![]() — Russkiy Mir Foundation — Journal — Articles — In Vavilov’s Footsteps

— Russkiy Mir Foundation — Journal — Articles — In Vavilov’s Footsteps

In Vavilov’s Footsteps

In Vavilov’s Footsteps

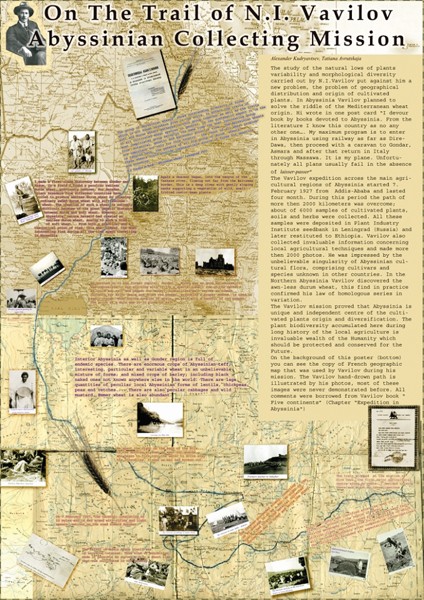

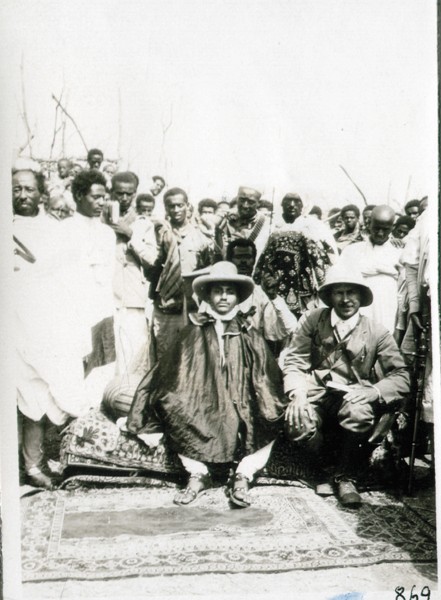

In 1927 outstanding Russian geneticist, plant breeder and geographer Nikolai Vavilov set out for a distant expedition to Abyssinia where he collected unique crop seed samples. In November-December of 2012, 85 years later, the researchers from leading Russian institutes specializing in genetics and crop husbandry traveled in Vavilov’s footsteps. Project Director, Doctor of Biology, Deputy Director for Research of Vavilov General Genetics Institute Alexander Kudryavtsev told about this expedition in his interview for the Rusksiy Mir.ru.

“The idea of such an expedition emerged 7 years ago,” says Alexander. “In the beginning of the 2000s I worked in Ethiopia for an Italian territorial development project and was studying the selection varieties of wheat. And when I returned to Russia I argued at the Vavilov Readings that the genetic diversity of Ethiopian wheat was rapidly vanishing. Vavilov believed Ethiopia to be the original land for the cereals and brought the richest collection. Director of Ecology and Evolution Institute, Academician Dmitry Pavlov proposed to repeat Vavilov’s itinerary, picking wheat specimens at the points where findings were made in 1927 and then, using contemporary lab tests and genetic analysis, to compare the new material with the samples of 1927. It will thus become clear what is going on with the wheat diversity.”

– And it took you seven years to organize that expedition?

You know, for anything to be done in Ethiopia, you must collaborate with local academics. And Director of Ethiopian Biodiversity and Conservation Institute – a key institution in our research – was geared towards working with Germans and did not want to cooperate with Russia. In 2011 the Institute was helmed by a new director who supported our idea, though this was possible only thanks to the active involvement of Andrei Darkov who constantly works in Addis Ababa and spearheads on the Russian part a joint Russian-Ethiopian expedition there. This very organization actually sponsored our travel.

– How did you reconstruct Vavilov’s itinerary and map specific sites of various wheat species?

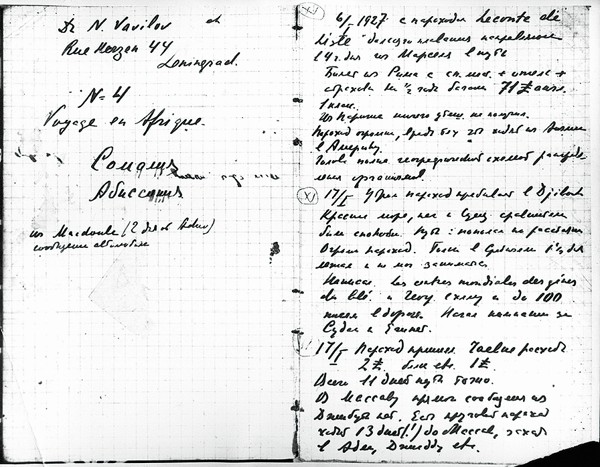

A copy of the map of the 1927 expedition is extant. Moreover, Vavilov described in The Five Continents his Abyssinian trip; reports on the expedition’s results are also available and, what is most important, Vavilov’s detailed diary has been preserved. One of our expedition’s participants, employee of the National Vavilov Plant Breeding Institute, put together all of the sources.

