What Russian writers thought of the women's rights

/ Главная / Russkiy Mir Foundation / Publications / What Russian writers thought of the women's rightsWhat Russian writers thought of the women's rights

Tamara Skok

International Women's Day has been celebrated for over a hundred years, but the path to women's independence began much earlier. This topic was of utmost importance to the public. There were starkly differing views, and many swards were crossed over disputes about women’s rights and their role in public life.

Ivan Kramskoy. Woman Reading (Portrait of Sofia Kramskaya, the artist’s wife), 1863 (fragment). Photo credit: wikipedia.org

Russian writers and journalists did not stand aside and did their best to express their views on this urgent problem of women's personal identity. Vladimir Odoevsky was among the first to draw attention to the imbalances in girls' upbringing and criticized the prevailing social order. In his novel, Princess Mimi (1834), he wrote: “... blame, cry, curse the corrupted customs of our society. What is to be done if the only aim in life a girl in court circles has is to get married! If she hears from the cradle, “When you get married!” She is taught to dance, paint, play music so that she can get married; she is dressed, taken to the court; she is forced to pray to the Lord God so that she can get married as quickly as possible. This is the limit and the beginning of her life. This very life is hers. There is nothing tricky since every woman becomes a personal enemy for her, and she believes the key quality in a man is marriageability. Cry and curse - but not the poor girl."

It took a long time for the questions to become imminent, and a broad societal conversation broke out after Mikhail Mikhailov had published his article “Women, their upbringing and significance within the family and society" in 1860. According to the author, “only a radical transformation of women's upbringing, social rights of women and family relations” can become “a salvation from moral instability, which, like an old age's illness, hurts modern society.”

The writer approached the problem solution in a very responsible way, tried to reason from the objective point of view taking into consideration the works of honored philosophers, and posed a number of questions to the readers: “To what extent does the society well-being depend on the equalization of the rights of men and women? How can this equalization be achieved? What can interfere with it within the scope of contemporary concepts and customs? How should a family be formed to become a lasting guarantee of the true success of society? What is the role of a woman in domestic and social economy? What kind of industry, what kind of art can be a woman's occupation? "

Mikhailov ended his article with the following words: "May a larger circle of people delve into these very questions and worry about them: the answer will be given by life itself." And life answered immediately.

The abolition of serfdom and the fall of the customary landlord lifestyle led to the fact that active and smart young women began to look for their place in the world, they wanted to get an education, be actively involved in everything and fight for their rights. Such terms as emancipation (from the Latin emancipatio - liberation from dependence) and suffrage became extremely popular, and women advocating these social values were called emancipates and suffragettes.

A lot of men didn't take to the new trends, and popular writers were no exception. Fathers and Sons, a novel by Ivan Turgenev, was published in 1862. One of the minor characters is Avdótya (Yevdoksíya) Kukshina, an emancipated woman. She is described without a hint of likeness. She is a pretentious talker neglectful of her appearance who often rushes about, her thoughts are confused, and her reasoning is discrete. The person who does not find how to be useful. The writer shows his attitude by describing the dwelling place of Madame Kukshina and her appearance in disgust – there are “papers, letters, thick issues of Russian magazines, mostly uncut, thrown on dusty tables” and “scattered white cigarette ends” everywhere. As to her looks, “There was nothing ugly in a small and inconspicuous figure of this emancipated woman, but the expression on her face gave an unpleasant impression to the person looking at her." And she goes around "somewhat disheveled, in a silk, not quite neat dress," and her gloves are dirty.

Nikolai Leskov also stepped in and expressed his point of view on the problem in “Russian Women and Emancipation”, an article published in1860. According to him, women needed to be provided "with the opportunity to get all-around education, to follow their calling, to be assigned to the positions where they could earn the money that every person needs to support themselves and their families.” Referring to the formal right of women to independence, the writer regretted that in fact this right was violated every now and then: “An unenviable place has been given for a woman writer, a woman artist, and even less a woman scientist in our country. Speaking of women authors, society ridicules them: “Authorlings! Authorlings are coming!” And if women show a certain urge to learn, then they say, “Bluestockings! Professors, pedants!” Our society does not need such women.”

Dmitry Pisarev, a literary critic, also spoke up for the tender gender. In the article "Female character types in the novels and stories of Pisemsky, Turgenev, and Goncharov" (1861), he wrote: "A man oppresses a woman and slanders her... A man who constantly demoralizes a woman with the oppression of his strong fist, at the same time constantly accuses her of being mentally underdeveloped and lacking one or another noble virtue, as well as of proclivities to one or another maleficent vulnerability... The woman is not to be blamed for anything. She is the one who suffers all the time, she is a victim."

The critic made attempts to find an excuse for poor maternal influence prevailing in Russian families: “Our Russian mothers are not good in bringing children up, I agree; but where could they learn the sound pedagogical methods? Where could they be imbued with human ideas? Our mothers are busy arranging their coiffure or pickling mushrooms, - again, I agree. But what should they do when they don't know anything better? And they do not know because no one spoke to them properly. Only men are to be blamed for this because men conduct the orchestra of public opinion and are lead singers. If something goes wrong, they are responsible for it and should blame themselves."

