![]() — Russkiy Mir Foundation — Journal — Articles — A Strange Land

— Russkiy Mir Foundation — Journal — Articles — A Strange Land

A Strange Land

A Strange Land

In late August 1914 Georgy Sedov’s expedition set out for the North Pole. Little is known about Nikolai Pinegin, who planned the expedition – an artist, Arctic researcher, writer and author of the first documentary about the Arctic. This May he would have turned 130. We managed to find the grandniece of Nikolai Pinegin – Svetlana Skachkova, who shared some previously unknown facts about the life of her famous relative.

In the Moscow apartment of MSU Professor Svetlana Skachkova everything pointed to the fact that the family is closely linked with traveling and seafaring. The walls are covered with reproductions of Aivazovsky's paintings, with a Navy banner from the Northern Fleet's boats hanging in one of the corners. Svetlana's grandfather was a cousin of Nikolai Pinegin. He was 15 years younger, treasured Nikolai's friendship and heeded his advice. It is following the advice of his older cousin that he took his family and moved to northern latitudes beyond the Arctic Circle where he started building a military airfield and then laid the first stone of Salekhard. Svetlana's father Alexander Rodionov was commodore and commander of the testing hydro-acoustic facility of the Northern Fleet and served on four of Russia’s fleets. His two brothers voyaged in the Arctic seas too: commodore Anatoly is now professor and director of St. Petersburg Oceanology Institute's division, and Vladislav was also commodore and professor. The entire family visited those sites on the Kola Peninsula beyond the Arctic Circle, which were described by their famous kinsman... The professor's home library includes a valuable archive: photographs of Nikolai's parents, sisters and children, photographs from the expeditions of the polar researcher, sketches and drafts of articles with Pinegin's notes. He was too modest to write a lot about himself and his only biography was published in 2009 by Andrei Ivanov, a historian from Yelabuga whence Pinegin came.

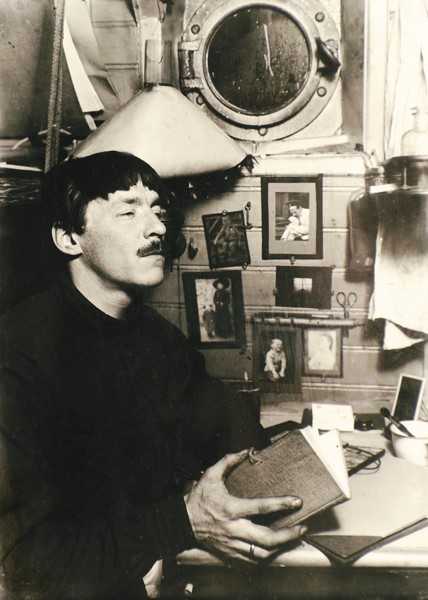

Svetlana Skachkova was thumbing the photo album – landscapes, ships, ports, sailors of the 19th century – plunging us into this amazing period in history, when people sacrificed their lives for the sake of filling blank spots on maps and the Arctic was shrouded in mysteries, fearful legends, life-threatening dangers and seemed to be beyond the human reach. Here is how Nikolai Pinegin described the pioneer's daily routine in his book Amidst the Icefields based on diary entries of the expedition to the Arctic Pole of 1912-1914: "Yesterday we were dragging ourselves along the knee-high snowdrifts, occasionally falling down between hummocks up to our waists. Our feet bogged in cracks, we were sliding over ice ridges and fell down again and again. But we got up on our feet and walked stubbornly into the furious blizzard, the horrible dazzling snowfall... Sweating, with uncontrollable swearing on our lips and minds, we strained ourselves as we pushed along our dog-sled stuck all over with snow. We lifted scourges, our arms shaking from strain, and lashed the amiable, diligent dogs, muffling our compassion for these reeling creatures with brutal yelling. We could not get rid of our hypnotizing dream to lie down and stretch out our legs..."

