Editor’s office of the Russkiy Mir Foundation internet portal

The press-center of the Rossiya Segodnya News Agency presents Poland’s Struggle for Eastern Europe in 1920–2020. The book’s authors believe that the current eastern policy of Poland is a complex blend of old geopolitical concepts and undying national fixations.

Renaissance of old ideas

Veronika Krasheninnikova, Director General of Institute for Foreign Policy Research and Initiatives and the book’s publisher, emphasized that the authoring team had aimed to case study Poland’s eastern policy over the past 100 years, that is, following its independence after the First World War and until today.

According to Russian experts, including well-known experts in Poland studies, historians and political scientists, the Intermarium concept lies at the core of Polish policy autonomy towards its eastern neighbors. This is a geostrategic project to unite the states of Eastern Europe under the Polish leadership. It was proposed by the Polish dictator Marshal Józef Piłsudski a hundred years ago.

Marshal Józef Piłsudski. Photo: ru.wikipedia.org

The above mentioned concept had serious consequences. Poland’s intransigent attitude towards the Soviet Union dissuaded it from the dialogue on joint counteraction to Nazi Germany; instead, in the 1930s Warsaw even hatched schemes for unification with Germany against the USSR.

The possibility of such an alliance was understood - and feared in the Soviet Union. According to Dmitry Surzhik, one of the authors of the book and a department member of the Center for History of Wars and Geopolitics of the Institute of World History of the Russian Academy of Sciences, back in 1938 Boris Shaposhnikov, Chief of the Staff of the Red Army, presented a memorandum report with a scenario for the strategic deployment of the armed forces. The scenario provided for possibility of a war between the USSR and the German-Polish alliance.

As we know, back then Poland’s plans collapsed, the country fell victim to Hitler’s aggression, and then for many decades it was in the orbit of a new superpower - the Soviet Union. However, the project soon reemerged - first in the minds of Polish emigrants in Europe and America, and since the 1990s, this concept has found new life with the support of the US.

The book aims to discuss the set of issues related to this policy of Poland.

Dmitry Bunevich, the publication editor and director of the Institute of Russian-Polish Cooperation, emphasized that the authors had done their best to keep discussion on relations between Russia and Poland at a high academic level. The readers will have a fairly broad overview of Poland’s struggle for dominance in Eastern Europe starting from the Soviet-Polish war of 1919-1921. Moreover, that overview is free from journalistic biased approach. At the same time, the book pays a lot of attention to post-Soviet political relations in the region.

Dmitry Bunevich gives the following assessment to the current policy of the Polish leadership:

– We observe a renaissance of old ideas; and Piłsudskians come up again and try to reanimate the failed Intermarium project. Poland is a country that pursues its own foreign policy line, and such agenda raises concerns.

The reanimated Intermarium Concept had its forerunner.

“For our freedom and yours”

Historian Tatiana Simonova wrote an article about Polish Prometheism for the collection. This concept dates back to the time of Piłsudski and states that the Polish people, just like Prometheus who brought fire to men, bring freedom to the enslaved peoples of the Soviet Union.

The historian sees origin of Polish Prometheism in famous words associated with the times of the November Uprising in 1830: “In the name of God, for our freedom and yours.” They were most probably authored by Joachim Lelewel and became a slogan of Polish patriots.

Banner of Polish rebels 1831. Photo credit: ru.wikipedia.org

The concept saw the major development in the interwar period under Józef Piłsudski. Vladimir Vanchkovsky, the Prometheism ideologist in those years, wrote: "It is better to be an organizer of the war initiated by us than to be a German outpost or a Soviet staging ground and buffer." It is a quote from his 1938 work; just a year later Poland was crushed by the very war that he had prophesied.

Back then Prometheism was suggested as a state policy. State structures, such as Ministry of Internal Affairs, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and the War Office, were involved in its development. It was a secret, underground policy.

The objective of the Prometheism policy was ethnic cleavage of Russia. Later on the idea was taken by American policymakers, but they drew upon Polish theoretical developments.

