Bunin’s Strict Artistry

/ Главная / Russkiy Mir Foundation / Publications / Bunin’s Strict ArtistryBunin’s Strict Artistry

Tamara Skok

150 years ago, on October 22, 1870, Ivan Bunin was born. He was a Russian poet and prose writer, winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature, honorary member of the Russian Academy of Sciences, emigrant and one of the most sophisticated and unbiased witnesses of his turbulent time.

“Damned Mongols…”

The memories that Bunin left of his contemporaries, fellow writers, are not the brightest ones because he approached them with strict creative and human standards. His views became even more rigorous when the Cursed Days began in the history of Russia. There are monstrous portraits made with strokes under this eloquent name in his diary entries. They are so distinctive and recognizable that you take a new look at some well-known writers.

Ivan Bunin. Photo credit: polit.ru

Here are some of Bunin's sketches: “About Valery Bryusov: His views are becoming increasingly left-wing ones: he is almost a typical Bolshevik... It is not surprising. In 1904 he gave ample praises to the Caesarism... From the beginning of the war with the Germans, he became a jingoistic patriot. Now he’s a Bolshevik." Aleksandr Blok also got his share, and more than once. Bunin criticized the poet for his pro-revolutionary position and said his poem "Scythians" to be a gross imitation of Pushkin's "To the Slanderers of Russia." After reading newspaper reviews about "The Twelve", Bunin was indignant: "Blok perceives Russia and the revolution like the wind ... Oh, phrasemongers! There are rivers of blood, a sea of tears, but they don't care."

Writers' circles and associations for him were "a new literary meanness, the line which is the limit", and he described them accordingly: "Musical snuffbox" is the most disgusting tavern, where "poets and fiction writers (Alyoshka Tolstoy, Bryusov and so on) choose the most obscene of their own and other people's works and read them” to speculators, cheaters and prostitutes.

Bunin could not accept the fact that in the new reality anyone could easily become a great poet or writer. It was enough to proclaim oneself as such, just as Igor Severyanin had done, or to believe newspapers and magazines all glorifying Gorky as the first proletarian writer: “How to stay calm when you can advance to be genius so easily and quickly? And everyone is so eager to win through, make everybody speechless, and come to the front."

Bunin saw everything happening in the country in general and in literature in particular as something related to the tragic times of enslavement and trampling upon Russian culture: “Aleksey Tolstoy once wrote: “When I remember the beauty of our history before the damned Mongols, I want to throw myself on the ground and roll out of despair.” It was only yesterday that Russian literature had many Pushkins and Tolstoys. And now the vast majority there are “damned Mongols” only.” Such a hard attitude could be explained by extremely high demands Bunin used to place on literary activities. He was hurt to see that the high standard set by truly great Russian writers and poets was deteriorating and trampled to the laughter and roar of poets like loud and insolent Mayakovskiy with mouths like a "trough”.

Bunin’s intransigence may seem kind of extreme today: after all, literary experiments of the Silver Age were not an outrage against the great Russian literature, but a search for new ways, a kind of getting rid of coarse realism and narrow-mindedness. Modernist poets and writers, including Bunin, made a real revolution in Russian literature. And if it had not been for the Bolsheviks coming to power, perhaps, Ivan Bunin would have been more tolerant to the developments back then. However, overlapping of those events and the end of the Russian Empire made him merciless in his views. By no will of his own, Bunin became the last keeper of the Russian literary tradition, and he was impeccable in this role.

It is understandable why Bunin did not like shocking Mayakovsky: he was all about poetry groundbreaking, provocative appearance, defiant behavior, violation of rules and norms. And his disgusting yellow jacket! And the piano suspended upside down from the ceiling over the stage! And bullying of the public who came to listen to the futurists! It became clear later that the numerous literary trends of the Silver Age had not been of destructive nature. They set the stage for a new era in Russian literature. Yes, the big is seen from a distance. But Bunin was the last splinter of Russian classics, and that splinter was as sharp as a razor.

The group of Russian writers. Sitting (from left to right): Maxim Gorky, Ivan Bunin, singer Feodor Chaliapin, Stepan Skitalets (S. Petrov), Nikolai Teleshov. Standing: Leonid Andreyev, Evgeny Chirikov.

Photo credit: granates.ru

The Chosen Ones

Bunin pointed out only two contemporary Russian writers as his like-minded ones - Tolstoy and Chekhov. He acknowledged their unconditional authority and at the same time felt belonging spiritually to the beliefs preached by them, the main of which was truthfulness.

