Rejecting the Russian Language is a Blow to UkraineРђЎs Future

/ лЊл╗л░л▓лйл░ЛЈ / Russkiy Mir Foundation / Publications / Rejecting the Russian Language is a Blow to UkraineРђЎs FutureRejecting the Russian Language is a Blow to UkraineРђЎs Future

Denis Tatarchenko

svpress.ru

Petro Poroshenko signed the law “On Education,” which was ratified by the Ukrainian parliament on 5 September. This reform—which cut back the hours for studying the natural sciences, introduced a 12-year course of study, and reduced the quantity of budgeted positions in institutions of higher educationРђћprovoked a response for another reason: its linguistic impact.

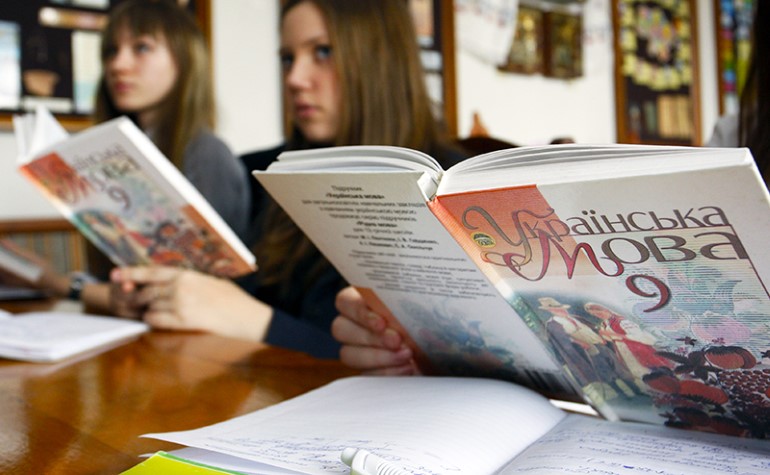

This document, which has become an object of international scandal, provides for the total Ukrainization of the teaching process in state institutions of education. According to the ratified law, starting in 2018 children will be able to study academic subjects in their native language only at the beginning stageРђћup until the fifth grade. Then, for grades five through nine, all schools will gradually introduce subjects in Ukrainian. In the upper classes, absolutely all subjects will be taught in Ukrainian. Beginning in 2020, the entire educational sequence, beginning in kindergarten and ending at university, should fully transition to using Ukrainian.

The earlier law РђюOn EducationРђЮ indicated that questions about the language of instruction in schools would be regulated by the law РђюOn the Foundations of State Language Policy,РђЮ which is still in effect to this day and guaranties minorities the right to receive an education in their native language. No one is upset that this new law enters into contradiction with those already in effectРђћthere are already so many such legal collisions in Ukrainian legislation that the government leadership has stopped paying attention to them.

Unhappy Neighbors

The document provoked a serious scandal at an international level, one that happens to involve countries thought to be allies of Ukraine.The Hungarians were the first to react. The very next day after ratifying the document, on 6 September, the Hungarian Secretary of State for National Policy, Árpád Janos Potápi announced that the new law impinges on the rights of the 150,000 members of the Hungarian diaspora who are primarily concentrated in Zakarpattia, runs counter to the Ukrainian Constitution, and contradicts prior agreements between the two countries. Potápi expressed his hope that this law will nonetheless not be enacted in Ukraine in its current form. After some time, the Hungarian Minister of Foreign Affairs Péter Sijjártó was even more categorical: he called the ratified law a Рђюknife in the backРђЮ and ordered Hungarian diplomats not to support Ukraine’s initiatives in any international forum. Next came complaints against Ukraine to the General Secretary of the OSCE, the High Commissioner of the UN for Human Rights, and the Special Commission of the EU.

The Hungarian parliament also unanimously condemned the new Ukrainian law. And after the Ukrainian President signed it, the Hungarian Ministry of Foreign Affairs told Kiev directly that they could forget their plans to become a member of the EU. Experts have started talking about how Hungary could achieve a suspension of the Ukraine-EU Association Agreement whenever they wished. And this is much more substantial than any threat of blocking a mythical Ukrainian membership in the European Union.

