Yuri Knorozov, Maya Language Decoder

/ Главная / Russkiy Mir Foundation / Publications / Yuri Knorozov, Maya Language DecoderYuri Knorozov, Maya Language Decoder

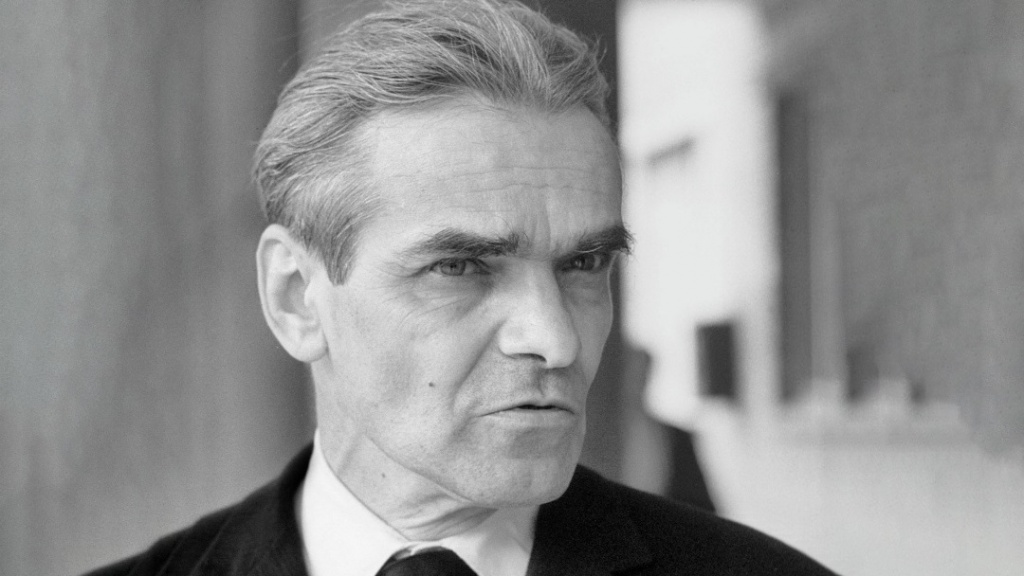

Yuri Knorozov. Photo credit: smotrim.ru

"What was created by one human mind can certainly be resolved by another," said Yuri Knorozov, a Russian scientist back in 1996 when Mexican television asked him how he had managed to decode the Mayan language. The Soviet scientist never visited Mexico. How he succeeded in accomplishing what the world's best experts had struggled with for so many years, is still a mystery.

