![]() — Russkiy Mir Foundation — Journal — Articles — Captain without a Ship

— Russkiy Mir Foundation — Journal — Articles — Captain without a Ship

Captain without a Ship

Captain without a Ship

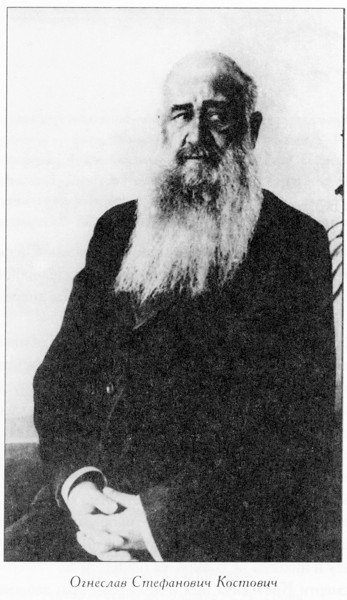

In the summer of 1878 a new resident moved into an apartment building on Troitskaya Ulitsa in St. Petersburg. He was tall and broad-shouldered, boasting an enormous black beard and matching eye-patch. He introduced himself in broken Russian as a captain of the Russian navy. But he much better resembled a pirate! His name was Ogneslav Kostovich, but in Russia he was called Ignaty.

It’s hard to say whether this man of rather exotic appearances was particularly charismatic. No such descriptions of him remain. But what is interesting it the fact that over the course of the several decades the Ignaty Kostovich lived in Russia, he successfully worked his way into offices of the highest level, places inaccessible to the ordinary mortal Russian even in his dreams.

The first such place was the office of Grand Prince and heir to the throne Alexander Alexandrovich. The grand prince received a petition by his visitor, the author of four inventions whose realization apparently could not be postponed. And the unusual appearance of the inventor coincided with the uniqueness of his inventions. For example, a hanging parapet, or a traveling kitchen or a steamship speed regulator. The future emperor’s attention was particularly engaged by the inventor’s plan to build a submarine vessel. Ignaty was soon telling the grand prince’s personal aide First Captain Baranov: “The boat is designed to hold eight people and cruise under water for 20 hours at a time, taking on board 12 torpedoes…” All Kostovich was asking was to be provided with workers, materials and a wharf to build his “fish-boat”.

The idea to build a submarine was nothing new. The first recorded drawings seen in Leonardo da Vinci’s notebooks. And three hundred years earlier a British explorer reported underwater craft sewn from seal skins in Greenland. In 1620 a submarine was successful tested in the Thames by Dutch inventor Cornelius Drebbel. The list is quite long and Russia had already tested a few designs of its own by the time Kostovich came along, so why did his idea catch the attention of the grand prince and specialists of the Navy Ministry?

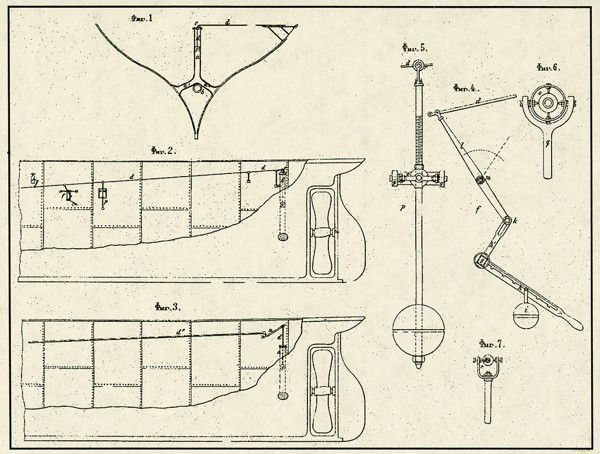

The first try at promoting his idea was a failure. Not even the support of the grand prince held. In 1878 the navy admirals considered the idea to be too “raw”. Kostovich worked over the blueprints and in spring of 1880 presented whole set of documents at the Naval Technical Commission. The inventor guaranteed that vessel of 22.5 m in length, 3.6 m in width and 4.2 m in height with a displacement volume of 180 tons would be capable of submerging to a depth of 45 m and reach speeds of 20 knots when at the surface and 12 knots when submerged. Kostovich announced that the submarine would be driven by a 1000 hp motor, but he failed to satisfy the commission’s curiosity on this account. What kind of motor did he have in mind?

