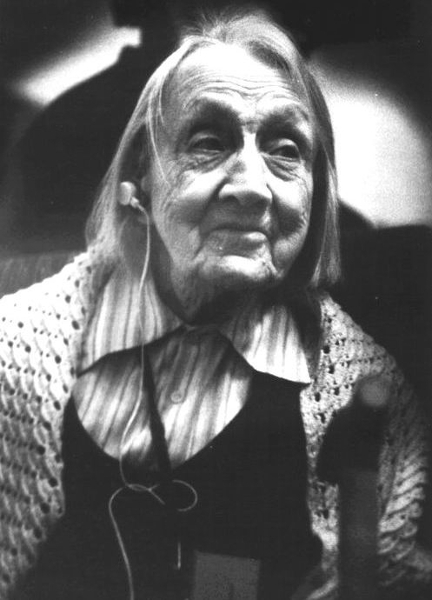

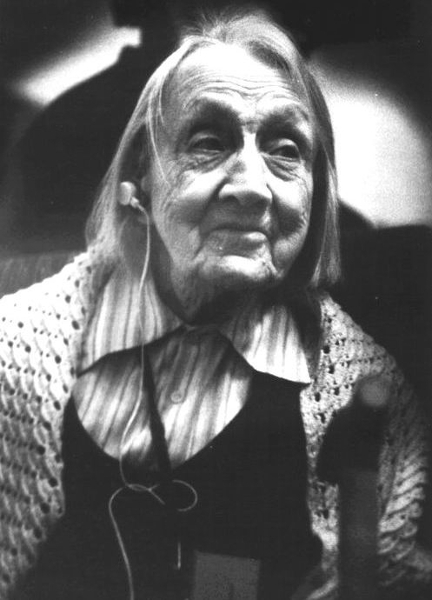

If you do a Google search for Anastasia Tsvetaeva you’ll immediately see a reference to Anastasia G. Tsvetaeva, actress. To the film star who is rumored to be a remote kin of the great poetess, several Internet pages are devoted. Anastasia I. Tsvetaeva can be found if you add her patronymic “Ivanovna” or write the word “sister” beside. “My twin”, “my inseparable one”, Marina referred to her. Russia’s oldest writer who nearly lived until her 100th birthday would have turn 120 years on September 27. “The Last Ray of the Silver Age” shines on us through the lines of her amazing memoirs even today.

If you do a Google search for Anastasia Tsvetaeva you’ll immediately see a reference to Anastasia G. Tsvetaeva, actress. To the film star who is rumored to be a remote kin of the great poetess, several Internet pages are devoted. Anastasia I. Tsvetaeva can be found if you add her patronymic “Ivanovna” or write the word “sister” beside. “My twin”, “my inseparable one”, Marina referred to her. Russia’s oldest writer who nearly lived until her 100th birthday would have turn 120 years on September 27. “The Last Ray of the Silver Age” shines on us through the lines of her amazing memoirs even today.

She could not be measured by a common yardstick, so it’s impossible to write an ordinary article about her. We have numerous recollections about Anastasia Tsvetaeva, not so much from her peers as rather from people younger than her by a couple of generations. She was never a fuddy-duddy, made friends with many, was an outgoing person without complexes. For example, poetess Tatiana Smertina recalled how long she was chatting with some unknown elderly woman, waiting for her royalty at the Fiction Books publishing house. Two hours flew by almost unnoticed, the new friends made jokes about the miserable standing of poets who would never have all dues paid to them… And finally a frowning cashier appeared. Seeing an elderly author and her name in the list, she bristled: “My Lord! Why do you write under this name? You may bear this name but should not write under it! There is only one Tsvetaeva.” One could expect any reaction from the old lady to this insulting remark, but she only smiled back: “What a fervent advocate! But I am Marina’s sister so I can do it.”

When I was a teenager and just developed interest in poetry, composer Gleb Sidelnikov suggested that I should meet Anastasia. “She is 95 and she still full of vigor and enthusiasm! An absolutely clear mind,” he admired. For some reason I did not meet her… Now I can recall about that omission only as a “could have”. Tsvetaeva never waited for a proper occasion – she was constantly communicating with people, observing them, putting down her notes. A legendary personality, she wrote numerous sketches not only about Marina but also about the society they mixed in: writers P. Romanov, I. Rukavishnikov, M. Shaginyan, P. Antokolsky, A. Gertsyk and many others. It is largely through her efforts that the Marina Tsvetaeva Museum opened in Moscow.

