![]() — Russkiy Mir Foundation — Journal — Articles — Born to Fly

— Russkiy Mir Foundation — Journal — Articles — Born to Fly

Born to Fly

Born to Fly

He had enough woes to fill a dozen of lives, but he wrote writing about happiness. Unlucky and not very fortunate, angry and drinking too much, he is not associated in the minds of Russian readership with dire abominations a la Gorky, but rather with joy, flight, the sea and something so beautiful and glittering, which happens only in good dreams. The prose of Alexander Grin generally resembles a good dream.

And his life depicted in his Autobiographic Story is like a nightmare from which there seems to be no deliverance. Grin's first wife Vera Pavlovna (Kalitskaya in her second marriage) once suggested that there were two creatures living inside him – Grinevski and Grin – who seldom overlapped. "If each of us could be represented in the form of fabric where the white and red threads are intricately but rather uniformly interwoven, Alexander should rather be depicted as two canvases, the red and white ones that very seldom intermix."

Schooner with a bowsprit and two sails

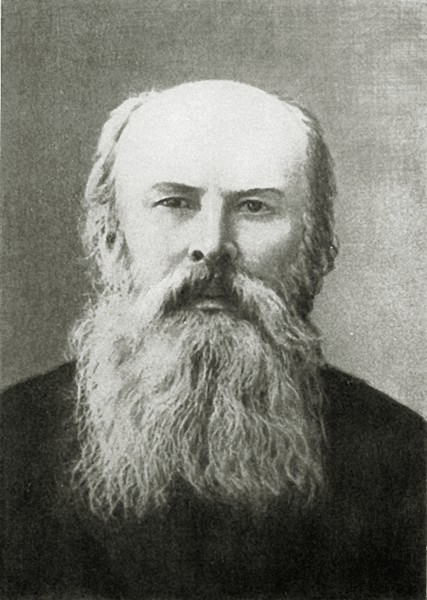

His father Stefan (Stepan in Russian) Grinevski was a Polish nobleman, the son of a wealthy landowner. While still a high school student, he participated in the uprising of 1863 and was exiled to the Tomsk governorate. He later walked by foot to Vyatka, which is a very long distance, and worked as an accountant there. He married Anna Lepkova, a collegiate secretary's daughter. At first the family had no children and they adopted the foundling Natasha, but then children began appearing one after another. Alexander born in 1880 was the eldest; he was followed by Antonina, Ekaterina and Boris. The Grinevski family had almost no money in their pockets and were quite needy. The children were underachievers at school: Antonina was taken from the fourth grade of a gymnasium. The school administration was going to expel Ekaterina from the sixth grade; father took her home and later she passed exams without attending classes. Alexander was a straight A student as far as literature, theology and geography were concerned, but he did not understand anything in sciences and his father always helped him to crack mathematical puzzles. Seeing that his boy was keen on hunting, father bought a rifle for his 10-year-old son and taught him how to shoot. Sasha was a very impatient hunter but could spend whole days hunting.

Restless and inexhaustible in respect to mischief-making and pranks, Grin-blin as he was dubbed by his mates, often stayed after classes without a lunch as punishment for his shenanigans. At home he was scolded and sometimes beaten. Not that father Grinevski did not love his kids: he taught them reading and arithmetic, did lessons with them and put a good word for them, when they were expelled from another educational institution. Nevertheless it was not quite comfortable in the family: children were disobedient, father drank a lot of vodka, insulted his wife and his children occasionally suffered from physical abuse. Their mother, burnt out by her care of the kids and household and her poor health, was angry at everyone. "I experienced physical abuse, standing on my knees. In moments of exasperation my loved ones called me a 'swineherd' or 'golden mouth' for my waywardness and underachievement in many school subjects; they considered me as the most likely candidate for tuft hunting and crawling before more fortunate and prosperous people," wrote Grin in his Autobiographic Story.

Sasha Grinevski was a typical teenager of the late XIX century – one of those who passionately cut burdock with an improvised sabre, imagining themselves great generals, reading James Fenimore Cooper and Gustave Aimard, signing up for Vokrug Sveta (Round the World) magazine, and dreaming of escape to America – exactly like Chekhov's Volodya and Chechevitsyn from The Boys. "Sasha was twice expelled for his shenanigans," wrote Vera Kalitskaya, "but at his father's request he was re-enrolled. He was again expelled from the third grade and this time the soliciting of his parents did not help.”