At that time submersible vessels used steam ad pneumatic motors, but achieving the power supposed by Kostovich with such motors was unthinkable. Captain Ignaty let out another secret: the submarine would not use ballast tanks to facilitate immersion and surfacing, but he didn’t let the sea wolves of the navy in on how this process would be regulated. Kostovich said that he would only reveal this secrets if the ministry first agreed to provide funds to build and then purchase the first experimental vessel.

Despite the positive conclusion on the project plan, the admirals were not ready to risk either state funds or their own jobs. Kostovich packed up his blueprints and other drawings, the whereabouts of which are not known to this day.

If we take a look at the inventions of this one-eyed engineer from the later period of his life, and they are more related to the sky than the sea, then we can take a guess at what type of secret motor he had in mind. It seems that he may have been leaning toward an internal combustion engine.

In parallel with the “fish-boat”, he proposed other inventions as well. And much more successful ones at that. While it’s probably not necessary to get into the details of Kostovich’s steamship speed regulator, but he managed to sell his patent to the invention for 10,000 rubles. And he was successful with other projects as well.

Kostovich was a pioneer in inventing “arborite”, which was one of the first plywood products bound with Kostovich’s secret glue. And if we note that plywood doesn’t get much respect these days, we should remember that only 30 years following Kostovich’s invention, this material was used by the great Russian airplane engineer Sikorsky to create the largest airplane of his day – the Ilya Muromets.

This plywood was needed for one of Ignaty’s important projects. It was only discovered later, after a number of inventions and devices failed to meet expectations, that one could make a good living off of such glued sheets of wood. A plant owned by Kostovich outside Petersburg created various pipes, trunks, barrels and boxes. This new product was in great demand, as it was not only sturdy but it was also inexpensive. Kostovich’s arborite was made of aspen, a tree not highly valued in Russia during the day. But Ignaty was interested in money only so far in that it was necessary for him to realize his projects.

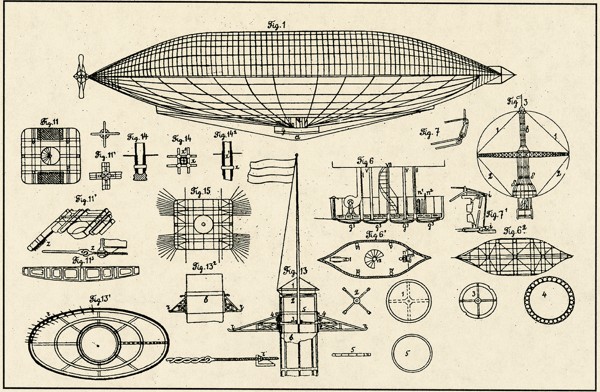

In 1879 the journal Aeronaut (Воздухоплаватель) announced that it was calling a meeting of enthusiasts headed by Kostovich in order to start building an airship of the likes that had never been seen before on earth. The group met and immediately decided on the name for the ship 0 Rossiya! [Russia]

In 1881 Kostovich announced that before the entire country what kind of bird he was planning to put in the sky. According to the blueprints the dirigible appeared as follows: 65 m long, 12 m in diameter. The motor was to be an engine based on a smaller model that he had already tried out on a boat of his own making. But this motor was to be 80 hp. Interestingly, at that time experiments were taking place everywhere on internal combustion engines. In Germany for example, there were engineers whose surnames, unlike Kostovich, are known throughout the world today – like Daimler and Benz. However, none of these were suggesting the use of petro as a fuel and electricity to spark the combustion.

The initial funds for the construction of the Rossiya dirigible were collected via a joint stock company. And once those funds ran out he turned to the Military Ministry. The military brass took a liking to the project and decided to support it. They weren’t even concerned by the fact that Kostovich insisted on using a petrol-powered motor.

In 1888 Kostovich received a patent for the invention of an internal combustion engine in Britain and the United States. However, only one example of his engine has survived to this day. It is preserved in the Air Force Museum in the town on Monino in the Moscow region. The engine weighs 240 kilograms, and that is without the fuel injection component and cooler.

The dirigible project proceeded slowly. In 1889, when the motor and parts of the body were prepared, the project was in need of one final injection of funds to complete the assembly – 40,000 rubles. This time the military turned Kostovich down. And to make matters worse, some of the parts went up in flames when the storage hangar caught fire.

