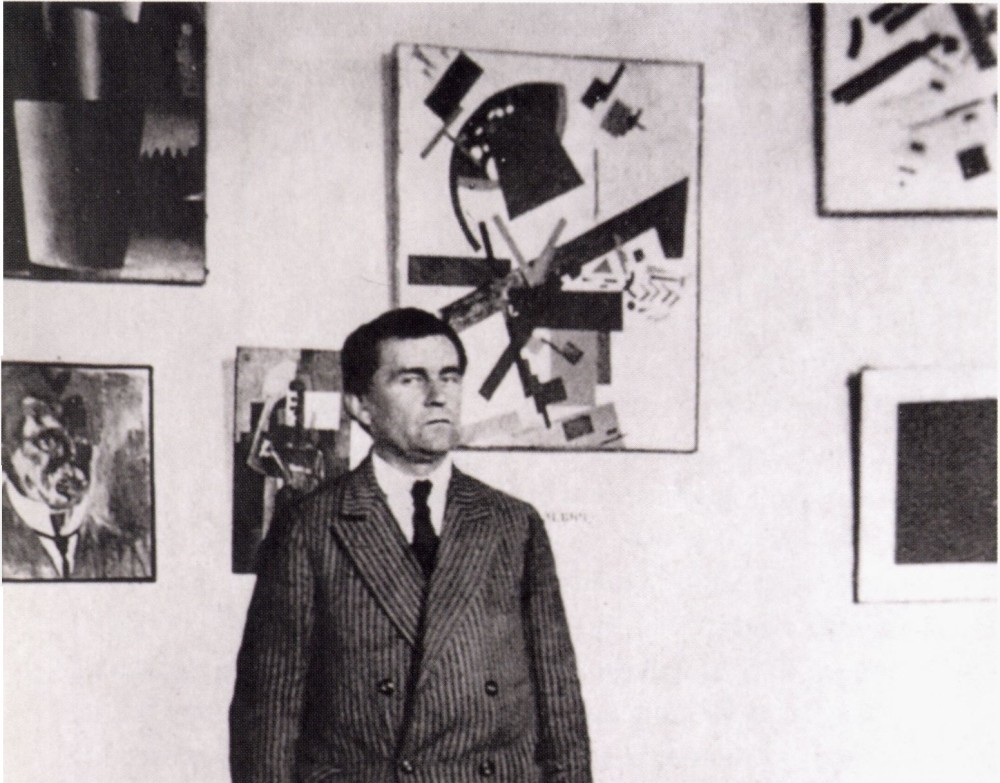

Kazimir Malevich in Kursk. Around 1900. Photo credit: k-malevich.ru

Cubists, Impressionists, Futurists, Fauvists…

No wonder that during the early period of his painting career, Kazimir Malevich was a follower of the realist painters, such as Ivan Shishkin and Ilya Repin. However, when he again failed to join the School of Arts and ended up in the artists' commune in Lefortovo, Malevich's views underwent dramatic changes. He buddied up with the futurists, walked around Kuznetsky Most with wooden spoons in his buttonholes, and referred to his recent idol, Ilya Repin, rather disdainfully, "The BrandMeister of dumb firemen who suppress the fire of everything new."

The first attempt to settle in Moscow was a failure for Kazimir Malevich as he had no money. He returned to Kursk where the painter's first wife and two children, as well as his parents, lived at that time. He came back to Moscow in 1905 and got straight to the epicenter of the raging revolution. Kazimir Malevich met with professional revolutionaries and even participated in the battles for Krasnaya Presnya, as his memoirs show.

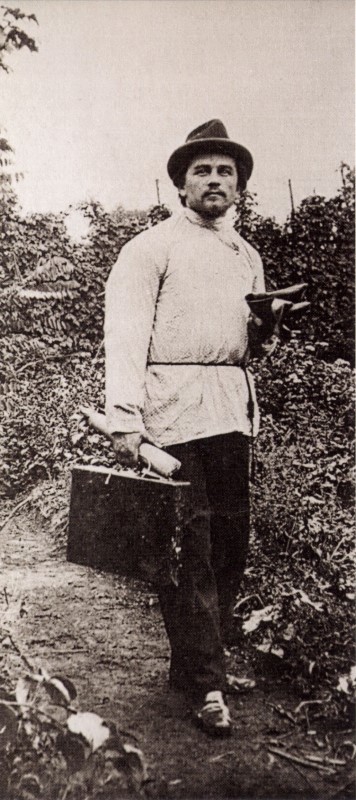

Photo credit: bessmertnybarak.ru

It was only in 1907 that he finally managed to relocate to Moscow and started attending the studio school of the painter Fedor Rerberg. Kazimir Malevich learned the painting techniques there. He also studied the history of fine art. He spent a lot of time in the Tretyakov Gallery studying the exhibited paintings. He also did not miss any of the contemporary art exhibitions.

