Russian village in Potsdam: Monument of Friendship between the Prussian King and the Russian Emperor

/ Главная / Russkiy Mir Foundation / Publications / Russian village in Potsdam: Monument of Friendship between the Prussian King and the Russian EmperorRussian village in Potsdam: Monument of Friendship between the Prussian King and the Russian Emperor

Svetlana Smetanina

The Russian village of Aleksandrovka, an amazing corner of Russian history, has been preserved in one of the districts of Potsdam. The Alexander Nevsky Memorial Church, the oldest surviving Orthodox church in Germany, is located on a mountain nearby. The history behind this village is, first of all, the story of friendship between two royal persons - Frederick William III of Prussia and Alexander I of Russia. Andrei Chernodarov, a historian and cultural expert, told the Russkiy Mir on how this unusual monument came to existence and how it has been preserved.

– How did this story appear in your life? How did it spark your interest?

– Back in the middle of 1990s, when I came to Potsdam for the first time, I saw houses that looked just like Russian ones. I walked around the area and became interested in its history. And then, a few years later, there came the opportunity to take part in one private project - I was the director of the Aleksandrovka Museum (we call it AleksandrOvka - that’s the way it is stressed here). And at that time I was very focused on the history of this village and, in general, the history of Prussian-Russian relations at the beginning of the 19th century. And in 2013 I organized a large exhibition in Berlin. It was dedicated to the joint Russian-Prussian campaign against Napoleon. The logical pinnacle event of that glorious page in relations between Russia and Prussia was construction of the monument of friendship and joint victory, namely - the village of Aleksandrovka, by decree of William III of Prussia in 1826.

Aleksandrovka. Russian soldiers in the Prussian army

– And who became the first inhabitants of this village?

– It has to be noted that there are some misleading legends where the story of Aleksandrovka is confused with the "big soldiers" of Peter the Great, whom he had presented to the Prussian king about a hundred years before our memorial village appeared. Aleksandrovka was built as a monument to the joint victory over Napoleon, since it had been achieved by the united Russian-Prussian army under a single command. When December 1825, Alexander I suddenly died, William III took it as a personal tragedy. Prussia declared three-day nationwide mourning. Close courtiers were afraid that the king would become depressed and that it would be impossible to communicate with him for several weeks or maybe even months.

But it did not happen, because William had come up with a great idea to build an unusual monument. And the idea itself was inspired by a trip to Russia in 1818 after marriage of his eldest daughter to Nicholas I, the future Emperor. At that time there was the settlement of Glazovo designed by Carlo Rossi near Pavlovsk, not far from St. Petersburg. It was built on the back of a rising tide of interest to national architecture after the victory over Napoleon and the liberation of Europe. Rossi studied Russian architecture and designed several typical log hut. Unfortunately, later that settlement was destroyed. But if now you are approaching St. Petersburg from the north, then you can see an unusual road in the Pavlovsk area which goes in a circumferential direction as if it was drawn by compass. This is the very place where Glazovo was located.

William III brought Rossi’s drawings and designs with him to Potsdam. He associated construction of a Russian village with memories of his beloved wife Louise, who had also passed away very early. During her life the Prussian king’s family had many warm meetings with the Russian emperor. And Alexanderplatz was built in Berlin after one of such meetings in 1805.

Louise admired Alexander I to the great extent and half of Europe made jokes about it. There is a whole series of English cartoons about Louise getting fond of the Russian Tsar. Such statement, of course, has no any historical grounds. There is a letter from Louise to her husband in which she wrote that it was necessary to maintain friendly relations with such a clever monarch as the Russian emperor.

So, William III mourned two close people at once. The challenging task of building a Russian village was assigned to Peter Joseph Lenné, the royal gardener. But in fact, he used to build villas, palaces, and designed parks. He was a man of numerous talents, who made a huge contribution into development of Prussian culture in the 19th century. He had previous experience in constructing a Russian log hut, which had been built when William III decided to surprise his daughter and Russian son in law during their visit. Now this place in Berlin is called Nikolskoe - in honor of Nicholas I.

Back then technology of building log huts was not known in Prussia. Although there were wooden settlements of Lusatians, a nearly extinct Slavic nation, in Saxony, Eastern Germany. They used to build log houses, but since Saxony and Prussia were on hostile terms, such type of construction was completely unknown in Prussia.

So, in 1819 a hut to surprise was built in a very beautiful place on the banks of the Havel River. It was a hunting area. William III came up with the idea that when his daughter and son-in-law got tired of hunting, he would bring them to the edge of the forest, and they would see a Russian hut there. Such a romantic man he was.

It was the first experience of building Russian log house for Peter Joseph Lenné. And for construction of the Russian village he was given military builders. They had to build 14 houses in a year. Aleksandrovka was located near a small mountain, which a tea house and a chapel were built on. The mountain is called Kapellenberg. Thus, the whole village could be observed from the mountain or from the balcony of the teahouse. Aleksandrovka had the form of a hippodrome, which was supposed to remind of military campaigns. And the St. Andrew's Cross, formed by shaping linden alleys, was inscribed in this hippodrome. The Prussian king also received the highest award of the Russian empire when he and Alexander had entered Paris in March 1813. Moreover, William III entered Paris in Russian uniform.

Photo 2. Aleksandrovka, top view

Nowadays, unfortunately, the village cannot be seen from the mountain because of forest that covered it in the 20th century. When I was the museum director, we had a good relationship with the mayor and got the idea to cut off a clearing so that the village could be seen from the teahouse. But local green-minded parliament members were against it.

