A Russian New Year

/ Главная / Russkiy Mir Foundation / Publications / A Russian New YearA Russian New Year

Polina Skolkova

Until the end of the 15th century, the new year began on 1 March in Old Rus (as in Ancient Rome), and then until the end of the 17th century it began on 1 September (as in Byzantium). With his decree “On Celebrating the New Year” at the end of 1699, Peter the Great replaced the practice of counting years “from the creation of the world” to “from the birth of Christ.” Since then, Russia has celebrated the New Year in European fashion.

With one flourish of the pen, Peter the Great transferred Rus from the year 7208 to 1700. Then, the tsar cited the tradition of “European Christian countries,” including the Slavs and Orthodox Serbs, Moldavians, Bulgarians, and Greeks. “And now the year 1699 since the birth of Christ is arrived, and from the first day of the coming January the new year, 1700, and a new century will begin; and for this good an useful cause I have ordered hence for the year to be counted in all orders, and all business and garrisons, from the first of this January as the year 1700 since the birth of Christ,” said the tsar’s decree.

The tsar also ordered the coming of the new year and new century to be celebrated as in Europe: “after due thanks has been rendered to God and the prayers have been sung in church, whosoever is concerned shall in their homes, along the major streets and eminent throughways, among distinguished individuals, and in the homes of important persons of spiritual and lay ranks, shall establish certain decorations from trees and boughs of pine, fir, and juniper.”

People had a simple outlook. The tsar was father and lord to all of his subjects, and therefore there’s nothing surprising about the fact that the decree also regulated how to celebrate the first day of the new year in some detail: what to shoot on the occasion of the holiday (analogous to a celebratory salvo), how many times to fire it, and how and when to light the celebratory bonfires.

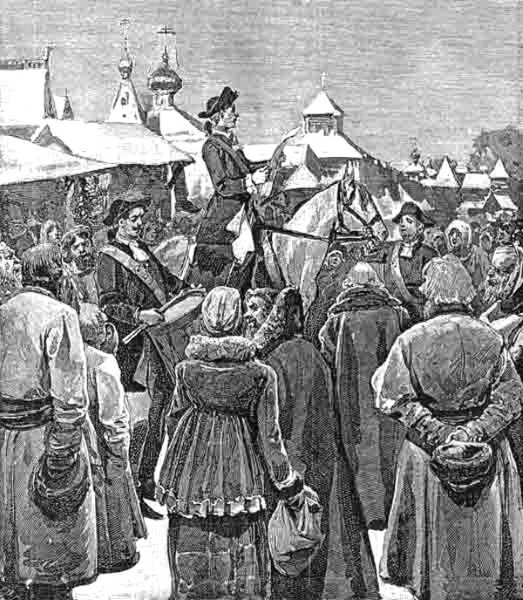

[Unknown artist, “Announcement of Peter the Great’s Order to Count the New Year Starting on 1 January”]

“Such ringing had not been heard in Moscow for a long time. They said: Patriarch Adrian, not daring to contradict the tsar in any way, gave the bell-ringers a thousand rubles and fifty barrels of the patriarch’s strong beer. Squatting, they rang the bells in the steeples and bell towers. Moscow was wrapped in smoke and fumes from the horses and people…

Through the ringing of the bells all across Moscow, shots crackled and cannons bellowed in a bass. Dozens of sledges rushed along at a gallop, full of drunkards and mummer smeared with soot and wearing their fur coats inside out. The riders stretched their legs, waved around bottles, raised a ruckus, and on the slopes they would roll out in heaps at the feet of the simple people, who had grown woozy from the ringing and smoke…” (A. Tolstoi, Peter I)

The custom of decorating houses with coniferous branches and trees was forgotten after Peter the Great’s death, and it was renewed only toward the end of the 18th century. One way or another, the tradition of widely celebrating Christmas and the New Year in Russia has been around now for more than three hundred years, and that’s no joke. In this time, masquerades, all kinds of merriments, festival firs, and the other attributes of the winter holiday have made a lasting contribution to Russian life, and to Russian art as well.

[Vasily Surikov, “Great Masquerade of 1722 on the streets of Moscow Involving Peter 1 and Lord Prince I. F. Romodanovsky,” 1900]

[Boris Kustodiev, “Fir Tree Sale,” 1918]

[Sergei Dosekin, “Getting Ready for Christmas,” 1896]