Dreaming about the north

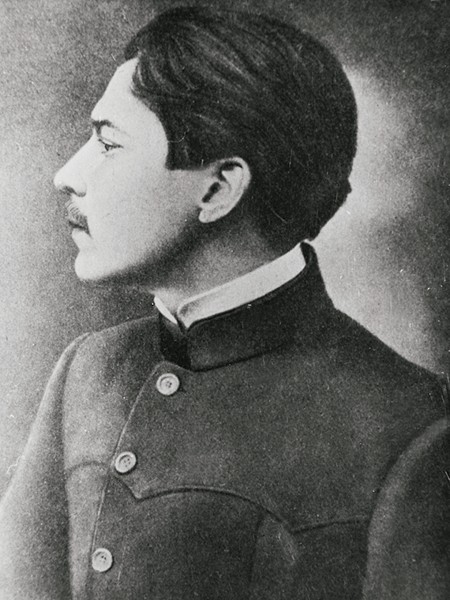

Nikolai Pinegin was born on May 10, 1883, into a veterinarian's family. When the boy turned 10, his mother died and his father with three kids on hand married again and his new wife bore him four girls. These changes were hard on the boy and his two sisters. The domestic worries took a toll on his academic progress: the boy was expelled from the fifth grade of the Perm Gymnasium for his refusal to attend church liturgies. In his spare time the boy drew a lot of pictures. "There is a legend in our family that the Pinegins were relatives of the great Russian painter Ivan Shishkin who also came from Yelabuga," says Ms Skachkova. "The Pinegins asked Shishkin to give several lessons to Nikolai, but this did not work out."

In 1900 the youth left home at the age of 17, set out for Kazan and enrolled in an art school. In those years he started dreaming about the Arctic. "There was a well-known artist named Alexander Borisov who painted the North using unusually bright colors," says Svetlana. "Pinegin said he did not see truth in Borisov's works and would rather depict the North as it is. While yet a student of the art school, he planned his first expedition to the land of snow and ice."

Nikolai Pinegin did his best to set some money aside for his first expedition: he painted portraits for money, played in the brass band, traveled with buskers and saved on everything, feeding on bread, herring and tea. With two of his friends he planned to set out from Kazan over the Northern Dvina River to examine the North-Catherine Canal – a waterway from the river Kama to the Arctic. Construction on this 19-km-long canal was launched in 1785 at the decree of Catherine the Great. In 1822 it was inaugurated, but navigation over it had continued only until 1847, when a new waterway appeared. The young guys applied to the Imperial Russian Geographic Society for financial and academic aid. In a return letter they were assured of the Geographic Society's patronage and... offered to buy a map in the nearest shop. No funds were disbursed, but that circumstance did not alter the plans of the young travelers. However strange this might seem, not only did the Geographic Society's certificate serve them well; it saved their lives, when locals residing not far from the North-Catherine Canal were going to make short shrift of the boys, having decided that they were carrying boxes with gold bullions. Trouble came to the expedition's participants from another side: one of the youths was badly wounded in his arm because of rifle mishap; that was the end of their travel. Years went by but Nikolai Pinegin still dreamed of the North, gaining experience and moonlighting where he could. In 1906-1907 he served as draftsman at the East-Chinese Railroad and later as a land-surveyor in Saratov. Yet every night he avidly read stories about the permafrost region and northern lands.

In his soul he treasured the dream to show the real North to the world. In 1907 he entered the St. Petersburg Academy of Fine Arts and by 1910 he finally managed to set aside enough money for traveling from Arkhangelsk to Novaya Zemlaya. Nikolai perceived the long-awaited North as a prehistoric land. This is what he says in his essay Iceman's Notes: "What a strange land! You won't see green color in its vast expanses – only gray slate, shingles and pale lifeless color under your feet and all over. Everywhere there are bare stones, brittle shingles and cracked mud. At first glance it appears that the earth is bare like in prehistoric eras, when it was divided into dry land and the sea and when no organic life had yet been born." In Novaya Zemlya Pinegin painted those sketches that were a great success at the autumn exhibition in St. Petersburg. But the main thing is that in this "strange land" the painter met Georgy Sedov and that marked a decisive turn in his life. Two years after his wedding Georgy Sedov helmed a hydrographical expedition to examine Krestovaya Guba and was on board of the same ship with Nikolai Pinegin, bound for Novaya Zemlya. Their acquaintance grew into a friendship and there, in the midst of snow and ice, they agreed to go to the Arctic Pole together.

Stain in the middle of the crown

The expedition was prepared in a rush. On December 14, 1911, Roald Amundsen reached the South Pole. Fearing that the Norwegian would discover the North Pole as well, officer of the Hydrographic Administration Georgy Sedov applied for a leave on the following ground: "Amundsen wishes to win for Norway the honor of discovering the North Pole, but we'll travel there this year and prove to the entire world that Russians are also capable of exploits." Americans Frederick Cook and Robert Peary also sought to conquer the North Pole.