┬аItРђЎs wholly possible that Romania will also join in taking revenge on Kiev. Following the lead of its northwestern neighbor, Bucharest took a deep concern in the status of national minorities in Ukraine. On 7 September, the Romanian Ministry of Foreign affairs disseminated a statement accusing Kiev of impinging on the Romanian minority. Then, in the course of a conversation with the Ukrainian ambassador, the Minister for Romanians Abroad Andreea Păstîrnac emphatically recommended that Kiev not deprive the Romanian community of the opportunity to teach their children in their native language.

Romanian President Klaus Iohannis had made a quite forceful gesture addressed to Kiev: he has completely canceled his planned visit to Ukraine this October. The Romanian president didnРђЎt make any grand declarations, though he discussed the issue of the Romanian minority in detail with Poroshenko at the General Assembly of the UN in New York. The countryРђЎs parliament passed a law condemning the resolution. The total population of ethnic Romanians in Ukraine is around 150,000 people, same as the number of Hungarians.

Moldovan President Igor Dodon did not support the new law. He observed that these changes directly affect the Romanian and Moldovan communities in Ukraine and drive them to de-nationalization. The number of ethnic Moldovans in Ukraine is around 260,000, and their close-knit communities are primarily concentrated in the Odessa oblast.

Greece and Bulgaria also condemned the law, even though there are no schools in Ukraine where Greek or Bulgarian is the language of instruction. WhatРђЎs more, since 2014 the Greek and Bulgarian communities in Ukraine have shrunk significantly. The Greeks, who live predominantly in the Pryazovia part of the Donetsk oblast, started to leave en masse for their historical homeland after the conflict in Donbass began. The Bulgarians too, many of whom lived in the Odessa oblast, have also started leaving Ukraine, though not as actively.

Strangely enough, the most restrained reaction came from the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs. This office for foreign policy promised to Рђюfollow intentlyРђЮ how the new law is enacted. In their statement, Polish diplomats also let slip a strange phrase: supposedly, Warsaw was convinced that Ukraine would undertake all necessary measures to assure Polish children could study in Polish.

In its statement, the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs proclaimed that the Ukrainian law РђюOn EducationРђЮ violated the nationРђЎs Constitution and its international obligations in the humanitarian sphere. The Press Secretary for the Russian President, Dmitry Peskov, expressed concern and declared that the Kremlin didnРђЎt find the ratified law Рђюcontemporary or successful.РђЮ Deputies from the State Duma and Federation Council also came forth with statements condemning the new Ukrainian law. In their statement, the deputies of the State Duma called this law an Рђюact of ethnocide against the Russian people in Ukraine.РђЮ The deputies emphasized that the norms of this law trample on the main standards of the UN and the European Council regarding the defense of the linguistic distinctness of indigenous populations and national minorities, enshrined in international treaties ratified by Ukraine.

РђюThis is a serious blow to Ukrainian identity,РђЮ says the Chairman of the State Duma Committee on Education and Science, Vyacheslav Nikonov. РђюBecause bilingualism has always been a defining characteristic of the Ukrainian nation. After all, itРђЎs no accident that such a major symbol of Ukraine as Taras Shevchenko wrote poems in Ukrainian and his diaries and prose in Russian. Ukrainian heritage consists precisely in this. To deprive Ukrainian citizens of the Russian language is to reject the competitive edge to be gained from knowing a language of global import.РђЮ The lawmaker believes that the new law РђюOn EducationРђЮ is politically dangerous for the Ukrainian leadership, insofar as it strikes the blow to the countryРђЎs cohesiveness. РђюItРђЎs obvious that the Russian-speaking citizens of Ukraine will defend their right to speak in their native language one way or another,РђЮ the politician suggests.

Only the US embassy in Ukraine tweeted congratulations to Kiev on the passage of the educational reform. By the way, this is not surprisingРђћafter all, this legislative proposal would scarcely have become law if Washington were against it.

Not Against Hungarians and Romanians

It would be naïve to think that the law signed by Poroshenko was targeted at Polish, Hungarian, Romanian, or Moldovan communities. The overall number of schools conducting classes in the languages of these minorities comprises 1% of the total number of schools, and their members make up an even lower percentage of the Ukrainian population. Their languages are hostages in another, more important battle that has been waged by the Ukrainian government since it acquired independenceРђћthe battle against the Russian language.