Mysterious Mayan Codices

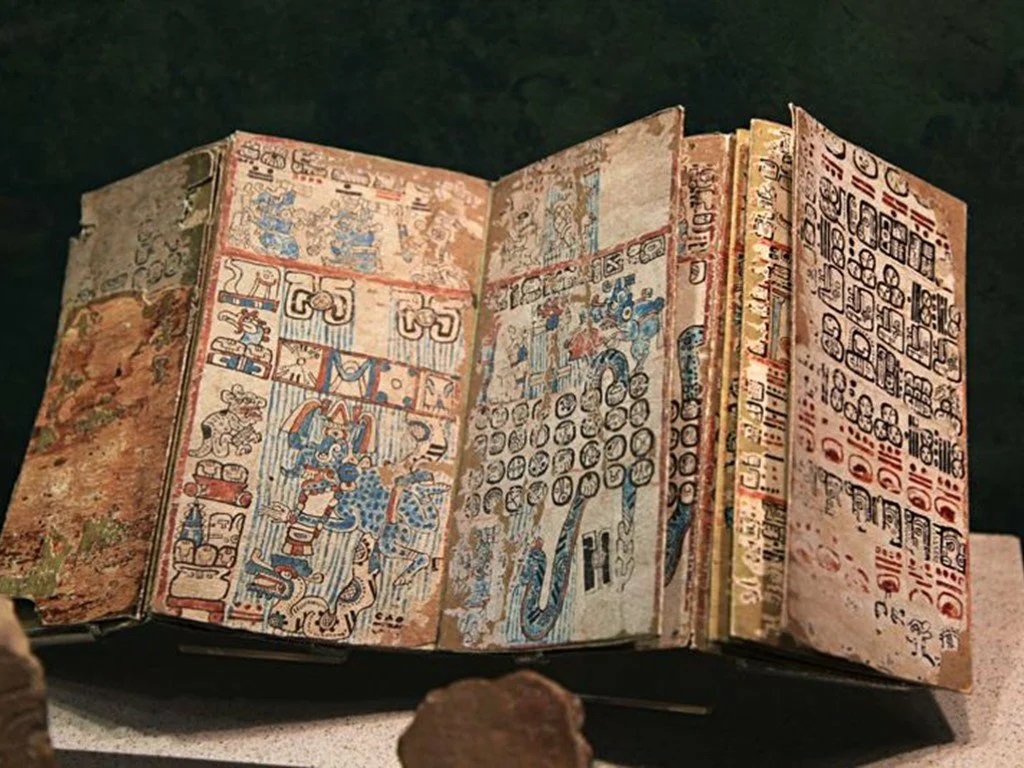

… Johann Goetze, a librarian at the Dresden library, purchased an ancient manuscript from an unknown person in Vienna in 1739. It was later found that the manuscript dated back to the 13th century and was made up of 39 sheets. The latter were covered with writing on both sides and glued together in the form of a squeezebox. It was also discovered that the paper was made of the leaves of a ficus tree. However, the content of the writings was a mystery to researchers for a long time.

The manuscript is known as the Dresden Codex based on its storing location. It is the earliest and most ancient specimen of Maya graphic records. By the way, this codex contains the Mayan calendar that is known probably to all inhabitants of the Earth. Its triumph time was at the end of 2012 when doomsday had been predicted according to this calendar. However, more accurate interpretations believed that it had referred only to the end of a major astronomical cycle.

So let us get back to the Dresden Codex. Alexander von Humboldt, a German naturalist, found the pages of the Dresden Codex in the Dresden Library and published them in 1810. At first, scholars could not identify its origin. They used to refer to it as Mexican or Aztec. However, in 1859, Léon de Rony, a French scholar exploring the pre-Columbian civilizations of the Americas, found a similar manuscript in the trash (!) at the Paris National Library. Then the situation became somewhat clearer.

Dresden Codex. Photo credit: mirtesen.ru

In 1969, the Madrid Codex was found. It was the third Mayan Codex after the Dresden and the Paris ones. It was purchased by Charles-Étienne Brasseur de Bourbourg, one of the founders of science-based Maya Studies. He spent 15 years as a missionary in Mexico and Central America and collected a wealth of field material on the history of pre-Columbian Indian civilizations.

Discovering the written sources of the ancient civilization became a sensation. So, the middle of the nineteenth century saw a lot of enthusiasts rushing off to South America to search for traces of the Maya. Their efforts resulted in the discovery of ancient monuments and sketches of them. Having compared the Dresden Codex and those sketches, the scientists realized that there was the same character system as the ancient Maya had. How to read it all?

Maya script at the Palenque Site Museum, Mexico. Photo credit: wikipedia.org

"This work will constitute the glory of Soviet science."

One of the world's leading experts on Maya civilization, the English ethnographer and archaeologist Eric Thomson, made an attempt to decode the Maya language. He suggested that Maya script was of a pictographic type, and its signs should be understood according to the characters they represented within the relevant context. He disbelieved the phonetic feature of glyphs. For a long time, he was convinced that the discovered texts were purely religious. This perspective was accepted in the 1930s and 1940s until an article with the modest title "Ancient scripts of Central America" was published in the Soviet Ethnography magazine in 1952. It was followed by an explosion in the world scientific community…

Lord Thomson's fury was indescribable as the discovery had been made literally by a boy (Knorozov was 30 years old, while Thomson was 54), furthermore, from the ideological opponent's camp! He viewed those findings as a personal insult and confronted Knorozov right away. However, he resorted to Cold War methods rather than scientific arguments. In his personal opinion, Soviet scientists were incapable of accomplishing anything because they "use the method of Marxist historiography." Sergei Tokarev, the head of the Institute of Ethnography of the USSR Academy of Sciences, provided a reference to Yuri Knorozov for his postgraduate studies in 1950. Interestingly, he wrote the following prescient words: "This work, when completed, will constitute the glory of Soviet science and will starkly illustrate its superiority over its foreign bourgeois counterpart even in such an area as the studies of ancient American scripts that have kept the best American specialists working on for decades." And it turned out that he was right!