It should be noted that the 1927 Diary is the most interesting book that does not only narrate on scientific discoveries, but also describes the life in the Ethiopia of those years and the Russian researcher’s adventures in Africa. Regrettably, we have only part of that diary. When Vavilov was rehabilitated in 1955, public-political interest was kindled to write about this great scientist as a victim of Stalin’s regime. Journalists started feverishly raking in the archives and one of them found the Abyssinian Diary. Afterwards that journalist left for the US and took these archives with him. Vavilov’s Diary is still kept by that journalist’s widow. Hopefully, we’ll be able to redeem it for Russia. But now the Diary also has certain auction value and can be sold. Nevertheless the custodian of the Memorial Vavilov Office Museum at our Institute, Tatiana Avrutskaya, somehow found a photographic copy of the first part of the Diary that had been made before it was grabbed by the journalist. Reading the extant manuscripts proved a challenging undertaking. Vavilov had an illegible handwriting and the text was saturated with acronyms and terms. We could identify some of the words only on the spot. We plan to publish the decoded part of the Diary, illustrating it with photographs from Vavilov’s archive. The materials about our expedition will also be included.

– How does the research caravan of the XXI century look?

This was certainly the caravan of jeeps. We drove more than 5000 km. Modern-day roads generally coincide with Vavilov’s itinerary, but some places are impassable – even now there is a donkey’s path there. We had to make short radial detours to the points where the specimens were discovered in 1927. Five experts from the research institutes of Moscow, St. Petersburg and Novosibirsk as well as an Ethiopian specialist named Mulegeta from Biodiversity Institute participated in the expedition. We did not lay out any field camps. Ethiopia now has rather dense population along the main roads so we stayed at hotels, although some of them could hardly be called by this name. Sometimes it would have been better to spend the night right in the field.

At some lengths we were joined by the employees of the Russian Center of Culture in Addis Ababa, who delivered lectures on our expedition at three national universities.

– The travel of the great Russian scientist was probably a revelation for the attendees?

Not in the least: people of Ethiopia know about Vavilov, not only academics – above all, because Vavilov extolled Ethiopia as the origin of cultivated crops and plants, and Ethiopian teachers are delighted to tell schoolchildren about it.

– For you Ethiopia is no longer exotics, to be sure, and what impression did this land make on those members of your expedition who were there for the first time?

Ethiopia grows on you. We were also accompanied by a filming crew preparing a documentary about Vavilov. They were eager to make some footage and said: we’ll beautify the landscape by means of picture scenes and drawn crocs. But they were amazed to see the original life of Ethiopia. No staging was needed. They shot 15 hours of footage and said they would need a year to sort it out, edit and make a full-size documentary about the expedition. Already now the producers affirm that the material is worthy of being shown on the leading federal TV channels.

Ethiopians have largely preserved their original culture; many wear national garments, reap corn with their sickles, use oxen and a sort of wooden spear to plough the tillage. At 5 a.m. people in white garments gather at the church from surrounding neighborhoods and villages to sing Christian hymns and at 10 a.m. ‘white clouds’ of church-goers move back home. I was absolutely fascinated with this tradition. Ethiopians are a very special race, beautiful, curious and outgoing people and yet not very obtrusive by the African yardstick. To be sure, wherever we appeared, large crowds immediately surrounded us, but people would never grab you by the hand to pull somewhere – never.

And the landscapes are just stunning! Imagine us driving over the upland, more reminiscent of our Kuban steppes and fields and then suddenly the high-altitude plat plunges deep into a kilometer-deep and 20-km-wide vale strewn with huts and fields and the Nile flowing down below, as though you look at it from space – pure air, the temperature is about 25 degrees Celsius and you feel very comfortable.

– What was the attitude of the rural population to your studies? Did they help? And how did you generally communicate with them?

