“I will rigidly call to account for losses.” Rodion Malinovsky’s path from a soldier to the Marshal of the USSR

/ Главная / Russkiy Mir Foundation / Publications / “I will rigidly call to account for losses.” Rodion Malinovsky’s path from a soldier to the Marshal of the USSR“I will rigidly call to account for losses.” Rodion Malinovsky’s path from a soldier to the Marshal of the USSR

In the lead-up to the Great Victory anniversary, Natalia Malinovskaya, the daughter of the legendary Soviet military leader Rodion Malinovsky, told the Russkiy Mir about her father, who had worked his way from being an ordinary machine gunner of the First World War up to the Soviet Marshal and Minister of Defense of the USSR.

– There’s a well-known proverb: “It's a poor soldier that never wants to become a general”. Natalia Rodionovna, what about your father, who became the Marshal of the USSR? Did he also aim high while being a soldier?

– Back in World War I, when my father was the youngest soldier among the wounded in a field hospital in Poland, a fortuneteller predicted him an outstanding fate: the Marshal’s baton and the highest military post. Just imagine, what fun the whole room had hearing it. Another gypsy warned: “Do not break new ground, do not hit the road on Friday! It’s a bad day for you.” And my father recalled that he had been wounded on Friday, but at first he didn’t take the warning seriously – that could be just a coincidence! However, after being wounded the second time (also on Friday, just as the third time, thirty years later) he made it a rule to look at the calendar. And at the war, scheduling beginning of operations (unless, of course, it depended on the Headquarters) or planning service-related trips, he did his best to avoid Fridays. But you can’t exclude it from the week - and all worst things in our family inevitably happened on Friday. Friday was also the last day of my father’s life - March 31, 1967.

Rodion Malinovsky, the Marshal of the USSR, ceremonial portrait, 1945. Courtesy of Natalia Malinovskaya

I can assure you that neither career upswing nor art of war in general were among my father’s life priorities. And the word “career” was not in the vocabulary of people back then. It ticks me off as well: a person needs an occupation, not a career, which can be acceptable only as a result of good performance in his/her occupation.

My father could and wanted to take a try in another field, or even fields. However, he did not regret that fate had brought him this way and not otherwise, he simply knew that he would have managed any other occupation and quite well. Sometimes it even seemed that he was evaluating other professions, since he was looking into them hard, with attention and interest.

In the last year of his life, I asked my father: "What did you want to be?" And he said: "A forester." I think it was true, though related to that very last year only. A forester was his late utopia. It was deeply harmonious with the person who had gone through the mill. That is the way my father was in my memory. I know one thing for sure: if forestry had become his work, he would have studied life of the taiga with the same eagerness and passion, as he did with ancient strategists. But in his young years, of course, he would have answered differently as his hot-tempered and adventurous nature did not tolerate life of a hermit.

There was another, probably the major point of interest in his life - literature. I’d rather say it was untapped calling.

While recovering in the hospital in France, my father wrote a play about Russian soldiers for the amateur theater, which was arranged by those recovering. They even began rehearsals, but there was no premiere, and it was not a matter of staging. That text, of course, was not preserved. But it is interesting that my father gave his intention a second chance. In 1920 he was recovering from typhoid fever in a hospital in Russia. A play about uprising in the La Courtine military camp was written there. And he kept that manuscript, though did not entertain any literary illusions.

My father had hardly anything left from those times, and this is not surprising. However, things he carried through three wars – the Civil War, the Spanish Civil War and World War II – included that manuscript, a service record book of a machine-gunner of the 256th Yelisavetgrad Regiment and a few faded photographs, including the ceremonial one with Cross of St. George, as well as a French pocket letter book with golden edging in magenta embossed leather.