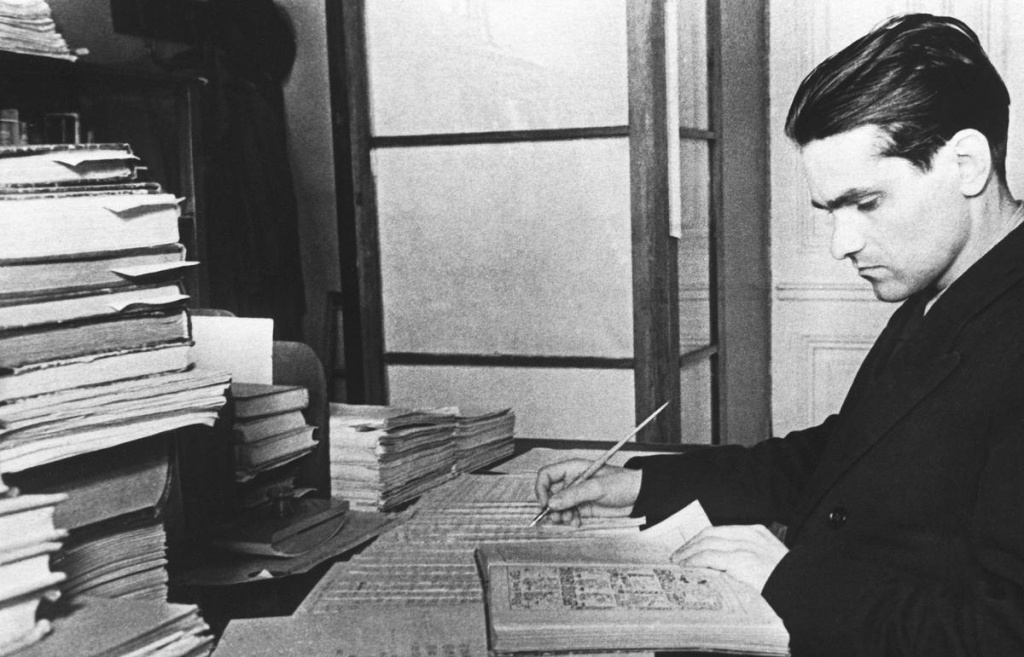

Yuri Knorozov at work. Photo credit: scientificrussia.ru

Nevertheless, there were quite a few other scientists, including renowned ones, who were courageous enough to join Knorozov's supporters. Those dominant names included Michael D. Coe, the famous American archaeologist, and Professor at Yale University. So, who was that young Soviet scientist that brilliantly resolved a seemingly unresolvable theorem in the field of Ethnography, that is, decoded the Maya script?

Also known as Sinukhet

Yuri Knorozov (by the way, his surname is very rare) was born in a small settlement near Kharkov on November 19, 1922. His father worked for an insurance company. After the Revolution of 1917, he headed a department in the Southern Railway Administration. An interesting fact is that even before his parents got married, they had decided to raise their future children up following Vladimir Bekhterev, the famous Russian psychiatrist and neuropathologist. For instance, his father wanted all five children to develop the simultaneous function of both hands so that they had no dominant hands, and all actions could be performed with either right or left hand with the same efficiency. Perhaps, the intention was to stimulate both hemispheres of the brain for their harmonious development. However, this approach eventually resulted in the reserved nature and withdraw behavior of all the children in the family.

Initially, Yuri made plans to become a psychiatrist (that was Bekhterev's effect) and joined the Workers' School at the Medical Institute in Kharkov. However, having finished the Workers' School, he changed his mind and enrolled in the Department of History. That was when he got interested in shamanistic practices and then in Egyptian hieroglyphics.