It was Mulegeta who was responsible for all contacts and it was rather amusing to watch. He would call up the first passer-by in a new village. The latter comes up and bows, as if he were speaking to the King of Ethiopia. Mulegeta says something in a commanding tone and the lad runs back and brings farmers with him. We seat them in our jeeps and drive to their crop fields. Villagers walk with us half a day, tell us a lot of things, show the crops and help us pick them. In the end Mulegeta says they must be paid. We give them miserable money by our standards, but people are happy to get 100 rubles each for their work.

Meanwhile we had to look out for plantations of the traditional purple wheat, since large fields along the road were sown with modern species – partly, for political reasons. Many farmers said they had a quota from the Ministry of Agriculture that ordered them to sow only contemporary varieties. The hidden sense of those quotas is in building up the market of mineral fertilizers which are indispensable in wheat growth nowadays, while the old varieties do not require any fertilizers, even though their crop yield is 1.5 times lower.

Only farmers know where traditional wheat grows. They helped us find small fields of purple wheat. Traditional wheat is most often grown for religious purposes. Only the purple wheat is used to bake bread for the Eucharist. We did not find these varieties in the area of Axum at all. When we turned to the regional division of the Ministry of Agriculture, we were sent to the farmers’ convention that was under way right at that time. We go there and the chairman of the farmers’ association sends us to a priest. The reverend brings us to an out-of-the-way village and introduces to a certain one-legged farmer who shows us his tiny 5x5 m field, sown with Ethiopian wheat.

– Are Ethiopian farmers any different form people of other trades?

In our eyes they were not different, but Mulegeta confidently spotted the farmers. Every time we approached a grain vendor at a market, Mulegeta immediately said this was not the right man to buy from because he was a reseller – let’s go to that farmer and he will tell you exactly what kind of wheat it is and where he grows it.

– Vavilov writes about numerous adventures accompanying him in his journey. Is the same romanticism still part of the traveling experience?

Driving is in itself an adventure in Ethiopia. I got the Ethiopian driving license and stayed at the steering wheel throughout the expedition. People walk along the roads there – sometimes at the roadside, but they may cross it all of a sudden; any route is also strewn with cattle. You won’t want to drive in the nighttime, since you may not notice black people dressed in dirty clothes.

Crossing the Simeon Mountains to Axum is a special story. The upland at the altitude of 2800 meters suddenly plunges downward almost vertically. The serpentine road winds down by more than 2 km to the altitude of 500 m above the sea level. There is no asphalt, just a narrow earth road winding up a steep slope with waterfalls. At one place the road is expanded with a bulldozer: cobblestones are flying, workers drowsy in the sun occasionally warn to be careful, but sometimes they don’t… Then they start rolling back huge boulders, to clear the roadway. Finally we get down to the lowland where the temperature is 110°F, unlike 70°F on the upland. No sooner do we catch our breath, than the road climbs 1.5 km upward again, followed by another descent. At a stretch of 100 km the road thus dives and soars seven times, and it took us 8 hours to drive this distance. Even Mulegeta turned pale from such altitude drops and fell fast asleep the moment he got to the bed.

Without any acclimation to altitude, I kept struggling with drowsiness at the steering wheel. The filming team would always come to my aid, as they stopped our caravan every time they saw wheat being thrashed by donkeys. And while they were shooting their footage I was able to have a nap.

On one occasion we drive from Harar to Jijiga on the Somali border. Even imperturbable Mulegeta feels nervous and says we should get out of here until it gets dark. We keep driving and see groups of khat-chewing Somalians with empty eyes standing at the roadside with Kalashnikov guns on their shoulders. Mulegeta gets out and tries to ask them something. I say it’s time to turn around and he says we should not be afraid, for they have no ammunition rounds. They shot away their stock long ago and the supply chain does not work, praise God. Their men wear sub-machine guns just for the sake of solidity.

– In 1927 our academician had to formalize an agreement with caravanners. Is bureaucracy still strong in Ethiopia?

You cannot work in this country without a paper from the Ethiopian authorities. The police asked the filming crew several times to produce a permit from the Ministry of Culture. We had a cooperation agreement with Biodiversity Institute and certainly Mulegeta who spoke very confidently with everyone. At first we even decided that he was a secret Ethiopian agent in the rank of colonel. For instance, we had a long journey from Gonder to Axum. There are no gas stations between the cities and we had to find fuel in Gonder. Diesel was missing in that provincial capital. Mulegeta even intended to claim the strategic reserves for us at the Ministry, but at the last gas station he had a serious discussion with the locals. They bowed to him and fueled our jeeps at a hidden dispenser. Well, how could a common technician from the Biodiversity Institute do that? By the end of our travel we made friends with him. He wasn’t a secret agent, to be sure, but simply a very charismatic individual who had a profound knowledge of local life and psyche. Mulegeta has worked at the Institute during his lifetime and now he has a personal tragedy as people are forced to retire at the age of 60 at the Ethiopian state sector. Pensions are miserable, the Institute is interested in his services, but they cannot thwart the rules.