Leo Tolstoy proclaimed that "there is only one thing needed in life and in art - not to lie" and wanted his readers "to be sensitive, so they could sometimes have sincere compassion and even shed a few tears." Tolstoy rejected modern poetry that experimented with meanings, images and sounds; nevertheless, he made an exception for Bunin's poems. Probably, he was attracted by keen simplicity and properly defined reality in Bunin's lines resonating with Tolstoy’s feeling and observations:

No birds in sight. The forest withers slowly,

Resigned to utter emptiness and chill.

No mushrooms, but there comes from out a gully

Of mushroom damp the strong and tangy smell.

The scrub is lighter and less tall, the greying

Grass near the bushes droops, seems trampled down;

Beneath the autumn rain the leaves, decaying,

In mouldy heaps lie of a darkish brown.

But in the fields the wind is fresh and biting.

I lead my stallion out and ride from home,

And, in the freedom of the steppe delighting,

Far from the villages till nightfall roam.

Lulled by my mount's slow, easy pace, I listen

With joy-tinged, quiet sadness to the hum

Of wind as it invades with singsong whistle

And drawn-out moan the barrels of my gun.

It was very important for Bunin to associate himself with Tolstoy, to check with him, to feel a spiritual commonality. It is not a mere coincidence that Bunin devoted several years of his life in exile to The Liberation of Tolstoy, the book that is still considered to be the best description of the complex creative and human ascent of the great classic.

Tolstoy's perception of the world could not but influence Bunin's views and, as a result, approach to writing. So, in addition to the both writers’ commitment to give a true picture of life, literary scholars find one more similar theme - death as the final test, a landmark event to determine the value or insignificance of someone who passed away. This idea is not new, but everyone perceives it in terms of his/her own life path. Repeating Marcus Aurelius’ words that “our highest purpose is to prepare for death,” Tolstoy wrote: “You are constantly preparing to die. You learn to die better." But this high philosophy is still strange to most people. So Bunin’s Gentleman from San Francisco failed this test of death.

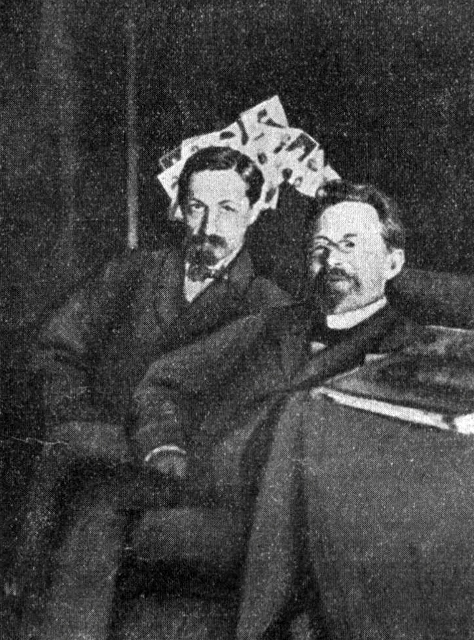

Ivan Bunin and Anton Chekhov. Photo credit: wikipedia.org

Bunin was a devotee of Chekhov's short stories and novellas, but he confessed that he “did not like” plays. Chekhov witnessed development of Bunin's talent and predicted his future success. The writers communicated cordially and held friendly correspondence. Bunin stayed in Chekhov’s Yalta house even when he was away and sent touching letters from there. Here is one of them dated January 13, 1901: “It is very quiet here, the weather is mild, and during these days I’ve had wonderful rest in your house. I cannot have enough of the blue bay at the end of your valley. In the morning my room is full of sunlight. And your office, where I sometimes go to walk on the carpet, is even better: it is fun and spacious; the window is large and beautiful; there are green, blue and red reflections on the wall and on the floor, they are the brightest when the sun is shining. I love colored windows, they seem gloomy only during the twilight hour; and the office is empty and lonely during the twilight hour, and you are far away… I heard from Maria Pavlovna that you are working - I really wish you to have true inspiration and balance. I also scrabble and read something. And on top of all of this, I live quietly and nobly. I send you my warmest regards."

Chekhov, as a big brother, often wrote letters in a friendly and joking tone. Thus, in March 1901, he wrote: “Dear Ivan Alekseevich! I'm not bad, so-so, feeling old. Nevertheless, I want to get married." On January 15, 1902, he sent Bunin the following letter with congratulations: "Dear Ivan Alekseevich, how are you? Happy New Year! I wish you to become famous all over the world, to get in with the prettiest woman and win 200,000 on all three loans." As a joke, Chekhov called the nobleman Bunin Mr. Marquis Bukishon; and Bukishon was entrusted with innermost thoughts and things that bothered Chekhov's soul or occupied his inquisitive mind.