This time he was expelled for the attempt to emulate Pushkin's squib, where Sasha mocked his teachers: "Kapustin is a skinny pipsqueak, // A dried blade of grass // Which I could crease with ease // But do not want to soil my hands." And so on about each teacher. He was beaten and put to shame at home. Later father transferred his boy to a municipal school which Sasha left in 1896.

His mother died of tuberculosis, when he was 13 or 14. His father soon married again and more children were born into his new family – Nikolai, Barbara, Angelina. In addition, Sasha's step mother had a boy from her first marriage. The relations between the older children and the step mother got off to a wrong start and the father rented rooms for Alexander and Ekaterina that they might live separately.

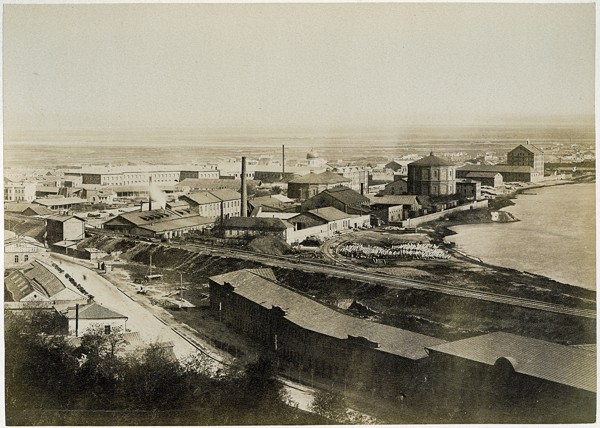

Sasha had long been dreaming about the sea and after he left school, his family decided to send him to Odessa where he could attend seafaring classes. The boy headed for the south with a wicker basket and watercolors, to draw amazing flowers on the banks of the Ganges. When he arrived, it turned out that the enrollment had been closed and his family could not pay his tuition fee anyway. He could join a ship crew as an apprentice, but for a certain fee. Sasha was knocking about the port for a long time in an attempt to find at least some job. Finally, emaciated with hunger, he pleaded to the dockland accountant Khokhlov for help (he mentions that he received a reference letter from a casual traveling companion). The accountant placed him in the boarding house where the beach party lodged; the youth was given clothes and shoes and was soon employed as an apprentice on the "Plato" ship: he wangled the one-month payment from his father.

The ship service he had been dreaming about proved to be rather wearisome; it is echoed in Scarlet Sails: "He was occasionally knocked down by a heavy anchor chain and hit on the deck; sometimes the rope would slip out of his hands, grazing his skin, and the wind would beat him on the face with a wet angle of the sail with an iron ring sewn into it and, to put it shorter, the whole work was a torture requiring a lot of concentration." Grin's nautical service was a torture from the beginning to the end. After a single voyage on board the "Plato" he had to leave, since he did not have money to pay for his further tuition. He ended up in a hospital for the destitute, suffered from malnutrition, lived by begging, and finally was hired by the small vessel Saint Nicholas. But in the end it turned out that he even owed something to the ship owner and he left with a row. He worked at a freight shed, served as a sailor on Cesarevich during its voyage to Constantinople, but did not last long there because he made fun of the captain. The latter sacked him without waiting till the end of the run. A year later he came back to Vyatka with empty pockets, without money or personal belongings, but with a bitter experience. He had sold his watercolors a long time ago and his only treasure – a Chinese cup he bought on his last money for some reason – was stolen.

Several years later he started his army service and the following record remained in his army documents: "Distinguishing signs: a tattoo on the chest depicting a schooner with a bowsprit and foremast carrying two sails." This was perhaps the only tangible trace of his sailor's service. His father hoped that the grown-up son would help the family rather than keep asking for money. He helped enrolling Sasha at the railway courses, but Grin grew bored there and dropped out. He started copying roles for actors, but a year later he had the blues again and set out for the south, craving for adventures – this time to Baku. That year was even worse than the one in Odessa: "hunger and gloom." Sasha even tried to work at dockland's oil and fishing companies, doing any work that was available, and contracted malaria. On one occasion he nearly died of thirst, having incorrectly chosen his path under the scorching sun. He stayed at hobo jungles overnight and asked for alms. Hardly any of the well-known Russian writers had a more dreadful youth – maybe only Gorky and Sologub. No wonder that all three later became romanticists – some of them revolutionary, and some decadent. Most likely, because it is absolutely impossible to endure such living, unless one takes pride in his human origin and there are the Liss, Zurbagan and Mair star.