During the war, he was condemned as unserviceable. In 1943 his father was reassigned to work in Moscow and managed to bring along his wife and son Yuri. Yuri was admitted as a second-year student of the History Department of Moscow State University. He also studied Egyptology. His fellow students even nicknamed him "Sinukhet" (being inspired by The Story of Sinuhe, an ancient Egyptian story). Still, in 1944 he was called up for military service, where he served as a telephone operator. And after the war ended, Yuri Knorozov resumed his third year of studies.

One of his associates at the time recalled that back in 1946 Yuri Knorozov had already declared that his dream was to decode Mayan scripts. His intention was inspired by two books that the history student Yuri Knorozov had a chance to read in the Lenin Library, namely The Maya: Diego de Landa's Account of the Affairs of Yucatán by Diego de Landa (there was a microfilm of the first edition in the library collections) and The Maya Codices published in Guatemala in 1930.

Following his thesis statement on the research of the Xorazm Vohasi, Yuri Knorozov told his academic advisor that he was interested in Mexico only. He had already started translating The Maya: Diego de Landa's Account of the Affairs of Yucatán from Old Spanish. This extremely important book for researchers was written by the bishop of Yucatan in the middle of the 16th century. He earned "fame" for burning almost all Mayan manuscripts and destroying many of their monuments. Nevertheless, he also left valuable information about the Mayan civilization, including a list of correspondences between Mayan glyphs and Spanish letters.

Image of a page from The Maya: Diego de Landa's Account of the Affairs of Yucatán where de Landa describes the Mayan alphabet. Photo credit: wikipedia.org

The bishop, of course, was unaware of the fact that the Maya script was not alphabetic but rather logosyllabic where some symbols represent certain words, while others represent syllables. There are about a hundred syllabic symbols in Maya script, and over a thousand symbols representing words are known. Nevertheless, 27 glyphs in the "de Landa's alphabet" were of great importance to science and the further decoding of the Maya script.

Codebreaker

Yuri Knorozov moved from Moscow to Leningrad to join postgraduate studies at the Institute of Ethnography of the USSR Academy of Sciences. However, he was not admitted at first. Then he got a job as a Junior Research Associate in the Department of Central Asia at the Museum of Ethnography of the USSR Peoples. According to reports, all the walls in the small room where he lived were covered with drawings of Mayan glyphs, and almost all the space was packed with books.

Regardless of all the efforts undertaken by his senior academic colleagues, Knorozov was never admitted for postgraduate studies (the official version stated that he was refused because he had lived in the occupied territories during WW2). Yet, he managed to implement his biggest dream, which is to decode the Maya script. A year after the publication of the article in Soviet Ethnography, it was published as a separate monograph in Spanish in Mexico. That was how Yuri Knorozov's precedence in such a major discovery was secured.

Yuri Knorozov with his beloved Asya the cat. Photo credit: wikipedia.org

The scientist developed the so-called cross-reading, i.e. his decoding method for glyphs. Suppose one combination of symbols can be understood in a certain way, then another sequence featuring the known combination makes it possible to figure out the meaning of a new symbol. He created a comprehensive catalog with symbols identified by him. Each of such symbols corresponds to a certain phonetic value. Later on, Yuri Knorozov's method was used to decode Easter Island writing and Proto-Indian inscriptions. His scientific work became the basis for his academic dissertation. Furthermore, Knorozov was awarded a doctorate without the previous stages because of his significant contribution to science.

The subject of his academic dissertation also became a sensation in the scientific and cultural community of the Soviet Union. In 1963, Yuri Knorozov published Maya Script, a magnificent book revealing the principles of decoding. He was awarded the 1977 USSR State Prize for this work.

The ingenious scholar continued to work with Mayan texts throughout his life. However, he was only able to see them for real in 1990. That time he visited Guatemala where he was honored with the Grand Gold Medal. In 1995, he was awarded for outstanding service to Mexico the Silver Order of the Aztec Eagle. In March 2018, a monument to the famous Russian scientist was erected in the Mexican city of Merida to commemorate his invaluable contribution to the decoding of scripts of the ancient civilization. The monument stands next to the large Mayan World Museum of Mérida.

Well, the Mayan texts are still very actively researched today, and the excavations continue to reveal new monuments with glyphs to the world. The world of the Maya uncovered by Yuri Knorozov still holds a lot of mysteries.

New publications

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.  Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.

Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.  When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.  Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."

Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."  "Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...

"Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...