Thank you, Constantinople! What the fate of white émigrés in Turkey was like…

/ Главная / Russkiy Mir Foundation / Publications / Thank you, Constantinople! What the fate of white émigrés in Turkey was like…Thank you, Constantinople! What the fate of white émigrés in Turkey was like…

Svetlana Smetanina

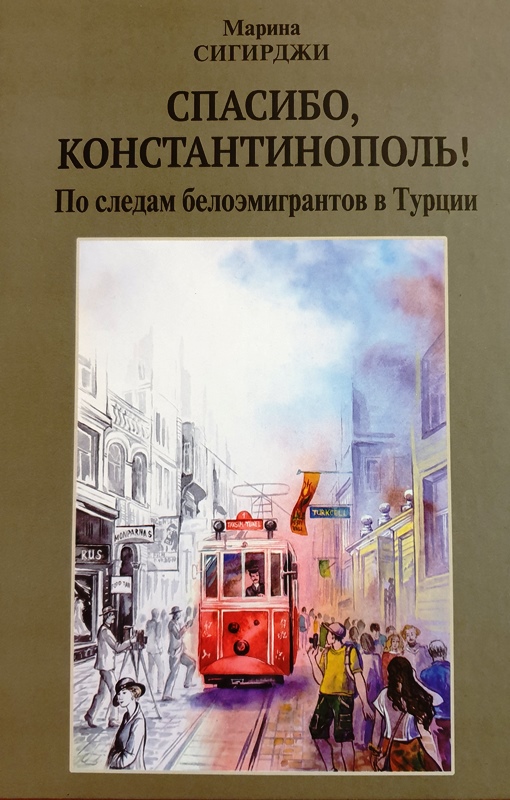

For a long time very little was known about life of white émigrés in Turkey. Although it was Constantinople that became the main transfer site for hundreds of thousands of refugees from Russia after the October Revolution and the Civil War. Perhaps this gap would not have been filled for a very long time if it were not for the selfless work of our compatriot Marina Sigirji. A few days ago she presented her book “Thank you, Constantinople! In the footsteps of white émigrés in Turkey” in the House of Russian Émigré Community.

Marina Sigirji moved to Turkey ten years ago. And she became interested in the history of this country. That interest in no time led her to the tragic chapters of history of her own homeland - Russia. “Having come across the old name of Gallipoli, I immediately remembered the following historical fact – “Staying in Gallipoli”. I began to read about that place and got a desire to go there. It is 400 km from Istanbul. There have been several of such trips,” the author said at the presentation of the book.

Thank you, Constantinople! In the footsteps of white émigrés in Turkey by Marina Sigirji

According to her, these essays are an attempt to look at the century-old events in the light of individual destinies of emigrants and their descendants, those who ended up in Turkey and stayed there for good. The book begins with the moment in 1920 when Constantinople was peopled with a large number of Russian emigrants. And it covers the entire life span of those who stayed in Turkey throughout the XX century.

It is commonly known that Constantinople (it was renamed Istanbul in March 1930) became the main transfer site for white émigrés and refugees from Bolshevik Russia as a result of mass evacuation from several Black Sea ports, such as Odessa in April 1919, and Novorossiysk in January and February 1920. The largest evacuation was conducted from Crimea in November 1920 and from Batumi in April 1921 after the fall of the Menshevik regime in Georgia.

Мarina Sigirji presents her book

The book contains the following chapters: historical background, Gallipoli and Çatalca, emigrants on Adalar (the Princes' Islands), Athos Metochions with family chapels in the Karaköy quarter, the Fukaraperver Humanitarian Aid Association, cultural life of white émigrés in Constantinople, Grande Rue de Pera, the main street of Istanbul, Russians restaurants, first beaches, lost destinies - true-life stories, necropolises in Istanbul and Adalar (the Princes’ Islands).

Turkish transit

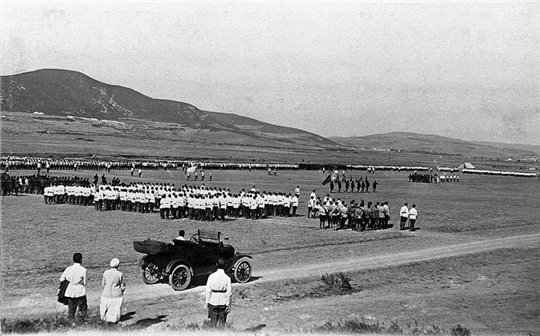

Going off on her journey to historical places linked to the exodus of the White Army, Marina Sigirji found a valley which had served as the campsite for the First Army Corps of the White Army for a year. “I just wanted to walk around this valley, feel wind flows of the “empty field”, as they used to call Gallipoli. Indeed, it was very cold. For the first time I came there in early October, and all the time I had one thought - how could they live in dugouts?”, she shared her feelings.