He came penniless to Vyatka again and returned to role copying and then found a stable job and earnings, but again grew bored and left. At first he wanted to live by hunting like Cooper's famous character. He worked as a bath attendant and sailor on a river barge, and drank hard. He was a copyist under an attorney at law and then decided to tackle gold mining and left for the Urals but did not hold out long enough. He came back, lied to his father that he robbed the gold miners' office with a gang of robbers, but reveled away all of this money. His father was deep in thought: "I wonder what will come of you."

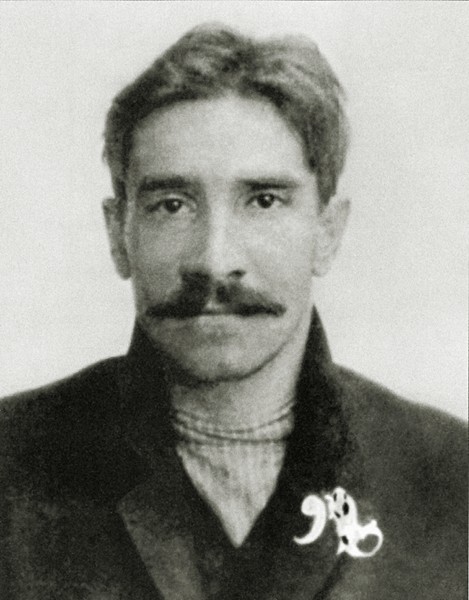

Love and revolution

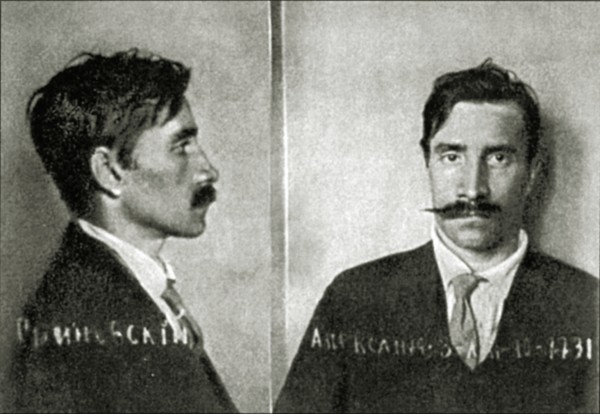

In 1901 Grinevski turned 21 – the time for army conscription. He was granted a half-year deferral given the conscript's frail stature, but in 1902 he was called up. He learned to hate the army service from the very first days. Out of the nine months of the army service he spent three months in disciplinary confinement. While in the army he met revolutionary Studentsov and decided to join the revolutionary ranks. His socialist revolutionary friends helped him escape from the army and now his life was governed by the party that sent him from one place to another. He soon realized that the very idea of terror was disgusting to him, that this was not his way. The party thought he would make a good agitator, for he spoke very passionately and convincingly. He was sent to sailors and soldiers who treated him as one of his own. He later recalled: "It turned out that after I spoke at one rally and left, one soldier threw his forage cap down to the ground and exclaimed: ‘Ah, even if my parents and wife and my children are ruined, I am ready to give up my life for this cause!’ The party work again brought him to the south – Ekaterinoslav, Kiev, Odessa, Sebastopol – where he met his first real love – Ekaterina Bibergal. She is mentioned in his Autobiographical Story as "Kiska". Her several photos have remained: the ironic squint reveals her unordinary and smart personality. Grinevski proposed to her and she promised to marry him, but then public justice meddled in their love story. The soldiers agitated by Grinevski betrayed him to the police. He refused to bear any witness, did not name himself and did not collaborate with the investigation department and spent two years behind bars, trying to find any chance to break free. Kiska left for Switzerland and came back after the amnesty of 1905. But instead of reunification a drama took place: he was tired of being hungry and cold, of hiding and fearing, of waiting for the next detainment and possible perdition. He wanted to live and love while she wanted to sacrifice herself for the sake of the revolution. In his story The Oranges (1907) a convict tries to read Das Kapital in jail: "Dry, mathematically clear lines were flashing before his eyes, falling into some strange void, leaving no traces like snowflakes. And he felt cold and boring from those relentless lines, poisonous like the Devil's laughter, indefatigable and calm like the swinging of pendulum." Meanwhile spring was looking into the cell's window with its "countless tender eyes," and the blue river was glimmering with golden spangles.