In April 1827, the village was completed. But making 100% authentic Russian log huts did not work out. They used local technology, which assumed that wooden frames were filled with stones or clay mass - the so-called fachwerk houses, and only then logs sawn in half were put on the facade. When you enter Aleksandrovka, you get the full impression of being surrounded by Russian log huts. Moreover, the ornaments taken from Rossi’s drawings give the village authentic Russian look.

And when the village was completed, they remembered that there were Russian soldiers in the Prussian army…

– And how did they end up there?

– Actually, in 1805, Alexander I actively tried to convince Prussia to cease its military neutrality and form an alliance with Russia. But at that time he didn’t succeed. And after Napoleon occupied Berlin, William III and his family had to flee. When the decree of surrender was signed in 1806, Prussia pledged to fight on the side of France, and during the first clashes in Courland about five hundred Russian soldiers were captured.

Subsequently, the Prussian army switched to the side of Russia, and most of the prisoners returned to Russia, but not all. Actually, William III was really fond of Russian songs and even studied Russian. He especially liked when soldiers marched and sang Russian songs during campaigns. An unusual idea came to his mind - to organize a Russian choir for the Prussian army. For that purpose he selected 62 soldiers who could sing.

So when the village was completed, they remembered about those Russian singers. There were 13 of them left by that time. According to the king’s resolution, only married people could get a hut with the right of inheritance by their eldest son, but without private ownership. That is, all the smallest things in the houses - mugs, pans, furniture - belonged to the king. The whole village was the private property of the royal family, and the soldiers, who settled with their families in the memorial houses, received, kind of, a new home station, turning into peasants overnight.

Three types of houses were built in the village - for ordinary soldiers, non-commissioned officers, and also for the sergeant major, who supervised everyone. That is, it was like a continuation of military service for those people.

They had to maintain the garden. If you come to Aleksandrovka in May, you will feel the unusual smell of blossoming fruit trees. About 150 heirloom varieties of plums, apples, pears and even quinces have been preserved there.

– How long did the village exist?

– The houses are still there. But fate of the first settlers and their children was diverse and even tragic. They were all middle-aged people; their wives were not from Russia: some had met their wives in Paris, many had married in Prussia. Two years after construction of the village, one of the settlers died. Since he did not have a son among numerous children, his unfortunate widow and his daughters were simply evicted - she was given 50 thalers of resettlement benefits, and that was all. It was a very tragic fate.

But still, some descendants have managed to live in these houses up to our time. Currently Joachim Grigoriev, the only descendant of the first settlers, lives there, and he is truly the last one, because he has no children. It turns out that his ancestors lived in this house for 200 years.

Joachim Grigoriev next to his house

– And who lives in the rest of the houses?

– During the Second World War, when Soviet soldiers entered Germany, a commandant's office was located in this village. Because of that, the village was not bombed, and it was preserved. But when the Berlin Wall collapsed, after the reunification, Potsdam did not have any funds to save the village. During the GDR time, there were even plans to demolish it and build a hotel complex on its place. Fortunately, residents of Potsdam stepped in and stood up for Aleksandrovka. After the reunification, the then mayor came up with the idea to sell these houses to private owners. So it was done. Now it is a private property. But the complex itself, together with the orchard, is under UNESCO protection. The houses were restored and revived again. However, the restoration affected the houses differently – in some cases it was more successful, then in others.

Joachim Grigoriev lives in a house which he does not own legally. After the reunification the house was bought by a bank joint-stock company, which granted him the right to live in the house for life. His wife died last year, and now he lives alone.

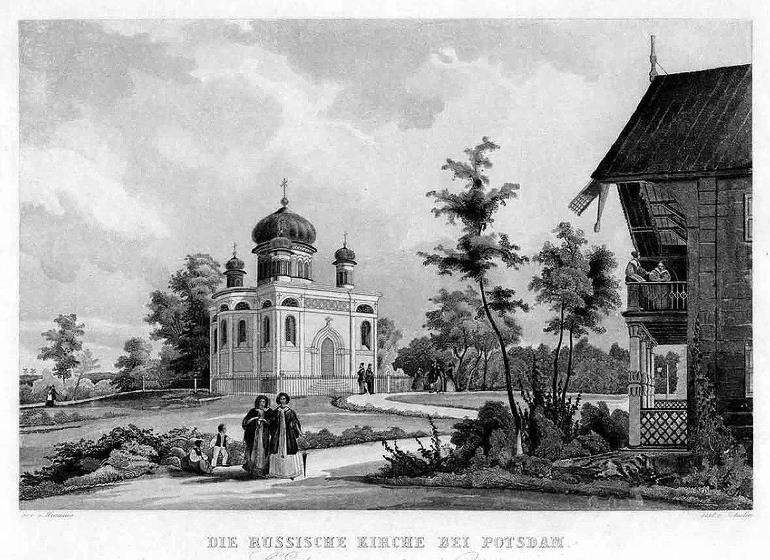

Russian church in Potsdam. Historical engraving.

Nowadays there are guided tours taking place in this complex; there is a functional church and a small part of the remaining museum, which we established in 2008-2009. You can come in a house and see how it has looked from the beginning. The city takes care of the garden - there is a special office. It is a cultural asset. Sunday services are regularly held on Sundays in the Alexander Nevsky Memorial Church on the mountain. Currently it is the oldest surviving Russian Orthodox Church in Germany. There were older churches, but they did not survive.

Today Aleksandrovka is a jewel of Potsdam, which has been aware of it more than ever. Tour routes run through the village; a lot of curious people come all the time.

Photos provided by Andrey Chernodarov

New publications

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.  Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.

Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.  When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.  Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."

Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."  "Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...

"Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...