Not COVID-19 only: History of epidemic control in Russia

/ Главная / Russkiy Mir Foundation / Publications / Not COVID-19 only: History of epidemic control in RussiaNot COVID-19 only: History of epidemic control in Russia

Alla Shelyapina

Photo credit: Denis Grishkin / Press Service of the Mayor and the Moscow Government/ mos.ru (CC BY 4.0)

The history of medical vaccination dates back to about 250 years ago. Infectious diseases caused the deaths of millions of ordinary people and even kings and emperors. For example, the young Russian Emperor Paul II left the throne due to an agonizing fever caused by black smallpox in 1730; French King Louis XV died of smallpox in 1774. When vaccination against smallpox was introduced in Europe, Russia became one of the first states that encouraged vaccination.

Smallpox Vaccination in Russia

As the German proverb runs, “Few have escaped smallpox and love.”

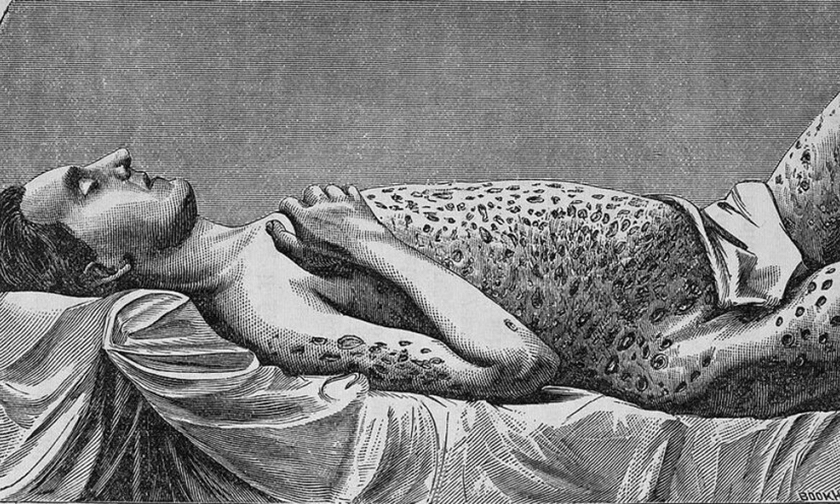

The history of global vaccination began with the battle against smallpox. In order to realize the scale of this disease spread in Russia, you can literally trace it by such surnames as Ryabykh or Ryabtsev*, Shchedrin** that were very common in the country. In the 18th century, about 150,000 to 200,000 people died from smallpox in the Russian Empire per year. The mortality rate was 40 to 50% of those affected.

Just like many other things, vaccination technology was brought to Europe from the East, namely the Ottoman Empire. They started vaccinating girls in the sultan's harem and then proceeded to children and adults all over the country.

The English medical scientist Thomas Dimsdale was the one who introduced this method in Russia.

Thomas Dimsdale had the reputation of an experienced inoculator (inoculation means the artificial introduction of infection). On October 12 (October 23 N.S.), 1768, he inoculated Catherine the Great and the heir to the throne, the next Emperor Paul I. Almost all dignified grand seigneurs, including the Orlov brothers, Razumovsky, and Potemkin, were also inoculated.

More stories: Vaccination for the EmpressIn fact, Catherine the Great described Louis XV's death in 1774 as barbaric since Europe had already been well aware of how to prevent smallpox by that time. Unlike the courageous Russian empress, the French king was afraid to be inoculated and died before his time having been infected by his young mistress. Moreover, a special decree prohibited smallpox inoculation in France until 1762! At the same time, when Catherine the Great ascended the throne in 1762, one of her first decrees was "On the establishment of special town houses for those affected by dangerous and catching diseases, and the appointment of doctors for that purpose". The establishment of "smallpox houses" was commenced in the largest towns of the empire. At the core, they were children's infectious disease hospitals.

After Catherine and her son were vaccinated, Count Aleksey Arakcheyev initiated inoculations for his peasants. He was the first to arrange the process in his estates on a centralized basis. Then feldsher's stations were gradually set all over the country.

The work initiated by Thomas Dimsdale in Petersburg was continued by Thomas Holiday, his compatriot. Thomas Dimsdale has become the first doctor of the Smallpox (Smallpox Vaccination) House in Petersburg. All comers were vaccinated free of charge and were rewarded with a silver ruble featuring a portrait of Empress Catherine the Great. Holiday lived in Petersburg for a long time. He got rich, bought a house on the English Embankment, and was granted a plot of land on one of the islands in the Neva delta. Allegedly, the island was named after him, although his name was changed into "Goloday", the word that was easier to understand for Russians (now Decembrists' Island).