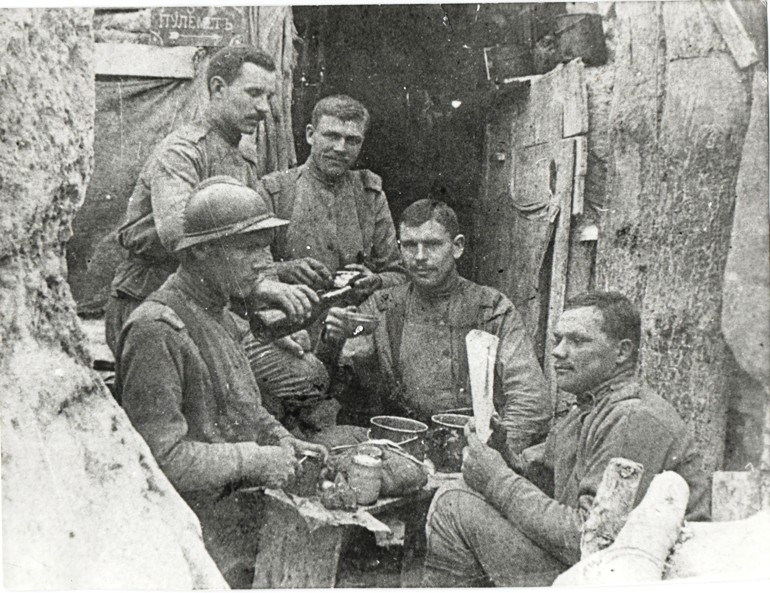

Rodion Malinovsky (in helmet) among soldiers of Russian Expeditionary Force in France, 1916. Courtesy of Natalia Malinovskaya

Forty-two years later, in 1960, during a service-related trip to France, my father visited places where his troop unit had been restructured. Meeting with youth had a variety of consequences, and I’ll mention just one of personal background: six months later, a notepad with “characters” appeared on my father’s desk, as well as a thick notebook, the first of eleven, with the very beginning of a novel.

My father was fascinated by new work, which he performed by bits and starts – at nights and weekends.

Eleven thick notebooks filled with a graceful, old-fashioned handwriting. There were absolutely no crossing outs; every word was well-thought-out and matured. The first page has the date “December 4, 1960” and the note “Sample plan (outline)”. The last notebook was completed in the fall of 1966.

– There were several wars in Rodion Malinovsky’s life: World War I, the Civil War, the Spanish Civil War and World War II. “Coronel Malino” – that was how soldiers of the Spanish Republican Army called Colonel Malinovsky, military adviser to the Central Front, during the Spanish Civil War. Tell us, please, about that period of his military service.

– The Spanish war, like any war, was an overwhelming grief - it broke up families, broke up friendship ties, and ensanguined the country. However, that war had a high and clear note, which the human heart could not fail to hear. It was that very note that people of good will responded to.

The Spanish Civil War was recorded in our military personnel’s files as a service-related trip without indication of duty station. But, just like those whose decision depended only on themselves, they went to Spain at the behest of their hearts and fought there not for Spanish gold, which they had no idea about, and not for Stalin's world domination. Spain was a pure deed (let us quote Hemingway) for the Soviet military, just as for all interbrigadists, and it became a lifelong memory, a bitter and bright one for each of them.

So it was for my father. There was a double folded pass in the cover lay of his last notebook. It was a dark pink cardboard with arms of Madrid in the left corner, large inscription “Unrestricted entry everywhere” in the middle, fine print “with the right to bear arms” underneath followed by “permitted by Malino”. Then there was the seal, date: May 26, 1937 and signature of the military governor of Madrid.

Colonel Rodion Malinovsky (left) and Hans Kaale, commander of the Interbrigade, on the Central Front. Spain, 1938. Courtesy of Natalia Malinovskaya

In Spain my father was appointed as an adviser to Enrique Líster, one of the best commanding officers of the Republic. No one was able to get on with him. Líster was a gutsy, talented young man, who had got education in the same academy as his adviser did. When they met first, he greeted his new comrade-in-arms cautiously, even defiantly, and then suggested him to walk along the battlefront to inspect the situation in person. The walk under the fire lasted until a hat was shut through, just as in a musketeer novel, and Líster himself saw total self-control of the adviser who had been a soldier in two wars.

Obviously, my father understood Líster’s intention to test him, as well as pointlessness of bravado; but he also understood that if proposed conditions were not accepted, professional cooperation would not be possible. So finally they got on really well.

– During the World War II Rodion Malinovsky commanded the Southern, 3rd and 2nd Ukrainian Fronts, developed and carried out many operations that were recorded in the history of military art. According to the country’s leaders and military commanders, he had high military calling. Concept of each operation included some kind of unexpected method of action, and he was able to mislead the enemy with a system of well-designed measures. Did you discuss famous operations of your father with your family?

– I know of the operations elaborated and carried out by my father, of course, not from him, but from his friends and comrades-in-arms who I spoke to when my father had passed away. Many aspects were common for all the stories.