This is what Vera Kalitskaya had to say about Bibergal: "She saw a talented agitator in Grin who at the moment of his utmost passion could lead those who were listening to him. It is during such moments that Bibergal developed affection for him." He decided to break off with the revolutionary cause and she said that once he had abandoned that cause, he no longer existed in her life. He tried to keep her, but she did not want to be with him. Then he took out his gun and pointed at her. She wouldn't budge. Grin later wrote: "She was defiant and extremely courageous. I knew that I would never be able to kill her, but I could not reel either and fired." In the same way Tart shoots at Blemer who was pursuing him in Island Renault – one of his first "non-Russian" romantic stories – "the air bubbling in Blemer's broken lung was so audible and tangible, with sticky blood oozing through his fingers. Tart shoots so recklessly and is so perplexed later that you never doubt that the hand which wrote Island Renault would never shake, triggering the hook just several inches from someone's chest..."

A bullet hit Kiska's chest and got stuck in her side. The wounded lady even came out to the room of the apartment owners and asked them to plead with Grinevski to leave. He left, and Kiska was operated on by a famous professor. She recovered but never let him speak one-on-one with her and gave him no more chances. He was arrested in 1906 and they never saw each other again. She spent several years in a forced-labor camp; there is a well-known photograph of hers among other women convicts, members of the Socialist Revolutionary Party (SRP), including the famous Maria Spiridonova. Grin sent her his book with a story titled A Small Committee. This is talking about a city revolutionary committee: "The committee wears a skirt; she is 19, a dark blue-eyed blonde. It is a very small committee." Kiska's post-revolutionary fate is also quite typical of a socialist revolutionary: Stalin's camps and exile.

From revolution to writing

Revolutionary Grinevski was placed in St. Petersburg's prison Kresty and the Red Cross that helped convicts took care of his dates with a fictitious bride, as he had no loved ones in the city who would bring him parcels. A teacher from the evening school for workers Vera Abramova was appointed as his bride. During the date Grinevski gave a farewell kiss to his "bride" and she was rather embarrassed. Grinevski soon left for exile and was to spend several years in Tobolsk governorate, but escaped the next day after his arrival and returned to St. Petersburg with another man's passport (V.Vikhrov writes that his father got for him the passport of the deceased "honorable citizen Malginov") and immediately made his way to his bride who soon became his civil wife; for he could not get officially married in church with a counterfeit passport on hand. It is around this time that Alexander’s first attempts at writing begin. The stories were written at the party's commission as propaganda materials: The Merits of Private Panteleyev – a story that was later confiscated and burnt – and An Elephant and a Pug. The editor and publisher of The Merits of Private Panteleyev was incarcerated, but they did not betray the author – the story was signed "A.S.G.". Incidentally, the private's merit was that he shot down a peasant during a revolt; the text was meant for recruiting among the soldiers. Another story The Incident on the same subject was the first printed text signed by "Grin"; later it was conjectured that the author assumed that pen-name for the sake of foreign zest. Yet there was no foreign colors in Grin's first stories, but the escaped exile living by another man's passport could not disclose his real name; after all, Grin was just his childhood's nickname.