– They tried to “make it hot” for Vavilov on the road in order to claim a “backshish”…

These tricks are still used today. We were warned straight off that they might push a cow under our wheels and so we were driving very carefully. Only on one occasion a lad standing at the roadside suddenly yelled that our car rode on his foot. But this was too obvious a deception. If we ran over his foot, he’d be screaming in a different way.

– “Abyssinia is undoubtedly home to the coffee tree while Harar is the center of its cultivation and trade,” says Nikolai Vavilov. Has anything changed since then?

The district of Harar and Dire Dawa is almost fully sown up with khat now, whereas coffee plantations have been uprooted. Khat is a very profitable business. Regular khat flights head for Europe and America, with immigrants being its key consumers. In Ethiopia khat chewing is forbidden for Christians – the Church may shrive transgressors – so Moslems are its main consumers.

– In 1927 money was not accepted on the Gonder market, with barter trade prevailing; sometimes people paid with lumps of salt. Our academic was sometimes taken as a white wizard who might put a hex on the merchandise and so they hid grain from him…

They did not hide it from us because we were in the company of Mulegeta who explained everything and reassured those who feared witchcraft. Money is now accepted anywhere – at least at the roadside – though lumps of salt are still on sale in Gonder.

– Vavilov was writing that Abyssinia was the land without songs and music. What’s your impression?

Music, songs and dances are mainly ritual and they are broadcast at churches through amplifiers for the entire district to listen. Back in the days of Vavilov there were no mikes and so he did not hear any music. You can very rarely hear secular songs indeed. Perhaps only on one occasion did we see an establishment with national music and dancing in the city of Bahr-Dar. Women were performing Ethiopian dances and pulling men from the tables for joint cross-cuts. After a dance the invitee traditionally licks a 10-birr note and sticks it to a woman’s forehead. Everybody feels very happy. These places are not meant for tourists – they are overcrowded with Ethiopians.

– And did you see any cemeteries transformed into “botanic gardens”?

We wanted to find such graveyards, but you’ll never come across them at the roadside. Vavilov was in a different situation – he was traveling in a caravan and was not in a hurry. The guides themselves tried to bring the caravan to a cemetery that everybody would be fed there. According to Vavilov, cold-meat parties were made almost non-stop at churchyards – not because people died every day, but simply because one of Ethiopian customs is to arrange a funeral repast every 40 days.

– In Abyssinia Vavilov found “a curious bundle of Russian frats”. Did you ever come across compatriots?

We did not. Nevertheless Ethiopia magnetizes the Russian man and you feel the urge to return there. Probably this has to do with the common Orthodox roots and the Orthodox world view which formed similar cultures in different ethnic environments. Perhaps Ethiopians are closer to us in spirit than even Europeans. At St. Gabriel Church in Kulubi the arch-priest received us as his dear people and told us: you are our brethren, feel at home here. The churches are full of icons painted by Greeks and you may come across some icons from Russia.

We did not meet Russian people on our way, but often came across Russian-speaking Ethiopians. Hearing the Russian speech, people came up, greeted us and recalled with ecstasy how they had studied in Russia. On the other hand, uneducated people often do not have the slightest idea about Russia.

– Vavilov was asked about Lenin and the sociopolitical system in the USSR. What aspects of Russian life interest modern-day Ethiopians?

Now they ask about Putin, but on the whole Russia is not so close to them now as it was before. The older generation who remembers the era of closer ties between our nations recalls how great it was in Ethiopia under Russians. There were machines, construction sites, studying in Russia. Russian specialists worked everywhere as medical doctors, teachers, engineers. Younger folks know little about it. Nevertheless Ethiopians willingly get in touch with Russia, rather than with people from the West. When we organized our expedition, my Italian colleagues suggested that this project should be international and that European researchers could be invited. Ethiopians refused, saying they would interact with Russians and would have no dealings with Italians. Biological piracy embittered them against Europeans. In the late 1990s it became possible to patent biological substances. Thus the Dutch patented the Ethiopian endemic and national cereal plant teff. Now the Dutch hold a copyright to any teff-containing products on the territory of Europe.