The writers also shared their respect to Tolstoy. Once, Chekhov told Bunin with his natural irony that he admired Tolstoy's contempt for “all other writers”: “He believes all of us ... to be absolutely nothing. He sometimes praises Maupassant, Kuprin, Semyonov, me ... Why does he praise us? Because he sees us as children. Our stories and novels are infantile pastimes for him... Well, Shakespeare is another matter. He is an adult and annoys him, because his writing manner is different from Tolstoy’s one.” And in another conversation, Chekhov prophetically declared: “When Tolstoy dies, everything will go to hell!” – “You mean literature?” - "Yes, literature as well."

In addition to prominent, great and authentic talent, Tolstoy, Chekhov and Bunin also shared the sense of identity and independence of thought. They understood the level of their talent and the related responsibility to the present and future.

In the grip of extreme sensibility

Attentive readers of Bunin's works notice his manner of describing the most subtle shades of colours, sounds, and especially scents. The scent palette in some works prevails over events.

Antonov Apples, for instance, is a good example of the above. The book’s name indicates the dominant aroma, but it also contains a lot of others: there is “the scent of honey and autumn freshness” in the garden, “the smell of tar is in the fresh air”, “and here's another scent: there is a fire in the garden, and fragrant smoke of cherry twigs comes along".

Stories about tragic love have similar approach: they show a scene through the eyes of a man, and scents add colors to it. “Sunstroke” describes heat, stuffiness, hot air and maddening "smell of her suntan and linen dress." In "Natalie", there is a sweet contentment flowing in the surrounding nature and in a young body: in the daytime "air sweetened with flowers and herbs" was penetrating through the shutters, "wind sweetened with rain in fields" was blowing in the evening, and "sweet scent of flowers" filled the night, the heart was sinking in the “sweet and mysterious way." And prior to the meeting after a long separation, the hero had a strong sense of "freshness and novelty of ... field and river air", the echoes of unforgotten teen-age romance could be heard in the delicate evening chill: “there was strong scent of sweet pear blossom."

The poems also have the same visual sketches filled with scents. Sometimes they are bright. For example, boulders in the coastal area "glisten in the sun with their wet sides", there is "autumn wind, the smell of salt and noisy flock of seagulls." And sometimes they are subtle, like the “delicate scent of beads” inhaled by monks looking at the world “from behind discoloring to black bars” (“Sunset”).

Those who knew Ivan Bunin closely mentioned that his sense of smell, hearing and sight were very delicate by nature. The writer used to say that his extreme sensibility was the inner one. According to him, in his youth he was able to see objects in the starry sky, while others needed special optics to see them; he also was able to hear bells of horses while they were still a few kilometres away.

This extreme sensibility explains the quality of scene when Bunin described landscapes, human experiences, and events. Some researchers believe - and for good reason - that Bunin's texts are very cinematic.

Russian exile

In 1933 Swedish Academy awarded Ivan Bunin with the Nobel Prize for Literature "for the strict artistry with which he has carried on the classical Russian traditions in prose writing." Strict artistry is a very correct definition, because Bunin's style comprised of clarity of thought, power of feelings, as well as classical accuracy and harmony of language. This fully applies to both prose and poetry of Bunin, including his earliest works. He mentioned in his diary: “I reread some poems by Aleksey Tolstoy - a lot of them are surprisingly good; and I reread my “Selected Poems”. How come they were not appreciated is beyond my understanding!"

The last bitter remark refers to the period when Bunin was denied his authenticity and associated with the decadents, poets of a melancholic type. Indeed, Bunin's poems faded away when contrasted with poetic research and vivid experiments in the field of sound painting, color painting and etc. by the symbolists and other representatives of modernism. But time has sorted everything out.

According to Vladislav Khodasevich, Bunin's works stand out for “the very process of seeing, the process of intelligent vision, rather that speculation about the visible”. Getting a Bunin-style strict, simple and harmonious outcome required meticulous work both at the writing stage and after that. It is known that Bunin could make editorial changes during the page makeup process and performed rigorous proofreading: it was important for him to see that every word and every punctuation mark were in proper places.

While in exile, Bunin finally took the rightful place at the top of the literary Olympus. When the Swedish Academy asked him to specify his nationality before the Nobel Prize was awarded, he wrote a proud yet bitter status: "Russian exile." He did not keep the prize money for retirement. Bunin gave nearly everything to those in need: he sent money to people who had asked him for help in numerous letters; he helped his fellow writers who had faced difficulties, because he knew very well about hunger and need in a foreign land.

Ivan Bunin made the following entry in his diary: “I was intelligent and once again intelligent, talented, inconceivable due to something divine which is my life, due to my personality, thoughts, feelings – can all those things disappear? No, that’s impossible!" This reasonable self-esteem reminds of Pushkin's confident statement: "Not all of me will die – my soul lives in my lyric /Which will outlive my dust, outrun my putrid reek."

New publications

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.  Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.

Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.  When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.  Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."

Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."  "Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...

"Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...