Revelations in Soviet President’s Personal Files

/ Главная / Russkiy Mir Foundation / Publications / Revelations in Soviet President’s Personal FilesRevelations in Soviet President’s Personal Files

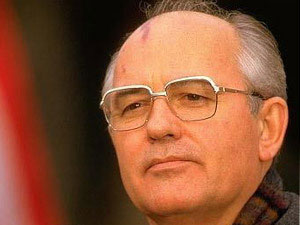

The German weekly Der Spiegel is publishing materials concerning Mikhail Gorbachev. The documents presented by the publication were copied from the personal archives of the former Soviet president by Russian historian Pavel Stroilov, who presently resides in Moscow. With the help of these materials journalist Christian Neef is attempting to find answers to some long-burning questions: what were Gorbachev’s motives, when did he begin perestroika and why was this experiment a failure? The German journalist also accuses Gorbachev of duplicity and says he was “driven to act by developments in the dying Soviet state and that he often lost track of things in the chaos.”

The official papers from much of Gorbachev’s time in power were preserved. He took them with him when he announced his resignation as the Soviet president at the end of the year, and donated them to the foundation that bears his name. Since then, about 10,000 documents have been in storage at the foundation's headquarters on Leningrad Prospect 39 in Moscow. They include the personal archives of his foreign policy advisers, Vadim Zagladin and Anatoly Chernyaev.

They include the minutes of negotiations with foreign leaders, the handwritten recommendations of advisers to Gorbachev, speaker's notes for telephone conversations and recordings of those conversations, confidential notes by ambassadors and shorthand records of debates in the politburo.

“The papers illustrate the end period of the communist experiment,” Neef writes. None of the issues with which the self-proclaimed reformer of the Soviet Union was confronted in those years has been left out.

There are memorandums in which the Soviet leader is advised on how to end the war in Afghanistan or how to deal with Jews seeking to emigrate, or explaining to him why he should refuse to meet with Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat (“nothing real to be expected from him”) or why he should avoid putting Mathias Rust, a young German aviator who had illegally landed a light aircraft near Red Square, on trial and receive him in the Kremlin instead (“there are questions as to his psychological state”).

There are reports from informers within the East German Communist Party leadership, describing how bad conditions were in East Germany and detailing who could still be depended upon in the East Berlin politburo. And there are equally meticulous reports on what the French magazine Paris Match wrote about Raisa Gorbachova or what the Russian singer Alla Pugacheva told a German magazine about Gorbachev's perestroika policy. The documents also show that even under Gorbachev, the bureaucracy was as inefficient as ever. Gorbachev's aide Anatoly Chernyaev, for example, complains about incompetent leaders in the global communist movement, like French Communist Party leader Georges Marchais (“a dead horse”) and Gus Hall, the chairman of the US Communist Party (“a philistine with plebeian conceits”). “Reading the documents feels like stepping back in time,” the author writes.

Some of the documents from this archive were used in books penned by Gorbachev, “much to the chagrin of the current Kremlin leadership. But many of the papers are still taboo to this day. This is partly because they relate to decisions or people that Gorbachev is still unwilling to talk about. But most of all it is because they do not fit into the image that Gorbachev painted of himself, namely that of a reformer pressing ahead with determination, gradually reshaping his enormous country in accordance with his ideas.”

According to Der Spiegel, the documents “reveal something that Gorbachev prefers to keep quiet: that he was driven to act by developments in the dying Soviet state and that he often lost track of things in the chaos. They also show that he was duplicitous and, contrary to his own statements, sometimes made deals with hardliners in the party and the military. In other words, the Kremlin leader did what many retired statesmen do: He later significantly embellished his image as an honest reformer.”

“The West has praised Gorbachev for not forcefully resisting the demise of the Soviet Union. In reality, it remains unclear to this day whether the Kremlin leader did not in fact sanction military actions against Georgians, Azerbaijanis and Lithuanians, who had rebelled against the central government in Moscow between 1989 and 1991… He also did not call anyone to account later on. Even today, he still says that it was ‘a huge mystery’ as to who gave the orders to use violence in Tbilisi.”

The publication quotes from the protocol of a meeting between Gorbachev and Hans-Jochen Vogel, the then-floor leader of Germany's center-left Social Democratic Party (SPD), on April 11, two days after the bloody suppression of the protests, he sought to justify the hardliners' approach: “You have heard about the events in Georgia. Notorious enemies of the Soviet Union had gathered there. They abused the democratic process, shouted provocative slogans and even called for the deployment of NATO troops to the republic. We had to take a firm approach in dealing with these adventurers and defending perestroika – our revolution.” The Soviet president later had the passage deleted from the published version of the Russian minutes of the conversation with Vogel, the journalist says.

According to the magazine, Gorbachev made the following remark at a politburo meeting on Oct. 4, 1989, when he learned that 3,000 demonstrators had been killed on Tiananmen Square in Beijing: “We must be realists. They have to defend themselves, and so do we. 3,000 people, so what?” Although the minutes of the meeting were later published, this passage was missing.

In January 1991, under pressure from the intelligence service and the military, Gorbachev apparently agreed to what was already a futile venture: sending special Soviet army and state security units to the building housing the state television headquarters in Vilnius, where they stormed the station and killed 14 people. In a telephone conversation with then-US President George Bush two days earlier, Gorbachev had flatly denied that Moscow would intervene in Vilnius. “We will only intervene if there is bloodshed or if there is unrest that not only threatens our constitution, but also human lives.”

A bitterly disappointed Anatoly Chernyaev wrote a letter to Gorbachev following the latter’s speech on the subject before the Supreme Soviet: “Mikhail Sergeyevich! Your speech in the Supreme Soviet (about the events in Vilnius ) signaled the end. It was not an appearance by a great statesman. It was a confused, babbling speech. You are unwilling to say what you really intend to do. And you apparently don't know what the people think about you – outside in the streets, in the shops and in the trolleybuses. All they talk about is ‘Gorbachev and his clique.’ You claimed that you wanted to change the world, and now you are destroying this work with your own hands.”

Former German Chancellor Helmut Kohl figures particularly prominently in the Gorbachev documents. He was greatly indebted to the Russian leader at the time, because Gorbachev had declined not to deploy tanks in East Berlin to stop the collapse of East Germany in the fall of 1989. He also did not stand in the way of reunification the following year. In fact, to the consternation of many comrades in his own ranks, Gorbachev didn't even oppose a reunited Germany joining NATO. But according to the magazine, Gorbachev thought that Kohl was “not the greatest intellectual, but he enjoys a certain amount of popularity in his country, especially among ordinary citizens,” although he was appreciated for his influence in the West. Kohl was able to repay the favor in 1991, which was precisely what Gorbachev expected of him. During this phase, Kohl was, in many respects, Gorbachev's last hope, Der Spiegel writes. “Gorbachev still wanted to be perceived as the leader of a world power, even as he was forced to beg for assistance behind the scenes,” the author notes.

In September 1991, the financial situation in the USSR was so precarious that Gorbachev took then German Foreign Minister Hans-Dietrich Genscher aside while Genscher was visiting Moscow and was forced to abandon any sense of pride and beg for assistance. In a conversation with Horst K

New publications

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.  Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.

Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.  When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.  Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."

Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."  "Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...

"Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...