For example, there were two mandatory requirements that my father included into every appointment instruction. Here is the testimony of Lieutenant General A. I. Malchevsky: “When I arrived at the control of the Commander of the 2nd Ukrainian Front, Rodion Yakovlevich said: “You are taking command of a division level unit that has suffered heavy losses - they didn’t try to save people, and it is unforgivable. You have a double task - to accomplish the mission and save people. The commander’s first duty is to protect soldiers, skillfully providing them with covering fire. Remember this when preparing the offensive operations. I will rigidly call to account for losses. If artillery and mortar fire is sufficient, do not send people there." By the way, this is exactly what Rodion Yakovlevich did during liberation of Austerlitz (now - Slavkov u Brna). A powerful fire strike was directed to the city park center, where the enemy’s headquarters and reserves were located. In such a way, civilian casualties were avoided and human losses were minimized.”

The second requirement came up in the last year of the war – all those serving at the 2nd Ukrainian Front knew that the non-looting order was rigorously complied there.

All memoirists say that my father’s concepts were unorthodox. I’d like to quote General Belov’s memoirs about Zaporozhye night assault, which was carefully worked out to the last detail and was unprecedented in scope of participating troops — three armies and two corps: “Only a commander who knew the enemy well and had confidence in his subordinate commanding officers and troops could decide to go for night assault on a large city. Why were we in favor of the night offensive apart of common advantages of a night battle? First of all, it was about gaining the indisputable surprise and about scale, which required pinpoint precision this time. The German command did not even suspect that our entire Front had launched the offensive; they failed to find their way around and maneuver with reserves. And we cut our way to the city: by the middle of the night, the second defensive perimeter was battled through. The breakthrough was led by the tank corps followed by the Russiyanov Mechanized Corps. By dawn, our troops were near the city limits, and in some areas they were already fighting on the streets. The Zaporozhye assault launched by the Front troops at 10 p.m. on October 13 was completed by 1 p.m. on October 14 with total liberation of the city. Such surge operation of the troops saved Dnieper Hydroelectric Station from the complete destruction."

The battle for Zaporozhye (battle near the Dnieper Hydroelectric Station). Photo credit: trendsmap.com

I wanted to mention the Zaporozhye assault, because this page of the war is largely unknown to the broad reading public. Though, of course, the Jassy–Kishinev Offensive is also known, perhaps, only by students of military academies, given that it was an amazing operation in each and every aspect – be it attrition ratio (ours was ten times less), huge conquered area, or withdrawal of a Germany’s ally, Romania, from the war…

– After military operations in Europe, Malinovsky took command of the Transbaikal Front, which was assigned the main role in defeat of the Kwantung Army in August 1945 ... What would you highlight in that period of Rodion Yakovlevich's life?

– I suppose, prowess. However, it does not relate to my father only or to his entire Transbaikal Front only. By August 1945, everyone who fought in the Japanese War, from a soldier to the Commander-in-Chief of our troops Marshal Vasilevsky, had gained the hardest experience of four previous years and learned a lot. After all, speaking of 1941, we forget that before that time Germany already walked through the whole Europe, and even earlier it had tested considerable part of its forces in Spain, which had a great significance. Indeed, those of our commanders who had been in the Spanish War, including my father, fought much better during the first months of the Great Patriotic War than those, who did not have any experience of modern war. Experience gained in the First World War and the Civil War was no longer relevant for the World War II. And, speaking of the Japanese War, apart from the experience and skills paid for by blood, elaborate pre-war preparations were very important - staff targets and well-thought-out plans of operations

So, there was the Japanese Kwantung army of 700 thousands against our 400 thousand soldiers. And conditions were very much unlike European ones - different climate, different landscape and different people - their military behavior was so dissimilar to European! “You never know where you are with them...”, the war veterans recall. The Japanese could only be caught unawares; it is called the element of surprise in military parlance. And that exactly how things happened.

No one in the entire Kwantung army would be capable of assuming that our troops could drop from the Khingan Mountains. And this is exactly how troops of the Transbaikal Front came to the theater of military operations - from the rear, which had seemed to be absolutely safe. However, reaching there required ability to fight in the mountains (my father’s Front had such experience in the Alps and Carpathian mountains) and even bring tanks through mountain labyrinths, which no one had done before.

And what about our assault forces? The story of them taking the puppet Emperor Puyi as prisoner could be the page from Three Musketeers!

