![]() — Russkiy Mir Foundation — Journal — Articles — The Hussar’s Cross

— Russkiy Mir Foundation — Journal — Articles — The Hussar’s Cross

The Hussar’s Cross

The Hussar’s Cross

Twelve Chairs by Ilf and Petrov has a chapter titled The Story of the Schema-Hussar. Its hero, Count Alexei Bulanov, is of aristocratic origins; a fire-eater and reveler who has frightened the entire high society of St. Petersburg. And then we see that he is a traveler who has returned from Abyssinia with an Ethiopian boy named Vaska. Later, now a hermit monk, character has an accidental encounter with some rather shady-looking people in leather jackets hauling wooden Mauser boxes…

It seems that this is only a fantasy, a collective image, to a certain degree a parody of the new Bolshevik order and those who decided to hide from it in the catacombs of faith. But no. This story is quite real. Of course, here it is spoiled by this literary tandem’s cynicism and also enriched with the claptrap humor peculiar to the post-revolutionary period. But it is based in fact.

So who was he, this Count Alexei Bulanov? Was there once such a crazy hussar? Did he really travel to Ethiopia? Where did that curly haired boy Vaska come from? In what sort of monastic cell did the reveling count find his peace?

On September 26, 1870, a boy was born and christened Alexander. He had Russian, French, Georgian and Tatar blood running through his veins. And, as was expected in most Russian noble families, the boy had a career in the military to look forward to. And although Alexander received his basic education at the Imperial Alexander Lyceum, the very same one attended by another famous Alexander – Pushkin – this graduate preferred not to go into the civil service as a titular counselor in the chancellery but rather join the renowned Hussar Leib Guard regiment, signing up as a volunteer. Within 15 months, in 1892, he earned the rank of cornet.

The Leib Hussar served as was becoming and was not known for partaking in the usual hussar pastimes. Thanks to his riding and fighting skills, he was sent to fencing school and later returned to his regiment as head of the training team.

In 1896 the Russian Red Cross began forming two groups to send to Ethiopia. For 20 years running a colonial war had been going on there between the Italians and local tribes, who had united behind Negus Menelek II. What did Russia have to do with this, you might ask? As it turned out a substantial portion of the local population were of the Orthodox confession. And there could be no more serious a reason for the Russian volunteers.

Our hero, for his superior discipline and severity, received the nickname Mazepa. It’s not quite clear why this exemplary cavalryman would take on the nickname of that mad Cossack hetman. But perhaps it had to do with the fact that he hailed from the Sumy region in southern Russia.

With Mazepa’s peculiar thoroughness, he prepared for his next stage. He even learned Aramaic with the help of Professor Bolotov at the Spiritual Academy in St. Petersburg.

During the first expedition, the hussar cornet should have died at least three times: when traveling through the wild expanses between the port in Djibouti to the city of Harar; in the Danakil Desert, where he was attacked by nomads and left to die of thirst; and during an elephant hunt organized by Menelek.

But everything turned out fine. He returned to St. Petersburg and received the rank of lieutenant as well as the Order of St. Anna of the 3rd degree. In a half a year’s time, our hussar once again made plans for Africa – this time as a part of a diplomatic mission to reach an agreement between the Russian Empire and Ethiopia. But in lieu of diplomatic fanfare, he was thrust into the army. Menelek sent him to be a military advisor during the campaign for Kaffa, into lands which no European had seen before. And there transpired a one of the most sentimental stories in the life of the Russian officer.

The camp was situated on the bank of Lake Rudolf. The locals brought a bloodied young boy who was dying from hunger to the lieutenant’s tent. The hussar washed the boys wounds himself and then cared for the patient. And after the boy got better, despite the predictions of death from all the witch doctors in Menelek’s service, he named the boy Vaska.

In honor of this event, the Russian officer named one of the hills on the lake shore after the boy. And apparently it still goes by this name – Cape Vaska. Later in Russia he was on numerous occasions asked why he called the boy Vaska. To which he simply shrugged his shoulders and said: “God knows why!”