Gallipoli, a parade in the camps. Photo credit: ru.wikipedia.org

Surprisingly, even after almost a century, everything has remained just as it was before – there is a small mountain river drying up in summer, tousles of blackberries and many snakes. As if those hundred years had not passed. The author of the book found places directly related to Russian immigrants in a near-by town. The houses where the emigrants lived have been preserved, and people still live there.

Then Marina Sigirji visited Çatalca, which is 70 km from Istanbul. Once there were four Cossack camps. And in each of those places she met grave robbers looking for something to profit from. It turns out that Russian refugees used to hide their possessions, burying them in the ground. A hundred years later, there are those who are still looking for the treasures. And one of these diggers even showed the researcher where the Russian cemetery was located. He remembered about its existence since childhood, because there were iron crosses.

Commemorative cross. Photo credit: sammler.ru

Now those crosses are gone - locals dragged them away for their needs. There was also a farm, where some refugees lived and grew vegetables. There was also a church they had built. Now there is nothing left there - just a sown field, but elderly locals, who Marina Sigirji communicated with, shared a lot of stories about Russian refugees heard from their parents. And those stories are also in the book.

Most of Russian fugitives settled in Constantinople, but tried not to stay there too long. In her book, Sigirji cites data from the Istanbul Central Inquiry Office, showing how the number of white émigrés changed over time. At the end of 1920, there were 200 thousand Russian names registered in the Turkey capital. By March 1922, about 35 thousand people still lived there, and in September 1922 there were 18 thousand of them. By the beginning of 1926, about 10 thousand Russian emigrants lived in the city and its suburbs, and by the end of 1930 there were 2 - 3 thousand of them only.

“After the last and largest anti-Greek pogrom of 1955, a lot of refugees left for other countries. Currently I am working with emigrants' letters and one of them had the following phrase: “After the anti-Greek pogrom, we realized that we are unwanted here now. We are preparing documents for departure from this country,”said the researcher.

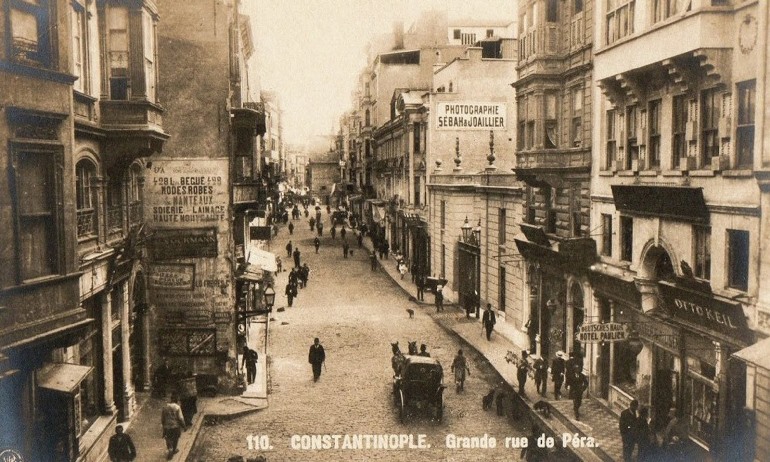

Residents of Grande Rue de Pera

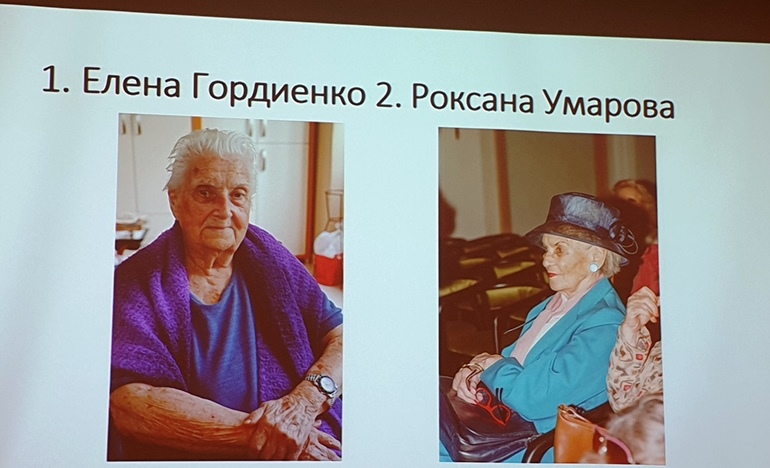

Nevertheless, there was a very small part of white émigrés who stayed and managed to preserve their culture, faith, and language. In her book, the author cites many Russian names that contributed to the culture and art of Turkey in the middle of the 20th century. Lidia Arzumanova was among those who did ballet - she opened the first ballet classes in Constantinople. Elena Gordienko was actively involved in establishment of the first state ballet school. This school was initially located in Istanbul, and then shifted to Ankara.