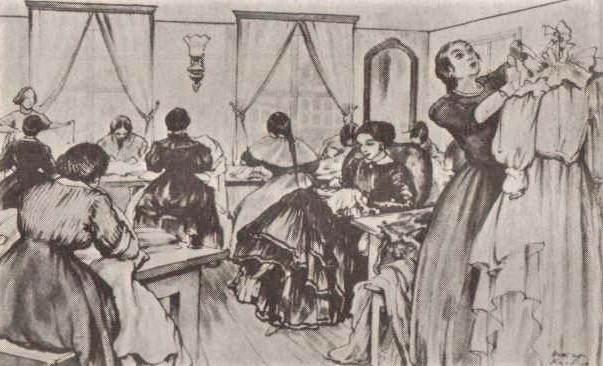

Workshop of Vera Pavlovna, illustration for What Is to Be Done?, a novel by Chernyshevsky. Photo credit: wikimedia.org

These are arguments and disputes, but how to solve the problem? Well, in terms of popularity and immediate relevance, nothing beats What Is to Be Done?, a novel by Nikolay Chernyshevsky published in 1863, where the ladies were given a simple and effective recipe for gaining independence. Many of the writer's contemporaries took the advice and put it to action, and living as women's communes became a good alternative to the unenviable social roles intended for girls by the social framework back then. Interestingly, in his novel Smoke (1867), Turgenev could not help but made an ironic remark about the women's sewing workshops inspired by Chernyshevsky's novel, and brought the following dialogue between Bambaev (an enthusiastic "always penniless" fellow) and Suhanchikova (nervous and an unlikeable childless widow):

“- I don't read novels anymore.

- What’s the reason?

- Because time is different now; my mind is occupied by one thing only: sewing machines.

- What machines?

- Sewing, sewing ones; each and every woman needs to stock up with sewing machines and form societies; that way they will all earn their bread and suddenly become independent. Otherwise, they cannot free themselves in any way. This is an important, important social issue.”

Explicit or covert resistance of men is quite understandable: the emancipation of women is usually accompanied by the 'feminization' of men, and this is a direct threat to the patriarchal order.

Leo Tolstoy rejected flatly women’s self-dependence and had a very narrow-minded view of the issue. In 1870, he wrote: “There is no need to come up with any solution for women who gave birth and have not found a husband: without offices, departments, and telegraphs these women are and have been in a demand exceeding the offer. They can become midwives, nannies, housekeepers, women of easy morals." It sounds pretty cynical, doesn’t it?

Ivan Goncharov discusses the side effects of secular education at the beginning of the 19th century in the article "A Million of Torments" (1872) featuring his review of Woe from Wit, a comedy by Alexander Griboyedov. He wrote: "French books ... piano ... poetry, French and dancing – they were believed to make up the classic education for a young lady. And then “Kuznetsky bridge and endless new dresses”*, dancing parties... and this society was the very circle that confined a young lady’s life. Women learned to imagine and feel only but not to think and know. Thought was silent, only instincts were expressed. They derived worldly wisdom from novels, stories - and that was the reason the instincts developed into ugly, pitiful, or stupid characteristics, such as dreaminess, sentimentality, the search for an ideal to love, and sometimes even worse. While being in such a hypnotic stagnation, in a hopeless sea of lies, the majority of women were outwardly dominated by conventional morals; and in the absence of healthy and serious interests, their lives were quietly swarmed with those novels that had become the base for the “science of tender passion." According to Goncharov, changes seemed to be all around us, but the status of women in the family and society had not changed much over the fifty years after the publication of Woe from Wit.

Mikhail Petrov. The boarding school students. The first cigarette, 1872. Photo credit: artwallpaper.narod.ru

Fyodor Dostoevsky was not immune to the question of women’s rights. He did support emancipation but was against revolutionary measures in this noble goal. Rightly believing that society was not yet ready to perceive the ideas of equal rights for women and men in a sensible way, the writer was confident that gradually this social issue of critical nature would go away of its own accord. It was required just to wait until changes in public consciousness take place.

Dostoevsky published his article “Models of sincerity” in Vremya, a monthly magazine. He defended a woman who fell into disgrace for daring to publicly recite Pushkin’s Egyptian Nights: “We do not yet have such rights for a woman. I do not mean that there should be no such rights; on the contrary, I stand for women’s rights with all my soul. I only say that there are no such rights for the time being ... This ideal freedom to exercise her rights has not yet been given to a woman. It will be established when society is established and moral rules in society are strengthened, then a woman will be allowed to admire a work of art aloud without being punished, to be inspired by the purest, highest artistic delight when reading it, and this pure woman will not be suspected of voluptuous thought when her eyes are intoxicated with artistic enjoyment."

Fyodor Dostoevsky also advocated the purity of terminology, trying to free emancipation from the negative undertone imposed by some conservative publications. So, in the article "Answer to Russkiy Vestnik" he wrote: "What do you mean by emancipation? In these disputes, we must first come to terms, agree with one another on basic points, in order to then understand each other. If by emancipation you mean the right of every woman to put horns on her husband at every opportunity, then, of course, you are right in your hatred to emancipation. But we have never understood emancipation in this way. For us, emancipation comes down to Christian benevolence, to education in the name of love for each other - love that a woman has the right to demand for herself as well. In our opinion, the whole emancipation-related issue comes down to the usual and ever-present question of progress and development.”

As time has shown, Dostoevsky was not mistaken. It cannot be said that the question of women's rights has been finally resolved in the best way, but the gloomy predictions, fortunately, did not come true. Women have done and are doing a lot of work improving themselves and the whole world, creating the future,j and raising children in union with those men who believe in them.

*A quote from "Woe from Wit" by Alexander Griboyedov

New publications

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.  Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.

Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.  When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.  Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."

Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."  "Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...

"Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...