The Russian elite thought that Sedov's initiative was nothing but recklessness. Donations for this undertaking were scant. The funding of an expedition to the North Pole failed to pass the State Duma (Sedov asked for 50,000 rubles). Finally, Mikhail Suvorin, co-owner of the newspaper Novoe Vremya, announced through his periodical a special fund-raising campaign in support of the travel and provided 108,000 rubles. Extraordinary excitement rose in society, as ice deserts were discussed both in worldly saloons and at the bazaars. Nicholas II donated 10,000 rubles. "It was then rumored that the largest part of the financing was provided by a certain ballerina from Mariinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg," says Skachkova.

In accordance with the original plan, the expedition was to start from Archangelsk early in July 1912, heading for Franz Josef Land, and its participants planned to winter there exploring the shores, climate and bedrock structure and collecting precious samples. Georgy Sedov intended to set out for the Arctic Pole over drifting ice on dog-drawn sledges and then return either towards their anchored ship or to the northern shores of Greenland.

In July 1912 Sedov managed to buy an old wooden steam-sailing schooner called the Saint Martyr Foka. Its cargo carrying capacity did not allow the crew to take on board all the prepared supplies, so they had to unload some stuff. They did not have enough time to fully repair the vessel and so the captain, assistant captain, navigation officer, mechanic, assistant mechanic and boatswain resigned on the grounds of inadequate preparations of the Foka for the voyage.

Leaping ahead, we can note that even though the old ship occasionally took on water in times of fierce storms, it proved rather sturdy. This cannot be said about other constituents... The Maritime Ministry suddenly annulled the leave of the radio officer employed by Sedov and the expedition was left without communications, so they could not count on calling for help. The suppliers of victuals turned out to be light-fingered and the polar researchers had to eat poorly pickled meat, which in turned provoked scurvy. The sled dogs for which they paid the triple price proved to be common mongrels with the exception of several ordered from Archangelsk in advance. Out of the 22 members of the crew 35-year-old Sedov was most experienced.

The expedition had to cover 1,300 miles. Eventually the journey turned out to be ten times shorter and much more challenging than it appeared in the beginning. They had to set up the first polar station near Pankratyev Island because of impassable icebergs. This meant they did not yet reach Franz Josef Land. During those months the northeastern coast of Novaya Zemlya was described and discrepancies with the previous maps were found. Sedov bypassed the northern extremity of the island on sleds, passing from Pankratyev Peninsula to Cape Zhelaniya. There was a shortage of warm clothes and Sedov was at loggerheads with ship captain Nikolai Zakharov. The results of the research along with the request to send a vessel with coal and dogs to Franz Josef Land were dispatched on June 21 of 1913 with Captain Zakharov and three members of the crew. However the latter disrupted the timeframe for the delivery of the request. The newspapers of the time wrote that the elite naval officer Zakharov did this on purpose, since he could not get lost in the places he knew too well and on fine weather at that. The Arctic explorers did not receive any help. Having arrived in Franz Josef Land in the fall of 1913 the expedition did not find either coal or victuals. Against all the odds they continued their journey. The schooner's steam boilers were fueled with a polar station dismantled on Novaya Zemlya and with walrus fat. In the end they started disassembling their ship. They could not get too far from Franz Josef Land because of foul weather and they stayed for their second winter on Hooker Island. That winter was unprecedentedly cold in the Arctic, with temperatures dropping down to 50 degrees Celsius. They did not use their scanty firewood for heating, but only for cooking meals. People were dying of scurvy. Despite the horrible conditions, they never ceased their research: the researchers and those who could walk observed and monitored life in the Arctic. Pinegin went out to draw sketches, took measurements and hunted.

On February 2, 1914, Georgy Sedov suffering from scurvy took two sailors and set out for the North Pole on dog-drawn sleds. The expedition tragically died. This is how Nikolai Pinegin described in his book the captain's parting with his crew who were aware that this was their last conversation: "Sedov tried to encourage the sick: 'Life is hard, now is the most severe Arctic season, but time goes by. With the next sunrise all of your diseases will be gone. The polar party will get back unharmed and we'll all together return to our homeland as a tight-knit family with a sense of fulfilled duty! I do not want to tell you farewell, but rather good-bye.' Everybody was standing pathetically silent and on the verge of tears. We wished him a happy journey. Sedov died on March 5 near Rudolf Island. "This was surely a deliberate step," says Svetlana. "In the depth of his soul Georgy Sedov understood that they would not be able to reach the North Pole, but they just could not stay behind. As the head of the expedition he could not return in disgrace because of the failed mission."