The medal "In memory of the introduction of smallpox vaccination in Russia", October 12, 1768. Photo credit: Istorik.RF

Edward Jenner, also an Englishman, was the first to use the term "vaccine", as well as the modern vaccination method. This method has been used in Russia since 1801.

Nevertheless, such vaccinations did not become mass-scale in Russia right away. Ridiculous rumours about the horrible consequences of vaccination began to circulate. According to some of them, all vaccinated British people got cow horns growing because the material for the vaccine was taken from cows and calves that had recovered. Governors across the country received reports from doctors' offices that many priests put parents off this procedure. It came to a point where the Synod under the direction of the Chief Procurator had to intervene and oblige priests and bishops to promote smallpox vaccination.

By 1811, 11% of all newborns were vaccinated against smallpox throughout the Russian Empire, from Vilna to Alaska. However, Old Believers considered smallpox vaccination to be "the seal of the Antichrist" until the beginning of the 20th century. So the followers of the " Old Faith" refused to vaccinate themselves and their children.

Smallpox patient. Photo credit: Pravmir.ru

The Smallpox Eradication Programme was proposed by the USSR delegation at the XI Assembly of the World Health Organization in 1958. It is through this program that smallpox was defeated in the world by 1980. Since 1982, the USSR ceased to vaccinate against it as the disease was completely eradicated.

No prophet is accepted in his own country. Vaccines by Waldemar Haffkine

Once Russian writer Anton Chekhov wrote to his friend about Waldemar Haffkine: "He is the least known person in Russia, while he has long been referred to as the great philanthropist in England."

Few people know that the first effective vaccine against cholera was invented by Waldemar Haffkine, a scientist and physician from Odessa, in 1892. Back then, he was working at the Pasteur Institute in Paris. His vaccine in its improved version saves people to this day. Later on, in 1896, the scientist developed a vaccine against the bubonic plague known as the black death that had been killing people for centuries.

The appointed Companion of the Order of the Indian Empire was born in Odessa. He studied at Novorossiysk University and was Ilya Mechnikov’s favorite student. Haffkine was also a political emigrant and member of 'People's Will' (revolutionary political organization in the Russian Empire), which might be the reason he was not renowned in his homeland.

Most of the plague and cholera epidemics broke out in India. It is no coincidence that the Haffkine Institute, one of India's largest scientific institutions, is located right there, in Mumbai. After all, it was Haffkine who saved millions of Indians with his vaccine during the 1896-1897 plague epidemic.

Waldemar Haffkine. Photo credit: ru.wikipedia.org

However, his recognition as a scientist postdated his discoveries. Governments of Russia, France, and Germany refused to use his vaccines. Furthermore, some European bacteriologists doubted the benefits of vaccination. Robert Koch who had discovered the causative agent of tuberculosis remarked that immunization was "too good to be true.” It took some time before the United Kingdom agreed to use Haffkine's vaccines in India where millions of people were killed by plague and cholera epidemics.

The scientist received much-anticipated recognition after his work in India in the late 19th - early 20th centuries. He was the guest of honor at royal receptions. The French Academy of Sciences honored him with an award. Russian physicians and scientists adopted the practices that he had used in India. Waldemar Haffkine returned to Great Britain in 1915. At that time, he arranged vaccinations for soldiers going up the line of World War I. He spent the last 15 years of his life in Paris, where he was involved in philanthropy. Waldemar Haffkine had no family. So he left all his fortune (500,000 francs) to the Young Scientists Fund.