During the second expedition he twice escaped inevitable death. On the banks of Lake Rudolf he caught a dangerous fever. And then during one of the scouting operation, he wound up unarmed and surrounded by savage local tribesmen, but he was saved in the nick of time by a sharpshooting Ethiopian officer.

During his long expedition, he not only fought masterfully but also devoted time to studying East Africa. Upon returning to St. Petersburg he received his next promotion, next order – Order of Stanislav of the 2nd degree – and even the Semyonov-Tyan-Shansky Silver Medal from the Russian Imperial Geographical Society for his contribution to science.

His third mission to Ethiopia was not long in coming. He had a private conversation with Tsar Nikolai II on the subject and Foreign Minister Count Muraviev instructed him not only to study the geography of the country but analyze the political situation as well.

His mission lasted nearly a year. On the trip back the Leib Guard hussar made a stop in Jerusalem, where he took his monastic vows – leaving the military service to serve God. At least that’s what they wrote in the newspapers.

Nonetheless, he did not immediately succeed in fulfilling his vows. Following his service in Ethiopia, he headed off to China as a volunteer to help put down the Boxer Rebellion, which he did. In doing so he received the rank of cavalry captain and two more orders: St. Anna of the 2nd degree and St. Vladimir of the 4th degree. In short order came recognition from Paris – the National Order of the Legion of Honor.

It would seem that he could just go on serving and serving, having already attained the rank of cavalry captain (practically a colonel) and chest full of medals. But nonetheless, Alexander resigned from service in 1903. The formal reason given for his retirement was poor health, which had resulted from his numerous expeditions and battles.

But back in 1894, when still the rank of a cornet, our hero made acquaintances with Father (and posthumously Saint) John of Kronstadt. So it seems that his vows taken during his visit to the Holy Land were no coincidence. It is known that throughout his entire military career Alexander kept with him a portrait to this revered priest.

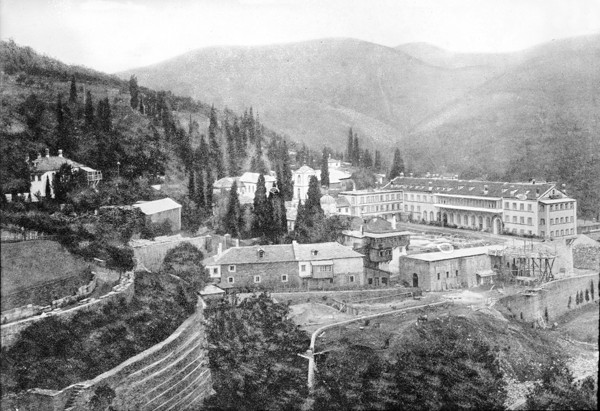

In 1903 the novice arrived at the Vasheozersky Monastery. Later a group of seven – the former cavalry captain and six hussars from his regiment – departed for the Holy Mountain – Mount Athos. In 1907 the officer took on the vestments of a monk and the name Antony.

A year later Father Antony once again turned up in Ethiopia. He went to see Vaska and also his old companion Emperor Menelek. However, his main mission was a failure: he did not receive permission to set up a monastic colony together with the other Hussar monks in Ethiopia.

The monks returned to Athos where Father Antony headed the Imiaslavie movement. That is how the Russian Orthodox Church dubbed those who together with Father Antony took up the belief that “the name of God is God himself”. The Orthodox Church dealt severely with these outcasts, calling it a heresy. The adherents of Imiaslavie were taken back to Russia under military convoy. They would have been put on trial had Tsar Nikolai II not stepped in on Father Antony’s behalf.

Despite the risk of excommunication, Father Antony tried to organize a polemic around Imiaslavie. However, 1914 had come and with it war. Father Antony joined Russian forces, but this time as a chaplain. There are reports that he not only prayed for the forces before battle but also energetically led them into attack.

It is not known when exactly Father Antony left the front for his family estate in Lutsikovka near Sumy. But it is known that in 1919 bandits attacked his house and Father Antony was killed in the rampage.

In the secular world this surprising person was called Alexander Ksaverievich Bulatovich, and not Count Alexei Bulanov. Although there are some similarities…

Author: Mikhail Bykov