Staying in the land of ice meant a sure perdition of everybody. "Nikolai Pinegin, as one of Sedov's fellow thinkers, felt moral responsibility for the outcome of the expedition and so he did his best for the ship to be able to sail back to Arkhangelsk. He was a pivot man and informal leader of the expedition," says Ms. Skachkova. "The survivors owed him their lives. He was the best hunter and fresh meat meant a chance for the crew members not to die of scurvy. He had that amazing power of the spirit that lifted the crew from the abyss of despair and did not allow quarrels to fail the entire campaign." This man had a staggering zest for life. Pinegin was the only one who never had scurvy, because in spite of bad weather and queasiness he went out of his cabin every day to work. He painted sketches, tamed polar cubs, did research work, hunted, painted prankish mural newspapers at the time when the crew was gripped with malaise, depression and panic.

His way home was marked with an amazing event. The polar researchers accidentally came across Valerian Albanov in the Arctic ice – navigation officer of the Saint Anna ship from the perished northern expedition of Georgy Brusilov. Saint Anna sailed off in 1912 to storm the North-Eastern pass, but drifting ice carried it far away to the north. On August 29, 1914, the rundown Foka entered the river Rynda of the Murmansk region. A week later the travelers arrived in Archangelsk by a ship sailing to the same destination. There they found out that a war was going on, everything had changed in their country, and nobody was waiting for them.

Help us while it's not too late

On coming back home Nikolai Pinegin continued his studies at the Academy of Arts and graduated from it in 1916. He taught the art of drawing at Stieglitz Art School. This was wartime and he found a job of historiographer and painter at the Historical Corps of the Black Sea Fleet. To prepare for the spring vernissage at the Academy of Arts, he took a leave and left for St. Petersburg. At the vernissage in 1917 he was honored with Kuindzhi Prize for his painting The Polar Rest. Yet the joy did not last long. At the height of the exposition the February Revolution broke out and Pinegin was elected as a representative at the first of workers, peasants and soldier congress.

His leave ended and he returned to his service at the Black Sea Fleet and was placed in charge of the art studio in Simferopol. During the Civil war the Simferopol studio was disbanded, with Red and White governments quickly replacing each other. During this time Nikolai Pinegin had to shoot documentaries about the military campaign at Perekop. He had nothing to subsist on and no opportunity to return to his family in St. Petersburg, no information about what was going on, and Pinegin started looking for opportunities to emigrate. Help came from his friend and writer Georgy Grebenschikov, who wrote a letter to the Chief of Foreign Relations Administration of Wrangel's government in the Crimea Peter Struve with the request to help them leave the Crimea for Paris. The letter contained the following lines: "We decided to make our way to Paris through heroic endeavors, down to making our living by menial labor; this is exactly what I've been doing during four months; in particular I am engaged in cabbing and journey-work"; "I would rather not look for strong words to let you know how offended we are by the awareness that as rare workers of culture we do not receive any backing from the government"; "help us while it's not too late. Answer me, please, and call Pinegin to your office for a conversation."

Struve responded and sent a telegram via Constantinople to Ambassador of the Interim Government to France who was in charge of refugees from Russia. Pinegin arrived in Constantinople in October 1920, but was denied the French visa and got stuck there for almost a year, moonlighting as a porter, drawing signboards and working as a tourist guide over Byzantine monuments. Later he set out for Prague, not Paris, where he was commissioned to create scenery for the opera Boris Godunov.

In spring of 1922 he had a meeting in Berlin with Maxim Gorky who recommended him to write about the North and helped him publish the book Amidst the Icefields. Pinegin was invited to deliver lectures on the Arctic. During this time the polar explorer drew close to Alexei Tolstoy with whom they were looking for the opportunity to return to the USSR. They did that in 1923, thanks to Maxim Gorky who intervened on their behalf.