– They mainly worked with emigrants, primarily Ukrainian émigré community, because Ukraine is the pole star of Prometheism, it is the foundation, the staging ground, - said Tatyana Simonova. They also worked with emigrants from the North Caucasus and Central Asia, but to a lesser extent.

The Poles also had projects related to the Cossacks - it was assumed that after the cleavage, the Cossacks would also have their own state formations.

In the post-war period, the Prometheism ideologists continued their work in London. However, a new stage of plan implementation commenced only in the 1980s. It marked the so-called period of Neoprometeism.

Prometheus Brings Fire to Mankind by Heinrich Füger, 1817

– Unfortunately, Prometheism is an integral part of Polish national identity and it will be constantly restored to life. It is also an integral part of Polish intellectual life, - Tatiana Simonova summarized the talk.

Gennady Matveev, professor of History Department of Lomonosov Moscow State University and renowned expert in Poland’s interwar history, contributed the book with an essay on characteristic and institutional features of Polish foreign policy. “It was interesting for me why a country that had been absent on the political map of Europe for 123 years, a country that revived with support from the West, the Entente back then, set a course for becoming a great power right from the start,” he shared.

While analyzing various explanations of this phenomenon, primarily on the basis of Polish reports, Professor Matveev concluded that the reasons should be sought in the state security issues recognized by the Polish leadership.

The Russian historian believes that Polish ruling elite was keenly aware of the curse of Poland - that it was caught in a vice – between Russia and Germany.

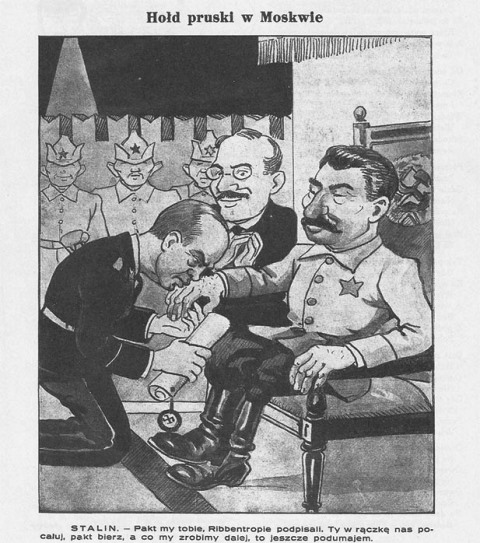

Polish caricature of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact "Prussian oath in Moscow."

Caption: “STALIN - We have signed your pact, Ribbentrop. You’ll kiss our hand, take the pact, and we will see what to do later... ”

– This is the fear that lives very deep within them, – the Russian historian believes.

However, they did not look for a way out of this difficult situation through cooperation or reconciliation. The bid was placed on regional hegemony: Poland was to gain the position of a large and strong state in Eastern Europe, to be a center point for other smaller states to stand behind.

And since the very beginning, the main task was to cleave the Russian Empire, and then the Soviet Union.

Anyway, history is history, but what view on eastern policy does the contemporary Poland have?

Polish narratives

Alexander Nosovich, director of the Baltic Research Media Center (Kaliningrad), is sure that the narrative changed in both the domestic and foreign policies of the Rzeczpospolita in 2015, after Law and Justice, a conservative political party, had come to power.

Previously the main items on the agenda were democratization, establishment of market economy, and westernisation of social and cultural life, but after 2015 Poland has started positioning itself not just as an integral part of the Western world, but as its “proper” part, which should serve as a role model for both East and West. “Such narrative has been the basis for the entire domestic and foreign policy of this state since 2015,” the Kaliningrad political scientist believes.

Alexander Nosovich explains:

– It is implied that Poland should be a role model for both the United States and Western Europe to prevent them from falling into the socialist system that the Poles managed to get out of.

The West, which is actively drifting to the left wing, has lost its true values, but Poland, with the immunity to socialism acquired in the Soviet years, managed to preserve the true values and it should transmit them to the world. This also applies to refugee policy, preservation of traditional Christian values in society, etc. Such is the ideology of the current Polish leadership.