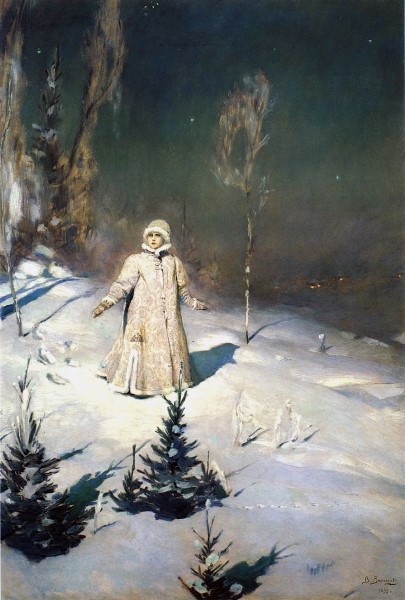

[Viktor Vasnetsov, “Snegurochka,” 1899]

[Konstyantyn Trutovsky, “Carols in Little Russia,” 1864]

[Nikolai Feshin, “Christmas celebration,” 1917]

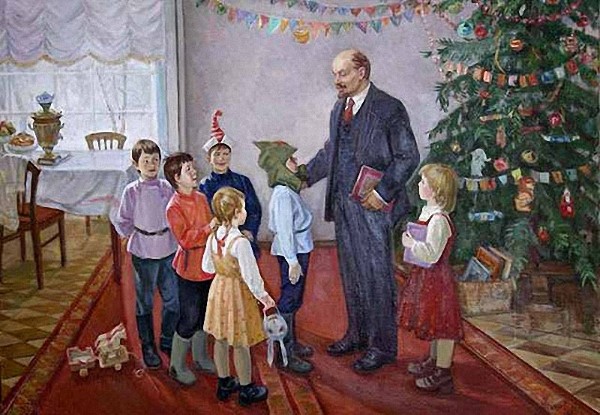

Up until the early 20th century, the fir tree and accompanying celebration were considered a Christmas tradition. When they came to power, the Bolsheviks adopted the tactics of Christianity in its fight against paganism: they maintained the holiday, but in a severely reduced form. Every association with Christ’s birth was driven away.

Despite the popularity of the subject “Lenin at a holiday party” in Soviet painting, in reality the fir tree and Old Man Frost were abolished in Soviet Russia in the early 1920s. In 1929, the Christmas holiday was officially abolished as well. After a little “rebranding,” it returned as the New Year’s holiday in 1935, on the recommendation of Alexander Poskrebyshev, Head of the Special Section of the Central Committee.

[Unknown Artist, “V.I. Lenin at a celebration in Sokolniki”]

“Vladimir Dmitrievich, would you like to take part in a children’s holiday?” Vladimir Ilich [Lenin] asked me.

“I would,” I said.

“Well then, go somewhere to get gingerbread cookies, candies, bread, noise makers, and toys, and we’ll go tomorrow to drop in on Nadya at the school. We’ll have a celebration for the children, and here’s some money for the expenses.” (Vladimir Bonch-Bruevich, “At a School Holiday Party”).

In 1935, the fir tree, Old Man Frost, and gifts under the tree appeared once again. But the attributes of the old Christmas celebration now passed on to New Year’s. Two years later, Father Frost took on a constant companion at holiday celebrations—Snegurochka. It was at this time that the holiday acquired its canonic look, which is how we all know it.

[Tamara Zebrova, “Children’s Holiday,” 1941]

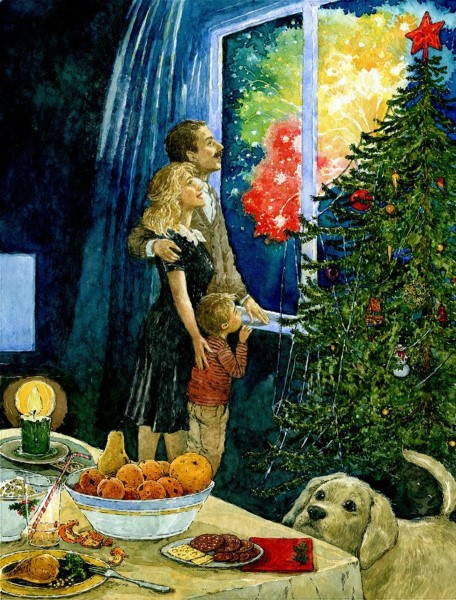

[Aleksandr Guliaev, “New Year,” 1967]

In 1954, the most important fir tree in the country was lit for the first time—the one at the Kremlin.

[Ivan Tikhii, “For you and your friends, the fir tree at the Kremlin shines brightly every year.”

Illustration in Barvinok magazine, 1956]

Over time, new details emerged: the mandatory mandarins, champagne, and Olivier salad on the table; the playing of chimes, at which time one must make a wish; a ceremonial address from the head of state. New Year’s sparklers and table spreads came into fashion.

[Olga Vorob’eva, “Happy New Year!” 2009]

[Andrei Andrianov, “Mayonnaise Salad,” 2012]

[Liudmila Pipchenko, Illustration to E. Rakitina’s The Adventures of New Year’s Toys]

New publications

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.  Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.

Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.  When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.  Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."

Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."  "Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...

"Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...