In his homeland Nikolai Pinegin continued exploring the Arctic. In 1924 he worked as an observer in aero reconnaissance. In 1927 the Academy of Sciences in the USSR commissioned Pinegin with building on the New Siberian Islands (Lyakhovsky Islands) a permanent geophysical monitoring station. It took him one year and a half to build it. “At this time, in the words of Sasha Pinegin, one of Nikolai’s grandsons, Stalin issued an informal decree to forget Pinegin’s name and to focus on Ivan Papanin,” says Svetlana. “For Papanin was a Soviet hero and Pinegin was a hero of Imperial Russia. This is why Pinegin hurried to return from Lyakhovsky Islands in February, when even locals seldom make long-distance travels. Yet he had to get back on dog sleds, froze his lungs, and then fell sick often, which ended up killing him.”

In 1930 he tackled the task of establishing the Museum of the Arctic in Leningrad, which is currently the world's largest museum on this subject, with about 100,000 exhibits including Pinegin's paintings, to be sure. He was engaged in promotion of the Arctic, writing books and articles, joining the first tourist expedition to the Arctic Pole organized by Intourist. In 1932 he helmed an expedition to Rudolf Island within the framework of the Second International Polar Year. Built during that travel was a meteorological radio station that had long been considered the world's northernmost station. From 1931 to 1934 he was editor of The Arctic Institute Bulletin and published a book about Brusilov's expedition, based on his diaries. In 1937 he brought 19 boxes with films shot during the expedition of 1912-14 to Leningrad's Museum of the Arctic: polar poppies, seals, walruses, birds... Nobody knows the number of canvases painted by Pinegin: many of them were purchased by private art hunters or given away. "Nikolai often presented his works as gifts," says Svetlana Skachkova. "One day he painted a large canvas titled Sweet Dream that depicted bears sleeping on the snow between ice ridges. Polar researchers who visited him asked him to sell the painting, but he simply gave it to them. In order to survive, Nikolai often brought his paintings to a specialized shop of the Union of Artists on Nevsky Avenue. He also presented several of his pictures to Maxim Gorky. Nikolai repeatedly visited him in the Crimea and in Leningrad. Gorky had a large gallery where various gifts were put up for show: vases, paintings and poem drafts on sheets of paper. The paintings presented by Pinegin were also displayed in this gallery and later landed abroad, though some of them returned to the Museum of the Arctic and Antarctic."

The party bosses supervising the Institute of the Arctic were suspicious of Pinegin's intentions and one day decided to exile him to Kazakhstan, having remembered his emigration. Writer Konstantin Fedin and Professor Vladimir Vize intervened on his behalf and after several months in exile Pinegin was set free, although this incident would continue to tarnish his name.

Genuine polar night

The personal life of Nikolai Pinegin was never highlighted. Ms Skachkova told us that he was married twice. "His first wife Alevtina was a modern woman for her time, unfettered so to say by the revolution, looked nice but smoked a lot," said Svetlana. "They had three children: daughter Tanya and two sons Yuri and Dasy. While their father was traveling over the north, his kids resided in a boarding school." Svetlana did not know much about Alevtina, but met her grandson Alexander. Dasy worked as a mine foreman in the Far North. Yuri worked for the Institute of the Arctic, participated in expeditions to the North and his children Dima and Sasha were also brought up at the boarding school. His older son Sasha completed a music school and inherited a passion for traveling and adventures. He got involved in geological explorations, lived a hard life and now is a retired old man. He has a son named Alexander and two granddaughters. Dima who has already died left two daughters and two grandsons.