Nikolai Kalmykov, a portrait, landscape and icon painter, stood out of the artists’ community. His wall paintings in many Istanbul cinemas and its opera theater have been preserved.

Constantinople, Grande Rue de Pera. Photo credit: lcivelekoglu.blogspot.com

Back then most of Russian emigrants settled on the main street of Istanbul - Grande Rue de Pera. Foreigners took up residence there ever since Byzantine times. And later foreign diplomatic missions were set there. In the 1920s, there were Russian establishments in nearly every building. Entrepreneurially-inclined Russians, coming together in small groups, opened cafes, restaurants, cabarets, studios, bookshops, and grocery stores.

There is also the famous Flower Passage (or Çiçek Pasajı in Turkish), which also owes its name to Russian immigrants. It turns out that Russian young ladies were selling flowers on this street. And they used to hide from clinging Turkish admirersin the passage. Later flower shops were opened there. Also, Russians used to sell remaining jewels and gold in the passage.

The famous Black Rose Cabaret was located on this street as well. It was opened by a Turkish businessman specifically for Alexander Vertinsky. And there were also several Russian restaurants that worked for a very long time. They were the Petrograd Confectionery, the famous Karpich Restaurant, which later moved to Ankara at the request of the first Turkish president Kemal Atatürk. But theRégence Restaurant still operates and carries on the traditions established by its founders. It became a symbol of Russian Istanbul, as well as Istanbul in general. And when the Turks wanted to open their own restaurant at the same place and closed the Régence for a short while, the whole Istanbul public rallied in defense of the iconic establishment. It is remarkable that interior of the restaurant has mostly remained the same since that time - chandeliers, wood panels, mirrors on the bar counter. And the menu still has Russian dishes. The current owner, not being Russian, strives to carry on historical traditions and even learned several phrases in Russian.

Churches, certainly, were the spiritual bond for Russian émigré community. There were three Russian temples of Athos Metochion in Constantinople. Moreover, they were all located on the upper floors of three- and five-story buildings. Those were the Metochions of St. Andrew the Apostle, St. Elijah and St. Pantaleon. It was the place where the white émigrés felt alienation from their motherland the least.

In 1954, the Fukaraperver Humanitarian Aid Association was opened at those Metochions to help poor people of Russian origin. It was founded by Alexander Nasonov, who contributed 40 thousand Turkish liras, a very significant amount back then. His portrait can be seen in a Greek chapel of the largest Greek cemetery, where Russians were buried.

“The Association helped in many ways, not just with money. They helped to find accommodation, organized Russian dance night parties and Christmas celebrations for children. Those events also generated money, because foreigners liked to attend them. They really fancied the way Russians were able to rejoice," said Marina Sigirji.

By the way, it was the Russians who helped local residents discover such fun as visiting the beach. As the author of the book said, before Russians arrived to Turkey, the concepts of “beach” and “beach vacation” had not existed. But Russians could not do without water in such a hot climate and began to arrange beaches. And local magazines began to publish cartoons: a Turk is sleeping and dreaming of half-naked women on the beach.

Russian “strangers”

Of course, Marina Sigirji could learn all these details only from descendants of the emigrants. But making contact was not that simple - they turned out to be very reserved people. And it can be understood: not only did they lose their homeland, but also remained “strangers” in Turkey – that was how they were called there.

But still, Marina Sigirji managed to get into conversation with those few descendants of white émigrés who has survived to this day. She learned a lot of interesting information from Elena Gordienko, the ballet school founder. She was confided with memories of Roksana Umarova, as well as Larisa Timchenko - a granddaughter of the famous Sochi shipowner and a daughter of a white officer, and Vera Gilbert - no less than the granddaughter of Vera Kholodnaya, the first star of silent cinema. As the author of the book notes, they all spoke excellent Russian. And at the same time every one of them speaks several foreign languages.

Presentation by Marina. Sigirji

It is kind of amazing that while conducting the study, the author was able to find names of Russian emigrants, who their relatives in Russia did not know anythingabout. And thus she even managed to unite some families. Such as, for instance, the family of Dr. Krasovsky’ descendants. He was an honorary citizen of Yekaterinburg. One of his youngest sons stayed in Russia and became a mathematician. And his eldest son immigrated to Constantinople. Relatives in Yekaterinburg learned about the book being prepared for publication from the media and contacted Marina Sigirji. She helped them get in touch with relatives in Istanbul. So this family reunited a hundred years later.

New publications

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.  Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.

Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.  When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.  Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."

Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."  "Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...

"Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...