РђюSuch a law is only one link in a long-standing trend in Ukrainian internal politics that has developed by degrees since the presidency of Kuchma,РђЮ comments Sergei Provatorov, a member of the Global Coordinating Council of Russian Compatriots from Ukraine. РђюAnd thereРђЎs no doubt that this wonРђЎt be the last normative act aimed at repressing the Russian language and manifestations of Russian culture from all spheres of social and governmental functioning. Along with the prohibition on using the Russian language in record keeping and the introduction of quotas for language use on television and radio, the prohibition of Russian-language teaching is a predictable and РђюlogicalРђЮ step by the Ukrainian political leadership who had already determined just this course long before taking control of state institutions. And the fact that this new version of the law on education has liquidated the right to an education in oneРђЎs native language for children of all national minorities is to a significant degree a casualty of the decisions made against the Russian language. This language is the main point of concentration and transmitter for the entire Russian cultural heritage. Political Ukrainianism is waging its primary battle against this target.РђЮ

Beginning in 1991, the number of schools in Ukraine with Russian as the language of instruction has been dropping consistently. In the 2016-2017 school year, the proportion of all schools (private and public) with lessons in Russian was 9.4%, while the Russian and Ukrainian languages maintained parity at the moment when Ukraine acquired independence in 1991: 49.3% of schools used only the Ukrainian language and almost the same number of educational institutions conducted classes in Russian. According to the information of the Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine, during the 2016-2017 school year 581 schools and 364 kindergartens still used only the Russian language. More than 355,000 children study at schools where classes are conducted entirely in Russian. Around 920,000 schoolchildren study the Russian language as an individual subject, 65,000 people attend elective courses and practice circles, around 3,000 study Russian at colleges, and almost 27,000 study at other institutions of higher education.

Even during the Yanukovich presidency, when Dmytro Tabachnik was criticized by the Ukrainian Minister of Education for Рђюfavoring Russianness,РђЮ the percentage of Russian-language schools kept dropping. Of course, this didnРђЎt happen for the sake of ideology but under the vaunted banner of РђюoptimizationРђЮРђћthese institutions simply closed, and the children were transferred to Ukrainian-speaking schools.

РђюMy neighbor comes from Ryazan,РђЮ a Russian instructor in a central Ukrainian town tells Russkiy Mir, asking to remain anonymous. РђюLast year they dropped the class taught in Russian at his granddaughterРђЎs school. All 28 children transferred into a class taught in Ukrainian, despite their parentsРђЎ indignation. No oneРђЎs listening to anyoneРђћthey just present them with the fact that there arenРђЎt any other schools.РђЮ

Meanwhile, the demand for Russian-language education greatly exceeds the offerings. According to the 2001 census, 17.2% of the Ukrainian population identified themselves as ethnic RussiansРђћthatРђЎs more than 8 million people. Now, that number is lower. (After all, a large portion of the Russian residents in these statistics lived in the Crimea.) However, Russian-language schools arenРђЎt needed only for those Ukrainian citizens who identify as Russian. Now, according to various statistics, Russian remains the native language for 30-40% of the countryРђЎs population, which is around 15 million people. Even before this new law, many parents were forced to send their children to private schools due to the lack of Russian-language public schools. Beginning in 2018, these schools will also be Ukrainized.

РђюItРђЎs clear that Russian always represented for Ukraine the language of culture, the language of industry, and the language of the urban intelligentsia. Of course, teaching students in a non-native language reduces their ability to master the material. This is an axiom. That is, all of this is a blow to the countryРђЎs intellectual potential,РђЮ says Vyacheslav Nikonov.

And whoРђЎs stopping you? Minorities Will Study Your Native Language

In response to criticism of the new law, which, incidentally, Poroshenko signed without waiting for the results of legal experts in the European council, the head of the government assured that РђюUkraine had demonstrated and will continue to demonstrate an attitude toward the rights of national minorities that corresponds to our international obligations, harmonizes with European standards, and is an example for neighboring countries.РђЮ What does this statement mean?

Most likely, the languages of these national minorities will remain in place as subjects in certain schools, where parents will choose them as an additional foreign language. In accordance with the new law, English will become the primary and required foreign language in schools. And the Russian language, which is native to millions of Ukrainian citizens, will occupy a place of honor alongside German, French, Spanish, Italian, and other foreign languages that are important, but not required.

New publications

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.  Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.

Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.  When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.  Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."

Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."  "Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...

"Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...