Nevertheless, the most alarming was the news that the Japanese had plague laboratories. After all, any fanatic (and their number in Japan was much greater than in Europe) could break at least one test tube out of despair or in the face of captivity, and the plague would break loose and spread without distinguishing between the front and the rear, massively sweeping people away just like rubbish, be they victors or conquered. Those laboratories, working with plague, typhoid, anthrax, cholera and other deadly infections, had to be neutralized. And that was done by our soldiers - in no time and brilliantly - with flash-like landing, having taken by surprise both the guards and the personnel. Once again they saved the world, this time literary from the plague. Today, this story, I think, should be particularly impressive.

– What did appointment to the post of Minister of Defense of the USSR mean for Rodion Yakovlevich?

– Responsibility. It was a huge responsibility and understanding that there were extremely difficult issues, not just the military ones, which required to be dealt with immediately.

My father’s appointment was a surprise to everyone (shortly before he was just a Far Eastern provincial!). And, apparently, it was a surprise for him as well. My mother shared that the day in October when his appointment became known was among the most difficult ones.

My father came home as black as night, did not have dinner, and said: "Let's go to the summer house." He did not say any single word on the way. And he did not say any single word while having a long walk, until it got dark. Mom sensed the situations when questions had to be avoided. Finally, my mother’s brother came out to the porch: “Rodion Yakovlevich, the radio news reported you had been appointed a minister!” And here my mother failed to keep silent:

– Why didn’t you reject?

– How could I reject?

And nothing more was said.

My father took on new duties with a heavy heart. I will not speculate why, I do not want to think up anything. Perhaps, he realized how great responsibility was it and foresaw difficulties of all kinds. As to attitudes, Alexander Mishin, his adjutant, told me that shortly after the appointment, my father was concluding the party conference, where, as usual, former flatterers had smeared Zhukov with a lot of garbage. And he clearly said that removal was not equivalent of civil execution and not a reason for jeers: "No one can deny accomplishments of Zhukov."

As a minister, my father had to stand up for his own – dissenting - opinion time and again.

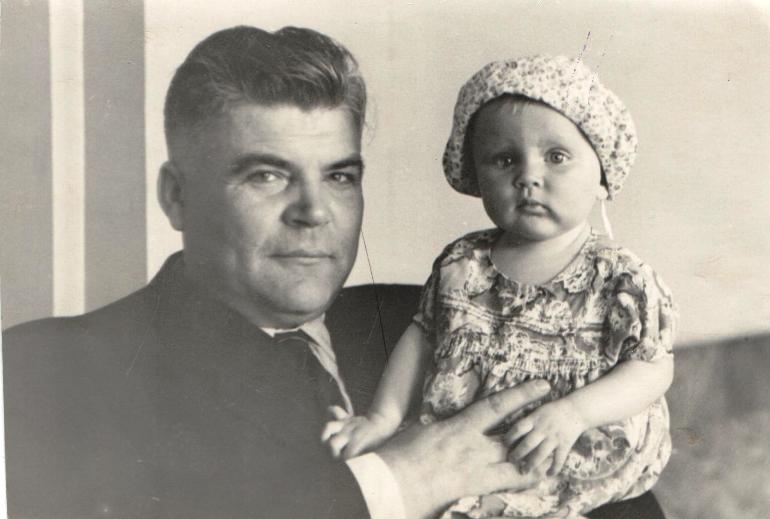

Rodion Malinovsky with his daughter. Family archive. Courtesy of Natalia Malinovskaya

Everybody understood that postwar staff redundancy was a compelling need. But it was hard to explain those responsible for on-site redundancy that it should be conducted in more tactful and careful way. I don’t even speak about the authorities ranking above the Minister of Defense, and Khrushchev. I saw my father’s indignant resolutions on dismissal complaints: “What in the world are you doing when a person has four months left before retirement! Let him complete his service!” Piles of such letters were on his desk.

I can’t pass my judgment about difficulties of another kind — nonconcurrences with Khrushchev on certain issues. I only know that they did have them and in considerable amount. I believe the following phrase from Khrushchev’s memoirs is very significant. It relates to two important turning points in the military policy of the USSR when he listened to my father’s words. Here it is: “Appointing Malinovsky as the Minister of Defense, I was convinced that I was acting in the interests of the country, and I did not have to regret this decision. I will always be grateful to him for the fact that he twice kept me from the steps fraught with the third world war. "

It seems to me that these words speak a lot about both of them. It is natural to assume that one of the cases was the Caribbean crisis, but I can’t guess the second one.