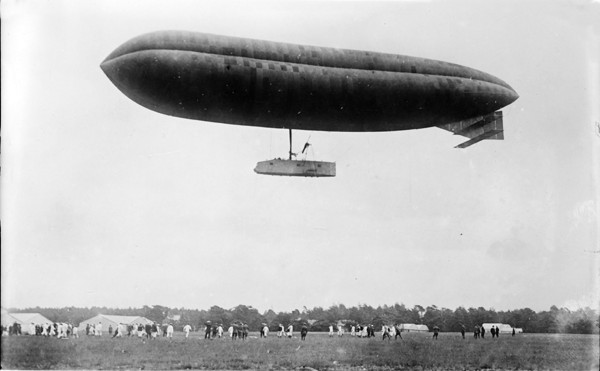

Broken down in components, the Rossiya dirigible lay forgotten in storage for 20 years. And when it was finally rediscovered, it was already too late: Zeppelin ruled the sky and, more importantly, the airplane era had begun.

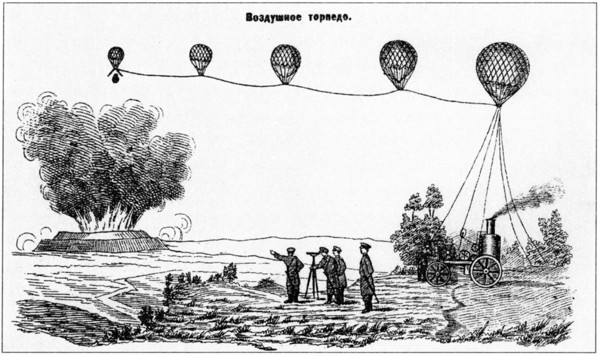

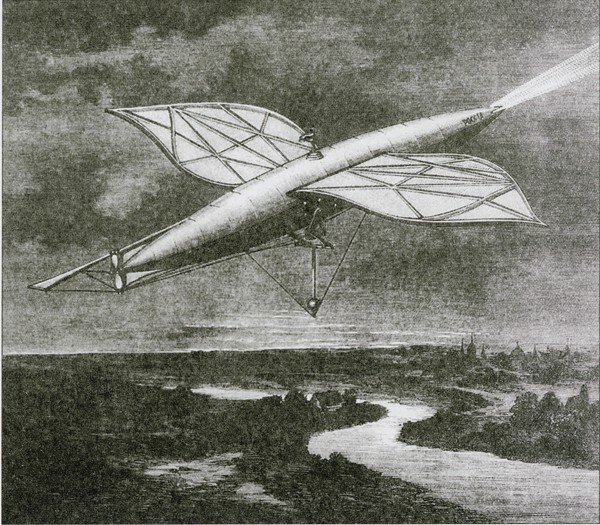

But Kostovich did simply sit on his hands those 20 years. He invented a stratostats, various machinery, air telegraphs, hydroplanes…

In 1912 a woman appeared in St. Petersburg by the name of Maria, Kostovich’s daughter from his first wife. She came from Belgrade with one goal in mind – to convince her father to return to Serbia.

Back in 1848 a boy was born to the Kostovich family, a family noble Serbs living in Pest (Hungary). He was christened Ogneslav. His father Stefan was the owner of ships traveling the Danube. Following his studies, the boy’s fate was already decided – he began navigating his father’s boats along this most famous river of Europe. And it could have continued on like this until the end of his days, if it weren’t for the Russo-Turkish War in the Balkans. His father sold two ships to the Russian army, as they were necessary to fight the Turks on the Danube. Although the Austro-Hungarian authorities discouraged contact with the Russians, the Serbian family of Kostovich was eager to lend a hand, with Ogneslav taking the helm of one of the ships sold to the Russians. But this trip down the Danube turned out to be a long one. He fell captive to the Turks at Vidin fortress and was badly wounded in the head, which resulted in the loss of his eye. Later, having made it through to the Russian, he decided to stay with them and travel on to St. Petersburg.

Despite having made a name for himself and registering a large number of patents, Kostovich remained to end a subject of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Whenever asked about this, he always said that he hadn’t enough time for such matters: “I’m Slavic in body and soul! I’m a Russian captain, can’t you see?”

And Ignaty did not return to Serbia with his daughter. He remained in Russia, where he died and was buried on the eve of the Revolution.

Sources: Chernenko G.T., The Life and Unusual Adventures of Captain Kostovich; materials from the Russian State Archive of the Navy and State Historical Museum

Author: Mikhail Bykov