The story of his second marriage is very romantic. Nikolai twice met his future wife Elena: the first time when she was a student at the Stieglitz School and the second time when he lived in exile in Kazakhstan in 1935. Elena was the granddaughter of a certain St. Petersburg-based tailor who made clothes for tsar's butlers and coachmen. She was educated at the Institute of Noble Maidens established by Princess Theresia von Oldenburg; after the revolution she studied at the art school where Pinegin was teaching at the time. Like many other girls at college, she was in love with the famous teacher. She recollected: "Mr. Nikolai, tall and slender, would enter the classroom in a lope, quickly readjusted his rebellious strand of hair with a damaged finger and after greeting the students would start speaking... Later, watching the fulfillment of various assignments, he tactfully made remarks and corrected the drawings. He seemed inapproachable and we all knew that he loved his wife and his children." In 1935 she was exiled to Kazakhstan because of her noble origin. "Elena told me that she was not initially exiled but sent on a business trip to write essays about the everyday lives of Kazakhs, and she wrote articles for various magazines," says Svetlana. "She came there with her things for 10 days, wrote an essay, and when she was about to leave, the administration informed her that she would stay in Kazakhstan permanently. But where? She had to ask locals for the permission to lodge in their yurts, there were no employment opportunities, horrible misery everywhere. Elena said she made friends with some doggy who brought her bones and with a she-goat whom she milked in secret, surviving as she could." One day Elena went out for a walk under rain and saw... Nikolai Pinegin on the road. He was walking towards her with an easel. "He recognized me," says Elena, "and greeted me very courteously. I did not know what to do, jumped for joy and accidentally splattering him from head to feet in puddle water. He smiled. Since then we started visiting each other and developed a friendship... He saw my hardships and helped as he could. The age difference between us was 18 years." Pinegin lived in the home of an affluent Kazakh family and several months later he was permitted to return with Elena to the Russia. They did not have children. According to Svetlana Skachkova, Elena celebrated her birthday on May 10, her husband's birthday and said that she "had never met a better person. He was a strong and seasoned man who always spoke in a level voice. He was like a stone wall for me. He insisted that I should continue my studies at the department of foreign languages at the Herzen Institute, in spite of the hard times. Thanks to his push I could soon speak three languages and work as a tourist guide in the Hermitage and other museums." And when Nikolai returned from his northern expeditions, they walked the streets of Leningrad holding each other's hands.

They lived in the apartment procured for them by Gorky in the famous corridor-type house for workers of literature and art, 9 Griboyedov Canal. Apartment No.80 later became the famous "Arctic house" where Nikolai received his guests.

Svetlana's grandfather sometimes came to visit Nikolai and Elena. He told Svetlana the following story: "One day, on the way to the Far North, I came to Leningrad with two kids of 4 and 6. Nikolai almost never visited people, considering it an idle pastime, and did not like parties or idle talk. He was a man of action and work. But on that occasion he departed from his principles and all together we went to the circus."

Judging by what Svetlana told us, Nikolai Pinegin was a very charming man full of life and energy. One of his passions was playing the piano. Even during the expedition aboard the Saint Foka he sat down at the piano in leisure hours and played along with some other members of the crew.

He had many friends. One of his closest friends was artist Mikalojus Ciurlionis, who shared Nikolai's passion for music and fine art. Pinegin was also a close friend of Mikhail Zoshchenko and poetess Olga Bergholz. After his acquaintance with Veniamin Kaverin, Pinegin became the prototype of Ivan Tatarinov from Two Captains. "One day Veniamin Kaverin came to visit Nikolai Pinegin and shared with him his plan to write a novel about the North. He asked him to give him his "polar" diaries. Nikolai said that he would give the needed materials, but continued writing about the expedition himself. And they agreed that Kaverin wouldn't write about seamen, but rather write about pilots." That was the background of the novel, known by every citizen of the USSR.

And Nikolai Pinegin lived his last days in obscurity. After his exile his books were never published, museums stopped ordering his paintings, but he continued writing and drawing. He was working on a big novel titled Georgy Sedov. Nikolai Pinegin died in 1940 and was buried on the Literary Causeway of the Volkov Cemetery. He was not rehabilitated until his death. Now the Russian Museum and the Museum of the Arctic and Antarctic keep his paintings Polar Bears, Polar Landscape, Glacier on Franz Joseph land, Broken Ice, Drifting Ice and numerous sketches. In the 1950s his name was given to the cape in the east of Bruce Island and 10 years later – to the lake in the north of Alexandra Land island on the Franz Josef archipelago.

As I was reading the books by Nikolai Pinegin, a brave and resolute man who was crazy about the North and the Arctic, a true friend of Georgy Sedov who devoted his entire life to popularization of the then "unknown land", I thought that he considered the best instances of his life the moments when he was feasting his eyes on the northern sky. "There is a wonderful spectacle in the sky," he wrote. "While here in our earth we see only suffering and depression. Is the night wonderful? Its oppression is felt by everyone living here. Everyday routine is hard indeed. Where is the true identity of the polar night: in its silence, its all-mollifying passion, beauty of the sky strewn with stars or in the spectacles whose luxury are impossible to imagine without seeing it?"

Author: Oksana Prilepina