Painters used to actively explore new forms of artistic freedom during those pre-revolutionary and pre-war years, which would become the forerunner of the epoch shift. Kazimir Malevich also tried to follow Cubists, Impressionists, Futurists, and Fauvists. He gained some experience in each case. For instance, Kazimir Malevich said that impressionism had helped him to escape figural thinking and taught him to treat reality as something that "should be transformed into the perfect form generated in the depths of aesthetics.”

In 1910, he took part in the first exhibition of Knave of Diamonds, a major association of early avant-garde artists. The young painters were inspired by Vincent Van Gogh, Paul Gauguin, Paul Cézanne, and, surprisingly enough, ancient Russian icons. The latter were actively restored and presented to the public in their original and colorful form.

Kazimir Malevich wrote that the paintings at the Knave of Diamonds exhibition were like multi-colored flames. And it was the first time when he looked at Russian icons very differently, "I felt something dear and wonderful in them. They featured the entire Russian culture with its emotional art. Then I remembered my childhood, horses, roosters..."

From Victory Over the Sun to Black Square

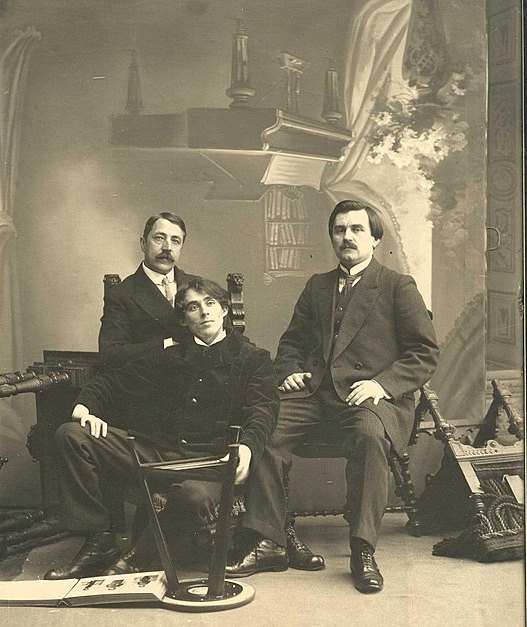

Alogical Portrait of the Futurists M. Matyushin, A. Kruchenykh, and K. Malevich, 1913. Photo credit: wikipedia.org

In 1913, the Luna Park Theater in St. Petersburg hosted a performance of Victory Over the Sun, a futuristic opera. It described how the "Budetlyans", a group of people of the future, set out to conquer the sun. One of the opera's authors described its underlying meaning, "The opera has a profound depth. It mocks the old romanticism and verbalism. The whole victory over the sun is a victory over the old customary concept of the sun as the beauty." The authors' idea was that the future can only be built after the past has been destroyed.

Victory Over the Sun. The 2013 production with costumes based on Kazimir Malevich's sketches. Photo credit: Shakko. / wikipedia.org

Kazimir Malevich became the production designer of the opera. The black square was used in the opera set for the first time. It replaced the solar circle as a symbol of the victory of active human art over passive nature. It looks as if the action takes place inside a cube of some kind. The intensity builds up through the set changes: spirals, lines, and abstract figures obscure the sun more and more with each new scene. The culmination is the black square replacing the sun. It is the symbol of the new world.

"Zero of Forms"

Kazimir Malevich's most famous painting was displayed in the 0.10 exhibition in 1915. Zero was a symbol reflected in the title of the exhibition and the key to its understanding. Kazimir Malevich declared the square to be "zero of forms", "I have transformed into zero of forms and moved beyond zero to non-objective art." The artist's Black Square became a synonym for the Absolute where everything originates and where everything eventually disappears. And the painting was placed in the red corner of the exhibition where icons are usually displayed.

Black Suprematist Square, 1915. Photo credit: wikipedia.org

Many contemporaries, in particular Alexandre Benois, the founding member of the Mir Iskusstva (World of Art) Association, saw clear theomachist motifs in this painting. Kazimir Malevich wrote in the description of the exhibition, "When the mind abandons the habit to see natural places, Madonnas and shameless Venuses in paintings, then we will be able to see a pure artwork." Alexandre Benois understood it as an appeal for "the extinction of love, in other words, the warming element, without which we will inevitably get cold and perish." Alexandre Benois insightfully prophesied that "Black Square with its white rim will bring everyone to destruction through arrogance, hubris, and trampling upon everything that is about love and tenderness." Well, we should admit that the painter felt the upcoming destruction of the old world and expressed it in a more than convincing way.

From that time on, Kazimir Malevich became the artist of one painting, regardless of the multitude of other works. He became the founder of Suprematism (from the Latin supremus meaning supremacy). It feels as if Kazimir Malevich drew a final line with his Black Square, thus indicating that color was more important than form, and the color itself was unnecessary as everything was swallowed up by blackness.