Grin's first stories were in the style of "critical realism" as opposed to his later prose: "At night, when everything calmed down and stinking foot wraps and shoes were rotting in the stale sultry air, when obscure and morbid sounds could be heard groaning behind the smoked logged walls, produced by piled bodies broken with fatigue and slumber, Yevstigney jumped up and scolded, mumbling something very fast, then bent down his head, scrubbed his hair and fell again onto the hard and smooth boards." Such text could be written by anybody; a lot of these could be found in Russkoe Bogatstvo (Russian Wealth) or Mir Bozhiy (God's World) magazines, or in the Znanie (Knowledge) collected stories. Several years had elapsed before he found his way in prose. His first collection of stories Shapka-Nevidimka (Cap of Darkness) tells about underground revolutionaries. Grin realized that he wouldn't make a proper revolutionary: he did not approve of terrorism, got tired of homeless living, waiting for another arrest, endless wanderings. Says his wife: “It is because of this nervous fatigue that Grin forewent his party work, having openly declared: ‘I don't want to work any longer, I'm tired and do not want to take risks’.” And now as the revolution ended in 1907 with universal frustration, weariness and languish, Grin the romanticist comes to replace Grin the underground revolutionary.

A terrible thing happened to the word "romanticist" in Russian: it got hopelessly vulgarized and debased. A romanticist of the 19th century is a grim loner telling hair-raising stories about strong-spirited people overcoming fearful circumstances. In the vapors of absinthe he discerns vague warnings regarding the future, recognizes wild and wonderful tunes and sees beautiful far-off lands where nature is not degraded by civilization while the morals are primordial and severe. In the early 20th century a romanticist is a person inspired by a great idea, confident in its mighty power and his own ability to reform the world and make it suitable to live in. But already by the late 20th century a romanticist was no longer associated with the somber might of romanticism but rather with snotty and weak-spirited romantics. Grin had particular bad luck here, as his fiction was swapped for the tinkling of a guitar, songs about a brigantine and girls' dreams about romantic dates and yacht strolls that would be sickening for any true romanticist.

The first "non-native" work by Grin is Island Renault: sailor Tart decided to defect from his ship and stay behind on a beautiful island. Here we find all Grin's major motifs unraveling: disappointment in the human society, the search of something genuine and, most important, the moment of happiness quite typical for Grin, when the dreary reality suddenly breaks loose, with a miracle emerging in its core: "For about a minute, thrilled with delight, Tart did not dare raise his eye-lids, that the unexpected splendor around him may not seem a casual whim of the mind. Yet hot powerful light penetrated through his eye-lashes as a red fog, and impatient joy opened his eyes..." This was followed by a pure song, a symphony of happiness, composed from the splashes of waterfalls, rainbow, shaking of golden drops, and not a single false note was sounded.

Grin is a wry personality, a morose and heavy drinker, and a real bastard when on the booze – he knew his urge for morbid fantasies and unsavory visions (he wrote several absolutely morbid, decadent and eerie stories about it). He consciously suppressed this urge in him; thus one of his characters, a painter, hides and eliminates his infernal creations instead of showing them to the world: "... a river dammed with green corpses; the intertwining of hairy hands clenching blood-stained knives; a pub crammed with drunken fish and lobsters; a garden with gallows taking mighty roots and growing tall with the hung tossing on them; their long tongues were hanging down to the ground and these tongues were used by laughing kids for swinging..."

By modern-day standards, all these flowers of evil are quite an innocent mainstream; Grin could have easily become the master of madness, blood and horror – he had ample natural gifts for this mission – not in vain was he constantly compared with Edgar Poe. And he paid a generous tribute to this aspect of his talent in The Heritage of Pick-Mick series written in times of WWI.

Nevertheless Grin did not become a Russian Poe. The latter is a master of darkness, well and pendulum, whereas Grin is a master of the wind, running on the waves, sun spots and flights in waking. In 1916 he came up with the following formula: creativity is the embodiment of every manner of freedom.

He can be angry, tough and even cruel, but the dazzling shine of happiness and masterly musical soaring are absolutely unfeigned in his prose, and this is top class writing, one should admit: it's easier to frighten readers than to exalt them. Making them weep, holding their breath in horror and strain is easier than making them gasp in delight, burst into unrestrained and happy laughing in the fullness of one's soul. Few are adequate to this task, but in that generation many writers could do that. Blok who was the same age as Grin definitely could: "the reed pipe's singing on the bridge, and apple-trees are in bloom..." The critic Gornfeld, who authored the first large and positive review about Grin, said: "He wants to speak only about important and fateful things: not in our everyday life, but in the human soul."

The review was published in the magazine Russkoe Bogatstvo (Russian Wealth) which incidentally selected Grin's quite traditional story Ksenia Turpanova from the life of exiles: a wife left the island to buy a gift for her husband who meanwhile brought another woman to their bedroom...