Władysław Turczynowicz-Wyżnikiewicz and his plague vaccine in Central Asia

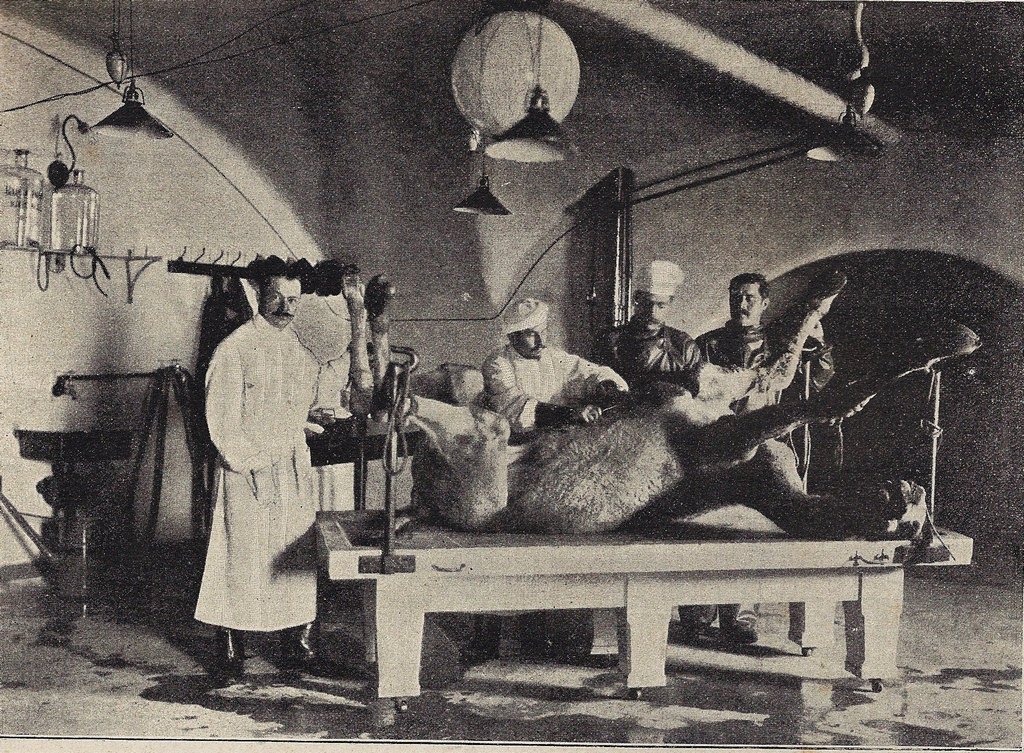

Władysław Turczynowicz-Wyżnikiewicz, a veterinarian doctor, died one year before his fortieth birthday. The bubonic plague killed him in three days in his laboratory at Fort Alexander I in Kronstadt. It happened during Christmastime of 1904. He died of the pneumonic plague, the most virulent form of the disease. It is so deadly that 50% of people infected during its epidemic in Madagascar in 2013 died despite all the advanced methods of control.

The scientist was the head of the laboratory at the Imperial Institute of Experimental Medicine. It was the place where plague vaccines were developed. It was long before his death and at almost the same time with Haffkine that he managed to create an experimental vaccine against the plague that was used during the epidemic in Turkestan in 1898.

Władysław Turczynowicz-Wyżnikiewicz at the autopsy of a plague-infected camel. Photo credit: pastvu.com

The epidemic broke out in the kishlak of Anzob in the mountains of the Gissar Range that run between Turkestan and Southern Bukhara. It was caused by severe unsanitary conditions and the prejudices of the local inhabitants, mullahs, and rulers, which hindered the Russian authorities from taking measures to prevent or contain the epidemics. Shortly before that, during the cholera epidemic in Tashkent in May and June 1892, enraged fanatics attacked the military commandant Stepan Putintsev in an attempt to resist the sanitary requirements for burying the remains of the deceased. As a result, the authorities had to use force.

The plague vaccination campaign curbed the epidemic in the region. Nevertheless, it was up to the 1930s that local religious fanatics often called (and sometimes these calls were brought to action) to kill Russian doctors when they came to the kishlaks to vaccinate people against plague, cholera, and other highly infectious diseases.

Childhood diseases in Russia

Diphtheria

In contrast to smallpox, cholera, and rabies, there were no vaccines against so-called childhood diseases, such as pertussis, diphtheria, measles, and others, at the end of the 19th century. One of the diphtheria epidemics that broke out in the area of the Don in 1869 killed almost the entire junior generation in many of the farmsteads of the Don Cossack Host. Come to think of it, the diphtheria epidemics broke out in the Empire almost every four years.

In 1891, medical doctor Emil von Behring saved a child's life by administering the world's first vaccine against diphtheria. By 1895, antidiphthetheric serum was widely used in Russia despite its serious side effects, such as high fever and occasional seizures. However, those side effects did not scare the parents who had been losing their children to these horrible diseases for generations. According to one of the reports of the Chief Medical Officer at the beginning of the 20th century, the population had a high level of confidence in serum injections and brought their children for vaccinations voluntarily.

Polio control

In the middle of the 20th century, the world had another epidemic to face. That time it was poliomyelitis. In the Soviet Union, the first epidemic broke out in the Baltics, Kazakhstan, and Siberia in 1949. The disease killed 10 percent of the affected people, leaving another 40% disabled.

Jonas Salk, a U.S. scientist, invented the first polio vaccine. Later on, a cheaper and more efficient vaccine was developed by Albert Sabin in the United States, Mikhail Chumakov, and Anatoli Smorodintsev in Russia. They tested it on their children and grandchildren being confident that no side effects could result and that human lives would be saved.

Children affected by polio. Photo credit: ivkult.ru

Mass vaccination campaign followed successful tests. The Soviet Union managed to eradicate poliomyelitis within eighteen months. 77.5 million children were vaccinated by 1960. In later years, Chumakov came up with the idea of vaccination without the needle. He added the medication to special candy dots, thus significantly facilitating the vaccination process.