Suprematist coffin for the artist

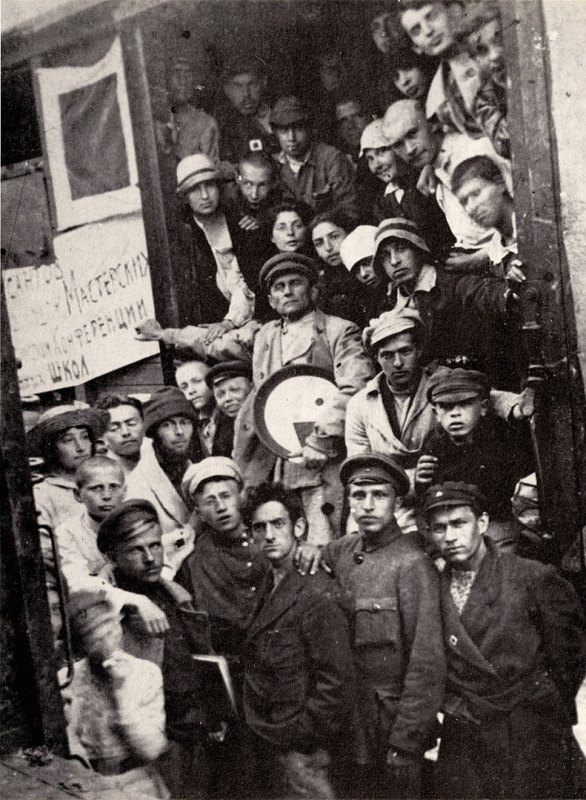

During the 1917 revolution times, the painter who advocated the destruction of the old forms of art fit in well. He headed the Artistic Department of the Mossovet, took part in educational activities, and worked out the project of the People's Academy of Arts. In 1920, he and his students in Vitebsk founded the MOLPOSNOVIS group (Young Followers of the New Art), which he soon renamed UNOVIS (The Champions of the New Art).

In 1927, he visited the opening of his exhibitions in Warsaw and Berlin. He was welcomed there as a prophet of the new times. In 1930, Kazimir Malevich was arrested but for a short time only. Yet, the perception of the avant-garde had irreversibly changed in the USSR by that time. Destroyers were no longer in demand. There was a need for creators, and hence socialist realism. Kazimir Malevich also turned back to realism. He started painting "Socialist City" in 1932. However, he was not able to finish it in time. He died of a serious illness in Leningrad in 1935.

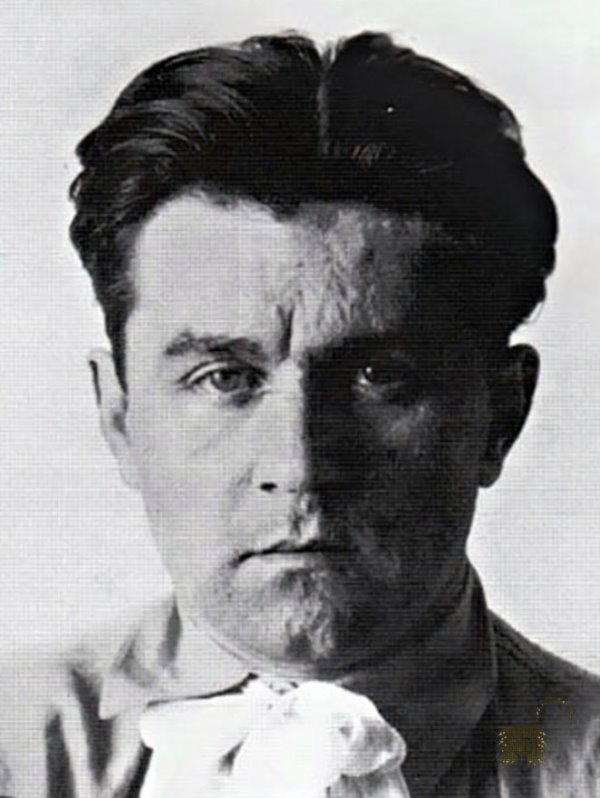

UNOVIS members, Kazimir Malevich is in the center. Photo credit: wikipedia.org

According to his will, Kazimir Malevich wanted to be buried in a cross-shaped suprematist coffin. The funeral planners opted for a more traditional form, however, the coffin was decorated in an appropriate way. There was a black square on the top and a red circle at the feet. Kazimir Malevich was cremated and his ashes were buried under the artist's favorite oak tree in the village of Nemchinovka, Moscow Region, where the painter spent a lot of time. The grave was lost during the war but volunteers managed to figure out its approximate location in 1988. They installed a concrete white cube with a red square on it there.

Funeral of Kazimir Malevich, 1935. Photo credit: The World Funeral Culture Museum

New publications

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.  Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.

Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.  When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.  Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."

Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."  "Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...

"Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...