After her story Smoke, Smoke, Smoke… saw light in 1914, the 20-year-old writer was approached by people she never met, who asked her: “How shall we live?” Already after the revolution, which provided an answer to this question for many, Anastasia became a member of the Writers’ Union at the recommendation of M. Gershenzon and N. Berdyaev. Soon she wrote her Hungry Epic, where she gathered the statements of different people about the recent famine. Yet this book was never published. She could not enlist the support of reputable Gorky whom she saw in Sorrento. He thought the writer was “late” with her book, since they were preparing to introduce bread cards in the USSR and so recollections about the hungry times were no longer relevant. Later she was denied the publication of her novel SOS or the Constellation of Scorpio. The writer was proposed “to straighten out the fates of her characters making them more optimistic”. She responded to that suggestion: “It’s the same as demanding from Hamsun to make a happy end in his Pan. Victoria and get rid of all tragic elements. Preposterous!” Her only publication in Soviet times was her book about Gorky. The absurdity continued, nonetheless. First she was arrested in 1933, but thanks to the intercession of Gorky and Pasternak, was released two months later. And then came the year 1937 – the height of Stalin’s paranoia. When she was arrested for the second time, the investigator told her: “Gorky is no longer alive and nobody will help you.” Her fairy-tales, stories and novellas were almost completely destroyed by NKVD and even that very book about Gorky (which she later restored by memory). Anastasia Tsvetaeva was sentenced to ten years in prison without the right of correspondence for being a Rosicrucian mystic, but officially on the allegation of counter-revolution propaganda and agitation and membership in a counter-revolution organization. Her son, talented architect Andrei Trukhachev was also arrested for counter-revolution propaganda. What was so disgusting in Anastasia and her son for the Soviet power? She was never interested in politics, being entirely focused on creativity. Andrei was a young and promising architect. Probably her failure to tow the party line and the lack of piety reflected in her books made her politically unreliable in the eyes of Soviet authorities. And her passion for Rosicrucian mysticism under the supervision of archeologist, historian and mystic Boris M. Zubakin, who was later murdered in Stalin’s Gulag, fanned the flames of persecution.

Who knows, maybe the Gulag saved Anastasia from perdition during WWII? But you won’t wish such salvation even on your enemy. Nevertheless, this was not the end of her travails. Two years later Tsvetaeva was sentenced to exile in the Novosibirsk region. She was set free only after Stalin’s death, but was not in a hurry to leave Siberia… Having developed warm affection for the place of her settlement, she wrote My Siberia, a diary. Anastasia warmly recalled the days of her exile, when she lived in a small log hut in the village of Pikhtovka… In the late 1950s she finally left for Salavat to see her son Andrei who had also been released by that time.

Ten years before her long incarceration, in 1927 she saw Marina in Paris. That was their last meeting. And in August 1941 the prophesy Anastasia had made prior to the October revolution came to pass: “Marina’s death will be the most pungent woe of my life.” Anastasia started writing poems in the camp, to somehow divert from the monotonous daily routine, in the ill-fated year of 1941. She began writing in English and then switched to Russian. “The flow of verses filled my days in prison (verses born into the air and enshrined in memory, since even a pencil was forbidden in Soviet jails)”, she wrote in her Recollections. Poetry went on flowing in the camp where she could write with a pencil. To conceal her exercises from curious eyes, she translated her poems into Russian and then into English again, with transliteration. Her texts were taken for preparations for English lessons, as she taught English to convicts and civilian staff. From her exile Tsvetaeva sent her semi-biopic novel Amor written on tissue-paper. The news of her sister’s death reached Anastasia two years after that tragedy – her loved ones had succeeded in concealing the sad event from her for a time.