Back then, the world also did not believe that the vaccination campaign had been so effective. During our delegation's presentation at an international conference in Washington, one of the participants shouted out that the West did not believe the information received from Russia. The reply was, "We love our children no less than you love yours." And the audience broke out into applause.

In 1963, Mikhail Chumakov and Anatoli Smorodintsev were awarded the Lenin Prize. The annual symposium at the Institute of Poliomyelitis and Viral Encephalitis of the USSR Academy of Medical Sciences was attended by leading scientists from the USA, Japan, Europe, and China. More than 60 countries imported vaccines produced by the Institute.

Influenza

Influenza vaccination was introduced in Russia back in the 1970s. However, it was not of a large scale at that time. Mass vaccination campaign against influenza was initiated in Russia due to the pandemic threat in 2009-2010. Now the vaccination is included in the National Immunization Schedule and is provided free of charge. According to Rospotrebnadzor data, 49% of the country's population, that is 70.8 million people, were vaccinated last year. Doctors reported that these measures had reduced the incidence of flu from 5173.8 cases per 100,000 people to 26.5 cases since 1997, which means a nearly 200-fold decrease.

Epidemiology is a matter of state

Renowned French scientist Louis Pasteur is the founding father of immunology and systemic vaccination. Back in 1881, he discovered a vaccine against anthrax. His discovery was a real salvation for all those bitten by rabietic animals in 1885. For example, 44 infected peasants from Tver, Kostroma, Vladimir, Smolensk, and other Governorates went to Paris from Russia. Most of them were bitten by rabietic wolves. Alexander III ordered to give the peasants infected with rabies the funds for a trip to Paris where they were cured by Pasteur. He was requested to do so by the chief procurator of the Holy Synod Konstantin Pobedonostsev. Later on, the Russian emperor donated more than 100,000 francs to establish the Pasteur Institute (the world's first institute of immunology) in Paris.

The first rabies vaccination station in the Russian Empire was opened in Odessa on June 11, 1886. It was arranged by Ilya Mechnikov (also written as Élie Metchnikoff) who was teaching at the Novorossiysk University back then. He worked together with such prominent Russian scientists as the physiologist Sechenov, the zoologist and embryologist Kovalevsky, and the physicist Umov. A month later a similar medical station was established in Moscow. One of the people behind its opening was Nikolay Sklifosovsky, the future founder of Russian military field surgery. That station became the basis for the world-renowned Moscow Research Institute of Vaccines and Sera named after I. I. Mechnikov to be founded on.

Ilya Mechnikov was the first scientist in the world who summarized data on the course and effects of vaccination into a unified scientific immunity theory. He also studied the causes of individual insusceptibility to infectious diseases. Authors of the theory of immunity, namely Ilya Mechnikov, a Russian scientist, Paul Ehrlich, German immunologist and the founding father of chemotherapy, were awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1908.

Epidemiology in Russia has been a matter of state since the reign of Catherine the Great. Russian science gradually established itself as a leader in the field of infectious disease epidemiology, and it retains this position to this day. In this context, it is quite emblematic that the world's first educational department of epidemiology was opened at Novorossiysk University in Odessa. Its founder Danylo Zabolotny (who used to work with Waldemar Haffkine in India and with Władysław Turczynowicz-Wyżnikiewicz in Fort Alexander I) wrote the first textbook on epidemiology.

Russian scientists were the inventors of the first vaccine against the dreadful Ebola fever. The first vaccine was invented at the Gamaleya Center in 2016. The second one was developed at the Vector Center, Novosibirsk. The U.S. analogs were introduced by Merck & Co. (MSD) and Johnson & Johnson only in 2019.

Photo credit: E. Samarin / mos.ru (CC BY 4.0)

As of today, 4 vaccines against COVID-19 have been released in Russia.

-

The first vaccine in Russia and in the world was the Gam-COVID-Vac combined vector vaccine (trademark: Sputnik V) by the Gamaleya Research Institute of Epidemiology and Microbiology of the Ministry of Health of Russia. It was registered on August 11, 2020;

-

The second Russian development is the EpiVacCorona peptide-based vaccine by the State Research Center of Virology and Biotechnology VECTOR of Rospotrebnadzor;

-

The third one is the CoviVac inactivated whole-virion vaccine by the Chumakov Federal Scientific Center for Research and Development of Immune-and-Biological Products of the Russian Academy of Sciences. All of the above items have been released.

-

Furthermore, Sputnik Light, a stand-alone one-shot vaccine against COVID-19 by The Gamaleya Center, was registered on May 18.

* It originates from the Russian word “ryaboy” meaning pocky

**The surname’s origin is the Russian word “shchedra” meaning pockmarked

New publications

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.  Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.

Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.  When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.  Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."

Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."  "Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...

"Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...