Over the course of several years Grin changed literary styles, writing traditionally, and then in a new manner, refining his craftsmanship and inventing his own world: putting new lands on the map, settling new inhabitants there, transforming reality.

In 1907-08 he joined the ranks of St. Petersburg writers, started visiting editorial offices, meeting men of letters and, like many of them, whiling away hours in restaurants and pubs. He had drunk a lot before that, but now he sometimes was several days away. His royalties and fees could not pay for his lifestyle, to be sure. In fact he lived on his wife's money.

He was again arrested in 1910, but now he could wed officially; Vera Pavlovna did a lot to make this happen; the prisoner was brought to church, with Grin's sisters and police agents present at the wedding. Almost immediately the newlyweds set out for exile in the Archangelsk governorate where they lived two years. This time was hardly idyllic: everything ended in a divorce at Grin's initiative. His wife did not object: it was ever more difficult for her to bear up with Grin's rudeness and debauchery. Nevertheless they remained good friends to the end of his life and Vera Pavlovna who could discern Grin's tender, flying soul in the evil and disharmonious Grinevski calmly and benevolently helped him and his second wife.

Nowhere to get published

Before the February revolution he resided in Finland and upon learning the news he went to the city by foot because trains did not run at the time. Neither letters nor records for this year have remained. "Two men who saw him after February said they often met him at spontaneous mass rallies. He was taking a closer look at the situation and bent his ear to what people were talking about," writes his biographer Vladimir Sandler.

His life after the October revolution was similar to everyone else's lives: he was hungry and impoverished. Books were not published, there was no way to earn a living. Nikolai Verzhbitsky says in his recollections that Grin lived in a small country house in Barvikha: he had no personal affects, save for a small suitcase with a change of clothing, and had no bread cards either. He picked mushrooms in the forest, roasting them on the fire and eating; sometimes he stole potatoes from the field and ate them raw, because the house owner would not allow him to cook at home. In the fall he fell in love and moved to the place of a little-known woman named Dolidze; he lived three months with her, but then got insulted at the fact that jam was hidden from him and the cupboard was locked: "I am not a toady and it is not my fault that I have nowhere to publish my works. I'd then pay back everything. I told everybody to get lost and left," he wrote to Vera Pavlovna.

In 1919 he was conscripted by the Red Army. He served in the rear – with the telephone team at Okhta. He had always been disgusted at the military service and sang the blues; finally he moved to the medical staff in an ambulance, just out of boredom, but the doctor found him too frail and the medical commission gave him a leave. He returned to Petrograd but fell very ill – it turned out that he contracted typhus. Gorky found a place for him at hospital and after a course of treatment sent him utterly emaciated to the House of Arts on the Moika Quay, where writers and artists found a shelter from cold and famine and tried to uphold cultural life, publishing a magazine, delivering lectures and staging recitals.

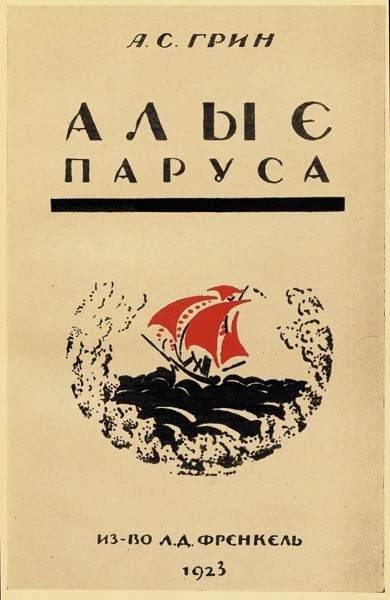

In December of 1920 Grin read his Scarlet Sails in the House of Arts (benignly received by the audience and later by readership and, with a rare exception, by critics). In the House of Arts he came out with his weird Ratcatcher inspired by his joint visit with Victor Shklovsky and painter Milashevsky to the abandoned bank premises to look for books they wanted to use as kindling.