Many wonder about the Russian Orthodoxy. In one of the monasteries on an isle of Lake Tan we came across a monk who spoke fluent English. He asked us about the monastic life in Russia, shared the experience of monastic life in Ethiopia and said he would like to visit the Trinity Sergius Laura in Russia. I had an impression that the monastic way of life is very similar in Russia and Ethiopia. It’s difficult to render it formally, for it’s something about critical reevaluation of everyday living, human attitudes and the way our brain functions. I’ve been to Russian monasteries, resided in Solovki and have some experience in this area. I just have a feeling that both here and there people reason in a similar way.

– What’s the significance of the Abyssinian expedition for Russia?

Vavilov brought 400 samples of wheat from Abyssinia and now we have about 150 at our Crop Breeding Institute (CBI). The task of Vavilov and our expedition is conserving and studying wheat varieties. At first the promising forms are identified and then the plant breeder interbreeds them, creating a new variety that goes into production. This work allowed the creation of such species in the XX century that fed the whole mankind. Thus in Russia from XVI century to the early XX century the average crop yield had been 300 kg per hectare – 150 kg were sown and 300 kg were harvested. Interbreeding enabled an increase of the average crop yield in the country to 2000 kg per hectare and in Kuban the average crop yield is 5000 kg/ha. In other words, the crop yield increased 20 times. Bezostaya-1 – the variety created with the help of African material – marked a major breakthrough. Little work has for now been done with Ethiopian wheat species. The key problem is that these are all short-day varieties. While we have long days in summer, they have an almost unchanged duration of day and night throughout the year – 12 hours. Yet there is a multitude of unusual features and genes in the purple wheat that could be very useful. For instance, Ethiopian sorts have a unique resistance to diseases and never ail. In addition, they have a big ear and large-size grain. We should build on these characteristics. And in this country crop husbandry and seed farming were ruined and still abide in a deplorable state – they have just started recovering.

On the whole we have the following situation: everywhere in the world we see a swift process of waning agricultural diversity. The main trend is towards uniform crops. This already takes a toll on the consumer, since there is a limited range of tastes. Yet under the global climate change this homogeneity will not be able to exist under different weather conditions. This is what happened in Ethiopia, by the way. The horrible famine of the 1980s that took away more than 400,000 lives was not only caused by the drought, but also by the fact that pandemics destroyed huge plantations of new wheat species.

The imported European varieties became extinct and yielded no crop for two years in a row. And even now the plantations of selection varieties are sick and the fields need spraying. This incurs extra costs and the mix of resistance genes is curbed. Whereas there is a great multitude of pathogenic agents in Ethiopia and nobody knows at what point the next fungus race may spring up. This may also happen on the world scale and so we must conserve the strategic biodiversity reserve, for only then will it be possible to create new varieties accommodated for the new weather conditions.

– What’s the share of Vavilov’s samples in the Seed Stock of Cultivated Plants at CBI that is said to be estimated at $1 trillion?

This is by no means its market value, but the estimation of UNESCO that wanted to show in this way how this stock, the world’s wealthiest, benefits the humanity. The number of samples totals to several hundred thousand. Vavilov began creating this stock and brought about 30,000 specimens. But much of this wealth perished at the time of Stalin’s purges. For instance, the Afghan collection of Vavilov was simply thrown away to rot in the rain. In the wartime there was nobody to keep an eye over the repositories: some species were eaten by rats and the ceiling leaks caused the decay of others. And yet the stock was not eaten during the blockade famine, since it was looked upon as having a high value.

– Is it possible to sum up the results of your expedition already now?

Investigation of the samples is scheduled for 2013-2014. The material was placed at an Ethiopian genetic bank. We brought back just a small portion of the material to study it using molecular-biological methods. Now CBI is holding negotiations – the material may be handed over for further investigation in the Russian field. These were the initial conditions: it was stated that the samples could not be just deposited in the genetic bank or used for selection, etc. Ethiopians regard biodiversity as their national asset and strictly control it. Unlike us, they realize that biological resources are probably a more valuable asset than even oil and gas, because this is what will feed millions in the future.

In the course of our expedition we picked 60 wheat samples and even this proved an awesome challenge. However we’ll yet have to clear up how diverse they are. While Vavilov brought more than 100 varieties from Ethiopia, we found about 20. Ethiopian wheat breeds are vanishing in our eyes and we literally have the last chance to pick them. Most interesting is that these old wheat varieties can be found only in the loci indicated by Vavilov, but not in other places.

Author: Alexei Makeev