Natalia Malinovskaya with her parents on the Victory Day on May, 9, 1965. Family archive. Courtesy of Natalia Malinovskaya

Back then, in the 1960s, on the way to parity, my father’s main concern was re-equipment of the army, and personnel trained in a different way were required for that. The record in his notebook of 1958 says the following:

“Currently we need military intelligentsia as much as air to breathe. Not just highly educated officers, but people who have mastered high culture of mind and heart, a humanistic worldview. Modern weapons of tremendous exterminatory power cannot be trusted to a person who has only skillful, firm hands. We need a cool head capable to predict consequences and heart capable to feel - that is, a powerful ethical instinct. These are the necessary and, I would like to think, sufficient conditions.” There’s a feeling that these words have been written today, isn’t there?

– Unfortunately, today we see that rather unfriendly steps are being taken abroad toward our country and its decisive contribution to liberation of European peoples from fascism. It happens contrary to the historical truth and relatively recent assurances of gratitude to the soldiers of the Red Army – just look, for instance, at the recent demolition of the monument to Marshal Konev in Prague... My guess is that it is very hard for the descendants of those soldiers and officers who fought and died for the liberation of Europe to perceive such things.

– My father’s trips (both official and with family) to the countries that back then were called the People's Democracies always started the same way: on the very first day, in the morning, we went with bunches of flowers to the monuments to our soldiers – we did it in Poland, and in Hungary, and in Romania, and in Czechoslovakia, and in the GDR. I am grieved to think how my father would respond to the events happening there, and not only there, but much closer.

And therefore, I was very happy to learn that there is a small town near Brno in Slovakia, were Russian language teachers, who lost their jobs some time ago, have established an absolutely informal friendship society. They come together once a week or once a month. They tell each other and everyone who drops in about Russian culture, about our art, classical and modern, about history, including those events that united our peoples 75 years ago.

Bust of Marshal Malinovsky in Brno (Czech Republic). Photo credit: wikiquote.org

Moreover, they have students who passionately study Russian language. For many years, I have been in correspondence with Anna Marachkova, a tireless enthusiast committed to friendship. She has been bringing large groups of students to Russia to show them our museums: the Tretyakov Gallery, the Hermitage Museum, the Russian Museum, and certainly - the Armed Forces Museum. And last May, she and her students went to Brno to lay floral tributes at the monument to my father, which had been installed there in 1945. I admire Anna's work and I am infinitely grateful to her for commemoration.

– You have a rather extensive public activity: the chairperson of the Association of Commemoration of Soviet Volunteers-Participants of the Spanish Civil War, the president of the Russian Expeditionary Force (1916–1918) Memorial Society... What are the plans of the organizations you head on a short-term horizon?

– Members of the Russian Expeditionary Force Memorial Society in France and in the Balkans include descendants of corps soldiers, historians, cinematographers, and research enthusiasts. Last spring, we managed to hold a conference, which brought together descendants of soldiers from various countries, as well as military historians. Some of them made presentations, others simply reported something or shared family memories, and it was great! As a result, extensive, wonderful material was collected. Our task now is to publish the conference proceedings.

Natalia Malinovskaya at the opening of the exhibition dedicated to the Russian Expeditionary Force. Courtesy of Natalia Malinovskaya

I also hope there will be another book, where the soldiers speak for themselves. It will include fragments or even full texts from their memoirs, as well as letters that the Expeditionary Force veterans wrote to my father in the 1960s. Those are valuable evidences, but there’s a huge work ahead: compiling the book, preparing the texts for publication.

Speaking of Spanish plans, I would like to do quite a lot next year (it marks the anniversary of the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War).

First of all, there will be an exhibition of my father’s photographs taken in Spain in 1937-38. In this case selection is inevitable - there are more than three hundred of them, and their processing is rather complicated since photographs are tiny. Secondly, there is a book that I have been slowly working on for a long time - Spain of Coronel Malino. And, of course, I would like to finally have an exhibition dedicated to our volunteers in Spain at the Museum of the Armed Forces. I have been asking the Museum about it for more than a dozen years. They have such an amazing collection related to Spain! And one could still address families of the descendants of our volunteers and see what they have to show. I am sure that the Spanish Civil War Archive will help or even participate.

Songs of the Spanish Civil War Concert has been planned with the Moscow Conservatory and, more specifically, with Alexander Solovyov, the Chamber Choir conductor and the art director of the Tribute to Victory Day annual festival. A few years ago, we had a similar joint project - Favorite Songs of Commanders of the Great Patriotic War - to my adaptation. Well, there are some challenges here - you need to find music sheets, make arrangements... I hope they are not insurmountable.

New publications

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.  Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.

Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.  When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.  Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."

Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."  "Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...

"Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...