On March 8, 1921, Grin married Nina Mironova and this marriage lasted to the end of his days. As it happens with happy lovers, everything went on fine and yet his financial standing did not improve: because of havoc, ruin and the publishing crisis he could not publish his works anywhere. Many writers got off thanks to collaboration with Nakanune (On the Eve) newspaper published in Berlin. But on his big royalty from Nakanune Grin fed 10 hungry writers, as was attested by E. Mindlin.

Publishing houses started emerging in 1923 with the beginning of NEP (new economic policy) and Grin's financial affairs improved: publishers willingly published his works, but delayed his royalties and he had to fight his way all the time... In 1924 Grin moved to the Crimea with his wife and mother-in-law: there was no urban fuss there, no housing consolidation or housing management offices. He had more opportunities for concentration and work there and living was cheaper. He had to burden his friends with requests to wrench his royalties from the publisher, though. On the other hand, Grin had a lot of inspiration to write. He lives quietly, rides on a boat, thinks and creates one after another his best works ever: Jessie and Morgiana, The Shining World, The Golden Chain, She Who Runs on the Waves. The mid-1920s was the time, when the reader was longing for extraordinary adventures and it was still possible to have his new manuscripts published. Meanwhile it was getting tougher with each passing year: now it was necessary to fulfill the social order. The Golden Chain was already criticized for the lack of any links to modernity. Verzhbitsky remembered Grin arguing against writing about factories, having pleaded his "fear and hatred of machines" and Yuri Dombrovsky recalled how Grin calmly responded to the proposal to write something antireligious that he believed in God. She Who Runs on the Waves was stalled at the "Zemlya & Fabrika" (Land & Factory) publishing house and yet eventually came out. This was not to be the case with his collected works in 15 volumes that were launched by the "Mysl" (Thought) publishing house: the publication process was halted after volume 8 and Grin entered into litigation with the publisher.

The years 1929 and 1930 were the darkest period for Russian fiction, the "great turning point", when writers were reviled, forced to deny their principles, to pledge allegiance to the Soviet power, and to swear that they would write only about contemporaneity. Grin was physically hungry during this period: there was no money and famine began in the Crimea in 1930. Grin was seriously ill; at first his doctors suspected tuberculosis, but then shortly before his death they diagnosed a stomach cancer. Only his application to the Writers' Union helped him publish his Autobiographical Story and thus raise some money; nevertheless this money did not save him: emaciated and exhausted, he never rose from his bed again. There was indeed no place for Grin in the upcoming reality and he passed away exactly at the time, when he was no longer in demand as a writer.

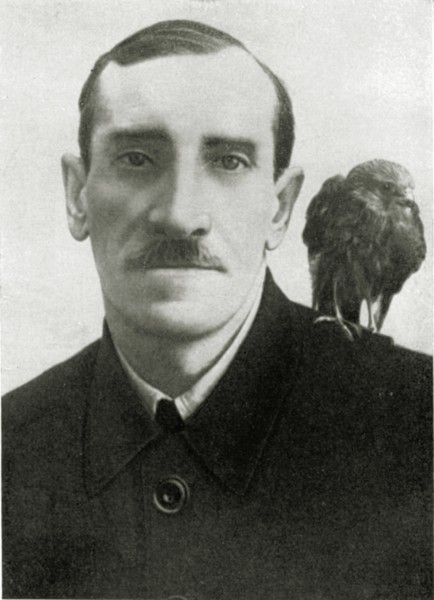

He had his favorite pet falcon Guhl who died in 1930. The falcon had a broken wing and could not fly; it seemed to Grin that he died of boredom. Grin had dreamt of flying during his lifetime in the same way as the main character flies in The Shining World – in an unrestrained and unsupported manner as though in a dream, without any mechanisms or props. This is what he wrote to Vera Pavlovna after Guhl's death: "I shared my fantasy in the magazine about Guhl starting to fly because I wanted it very intensely. And I think God had mercy on him. He was not happy anyway." He says in his Story of One Hawk: "I let him fly up from my yard in the morning and Guhl smoothly flapping his wings soon was hidden from view, bound for the mountains."

Flight and joy, the trembling of golden spangles on the river, the blue cascades of the waterfall Telluri (the very name is the epitome of happiness!), the scarlet gleaming of sails in the morning mist at the river estuary, impatient anticipation of the wonder towards which the soul turns around like sails, like wings but cannot take off.

Author: Irina Lukyanova