Speech by Jarosław Kaczyński, the head of Law and Justice, under the slogan “Poland is the heart of Europe”. Photo credit: Lukasz G¹gulski / Source: PAP

– Elements of messiahship aimed also to the West are traditional for Poland. Too see that, it is sufficient to read books by Sienkiewicz,” - asserts the political scientist.

The current eastern policy of Poland is fed from the same source: official Warsaw believes that the West is not strong and consistent enough when it deals with anything related to the post-Soviet space. And the first instance is the Ukrainian issue.

It is no coincidence that having returned to power in 2015, Law and Justice criticized the Eastern Partnership program, which Poland and Sweden lobbied for in the European Union. They are not happy that this program does not intend to separate the former Soviet republics from Russia. Poland’s position is straightforward: Ukraine should be accepted into the EU and NATO; political elite in Belarus should be replaced and respective transition shall commence. And Poland should act as the supervisor and mentor for both countries.

Moreover, the current leadership of Poland prefers to demonize Russia.

As a representative of Kaliningrad Region, Alexander Nosovich brought to notice the well-known Polish doctrine of Gedroits and Meroshevsky, according to which it is advisable for Poland to avoid having common borders with Russia and to fence itself off by buffer states. However, such border exists - it is located in Kaliningrad Region. According to the expert, over the decades of its existence, Kaliningrad has not posed any threats to Poland, which disproves the abovementioned doctrine. On the other hand, good practices of cross-border cooperation have been developed. The most successful one of them was a visa-free border regime, which significantly improved economy of near-border Polish provinces.

Alexander Nosovich believes:

– The fact that today the Polish leadership resumes demonization of Kaliningrad Region as a Russian outpost to conquer Europe proves that the Polish elites do not want to abandon illusions that dominate their minds and shape Polish policy.

Neo-Atlantic future of Poland

The world has been rapidly changing. It is prevailed by uncertainty. What shall we expect from Poland within the framework of European security that is undergoing a significant transformation?

Gennady Matveev stated, and some panelists agreed with him, that Poland’s policy was now predictable. The upcoming parliamentary elections will again provide Law and Justice with predominance, so any serious changes in Polish politics are very much unlikely in the near future. Poland will continue attempts to implement its policy in the East. However, as the Russian expert noted, Poland’s major neighbors, i.e. the European Union and Russia, do not share those plans of Poland, and Ukraine actually does not need Polish supervision since it has mentors of much higher profile.

Donald Trump and Andrzej Duda, President of Poland. Photo credit: politobzor.net

Nevertheless, another part of the experts believes that Poland deserves to be taken seriously. “Unfortunately, it is impossible to remove the “Russian complex” from Polish psychology,” Tatiana Simonova said. The historian was supported by Aleksander Nosovich, a political scientist. According to him, Poland should not be taken light-mindedly, or it could become a huge problem in the future. This is a large and growing European country with great ambitions, and it must be closely monitored.

The expert insists that Poland’s activity largely depends on events overseas. As Veronika Krasheninnikova noted, Poland and the United States have seriously strengthened their relations under Trump. According to Dmitry Surzhik, there is a big chance that power shift in the White House will intensify conflicts in gray areas of the former Soviet territory, and in those conflicts "the Polish elites will see themselves as an important driving belt."

Dmitry Bunevich claims that traditional Atlanticism, which implied a close alliance of Europe and the United States, is being replaced by neo-Atlanticism. Neo-Atlantists do not count on core Europe anymore, since it shows increasing disappointment in both the US hegemony and NATO. They place stakes on a group of new Eastern European states (Poland, Romania, the Baltic countries, and, again, Ukraine) that line up behind the United States. These countries of new Europe will be a tool of pressure on Brussels, where they torpedo all initiatives aimed to strengthen independence of the European Union, and on Russia. “Poland will become a key player in this neo-Atlantic strategy in Eurasia for quite some time,” the political scientist insists.