What a shock must that ordeal be for the person brought up in an aristocratic family! Her mother Maria Mein was a student of Nikolai Rubinstein, an exalted admirer of romanticism and chivalry. She adored her children with a sacrificial love and put up her entire life on the altar of art. Her father Ivan V. Tsvetaev was philologist and art critic who later directed the Rumyantsev Museum and founded the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts. This family reared four children – two were born in the first marriage of Ivan and two daughters, Marina and Asya (that’s how her loved ones called her) were born by Maria. The sisters recollected that their father and mother lived two parallel lives. “What a joy it was to be born from such a strong, noble and unselfish man as our father and from such a tragic and valorous woman as our mother!” – said the younger daughter. During her entire lifetime Maria was in love with another man who had his own family and she was in love with music which was denied her by her father who did not want his daughter to be a musician. Ivan lived by the memories of his first wife who died at an early age and by his art hunting passion. Maria tried to win his favor and was the art advocate. Unfortunately she did not live long enough to see the famous Pushkin Museum finally thrusting its doors open. She died of tuberculosis at the age of 38. The girls did not inherit their Mom’s adoration of music and their Dad’s veneration of fine arts, though they most likely had some painting skills. We have no information about Marina’s painting exercises, but the drawing talent definitely helped Anastasia in her exile, when on demand of the bosses she drew 900 portraits of convicts. Both girls adored literature and poetry. Marina started writing at the age of six and not only in Russian, but also in French and German, so that her father was even a bit concerned: what will happen later? Their house was always full of music – having failed to become a concert-giving pianist, Mom made up for her passion at home. She was very talented indeed. Marina probably inherited her expression while Anastasia – her love and sacrificial service.

Long before growing old Anastasia diligently cared for her health: she did her morning exercise, took cold showers on a daily basis and propagated the breathing gymnastics of Strelnikova. “As a Christian believer, she kept church fasts and from the age of 27 she never ate animal meat at all. Since the same time she forbade herself wine, smoking and other secular temptations. This was her vow and she never broke it, except in the labor camp, after a hard work from morning till evening at the construction site she occasionally smoked one or two cigarettes at the estimate and design bureau just to brace up for a discussion…” recalled her literary secretary Stanislav Aydinyan. The man who was near Anastasia Tsvetaeva her last 10 years knew her better than others. “Anastasia was a self-sufficient woman. She realized that she was not a genius, but just a talented person. Till the end of her days Anastasia remembered her sister as a very dear person, but she did not idolize her. She just had a deep, sincere and personal understanding of Marina’s life and poetry. Some poems of her older sister came down to us only thanks to her memory…”

Why did Anastasia Tsvetaeva sink so deep into the hearts of her contemporaries and descendants? She was surely a “walking history”, a role model of tolerance and kindness. But she also had her special creative gift, being a memoir writer of genius. After reading her Recollections Pasternak wrote to her: “Asya, my soul, bravo, bravo! Just received and read the sequel. Tears were running down my cheeks as I was reading it. This is all written with the language of your heart and you can almost physically sense the passion and heat of those days! However high I ranked you, or loved you, I did not expect such terseness and power of expression… Your style and turn of phrase has the power of conversion…” Marina became a classic of poetry and Anastasia – a classic of Russian memoir literature.

Almost half a century has lapsed since that ill-fated August day, when Marina committed a suicide. Anastasia was a devout person and knew that the church has no forgiveness for those who take their own lives. And yet the last rites were served, even if half a century after Marina’s death. Anastasia with a group of believers and Deacon Andrei Kuraev submitted a petition to hold a funeral service, and it was granted as an exception by the ruling bishop. Patriarch Alexy II gave his blessing, given that Tsvetaeva sisters are a very special case. They reunited again, albeit on different sides of human existence. Anastasia Tsvetaeva willed to her descendants: “Wherever the destiny brings you, shining ball or the rustic seclusion, lavish generously and boldly, all the treasures of your soul”.

Anna Genova

If you do a Google search for Anastasia Tsvetaeva you’ll immediately see a reference to Anastasia G. Tsvetaeva, actress. To the film star who is rumored to be a remote kin of the great poetess, several Internet pages are devoted. Anastasia I. Tsvetaeva can be found if you add her patronymic “Ivanovna” or write the word “sister” beside. “My twin”, “my inseparable one”, Marina referred to her. Russia’s oldest writer who nearly lived until her 100th birthday would have turn 120 years on September 27. “The Last Ray of the Silver Age” shines on us through the lines of her amazing memoirs even today.

If you do a Google search for Anastasia Tsvetaeva you’ll immediately see a reference to Anastasia G. Tsvetaeva, actress. To the film star who is rumored to be a remote kin of the great poetess, several Internet pages are devoted. Anastasia I. Tsvetaeva can be found if you add her patronymic “Ivanovna” or write the word “sister” beside. “My twin”, “my inseparable one”, Marina referred to her. Russia’s oldest writer who nearly lived until her 100th birthday would have turn 120 years on September 27. “The Last Ray of the Silver Age” shines on us through the lines of her amazing memoirs even today.