There's Always a Need for People Who Read

/ Главная / Russkiy Mir Foundation / Publications / There's Always a Need for People Who ReadThere's Always a Need for People Who Read

Marina Bogdanova

The question, “What are you, illiterate?” has long been regarded as ironic. Indeed, some may be more capable than others, but everyone in Russia can read and write, so no one would ever think of patting themselves on the back for it. International Literacy Day is celebrated right between Knowledge Day (1 September) and World Teachers’ Day (5 October). Perhaps this is why this holiday isn’t very widely celebrated in Russia.

On 1 September all the children in Russia head off for their school desks. We have a holiday for Slavic writing, Russian Language Day (celebrated on Pushkin’s birthday), and a separate Book Day. It would seem that we don’t need a separate Literacy Day. And nonetheless, this is a good and needed holiday.

In 1965, the World Conference of Ministers of Education on the Eradication of Illiteracy was held in Teheran, UNESCO declared the date this conference began, 8 September, a new holiday from 1966 on: International Literacy Day.

Of course, the concept of literacy today extends well beyond the bounds of simply knowing the alphabet. Literacy in 2017 involves the ability to orient oneself in the world of advanced technology, a strong foundation sufficient for acquiring new types of knowledge, and open access to education, regardless of differences in material circumstances, gender, or anything else. In fact, UNESCO designated this year’s theme as “Literacy in the Digital Age.”

Nonetheless, there are more than 700 million adults on the planet who are illiterate in the most literal sense of the word. Two-thirds of them are women. Many children cannot attend school, and the UN is fighting this problem by raising the awareness of people all over the world, financing educational projects, and rewarding those who help spread literacy worldwide.

So what has been the state of literacy in Russia?

Do you know how to read?

Before the Revolution, no one was surprised by the question, “Do you know how to read?” And people frequently anwered in the negative. Meanwhile, even some of those who answered affirmatively would seem totally unschooled by today’s standards, as they could really only sign their names. It was often the case that a person could read only by sounding out the words and couldn’t write at all. Such people were called “semi-literate.”

It’s certainly difficult to state categorically what the state of literacy was in Ancient Rus. One the one hand, the large number of birch-bark letters found in Novgorod during excavations testifies that the people of Novgorod thoroughly availed themselves of the written word. They sent each other requests, instructions for household management, and confessions of love (evidently, it was easier to trust birch bark than to speak about one’s feelings).

Incidentally, one of these birch-bark letters is written by a young woman scolding her absent lover (letter No. 752): “I’ve sent you three letters. What spite have you for me that you do not come to me? And I regarded you as a brother! Now I see that this isn’t pleasing to you. If it were pleasing to you, you would have torn yourself from the public eye and come. Perhaps I injured you by my own misunderstanding, but if you should begin to mock me, may God judge you, and I, who am unworthy.”

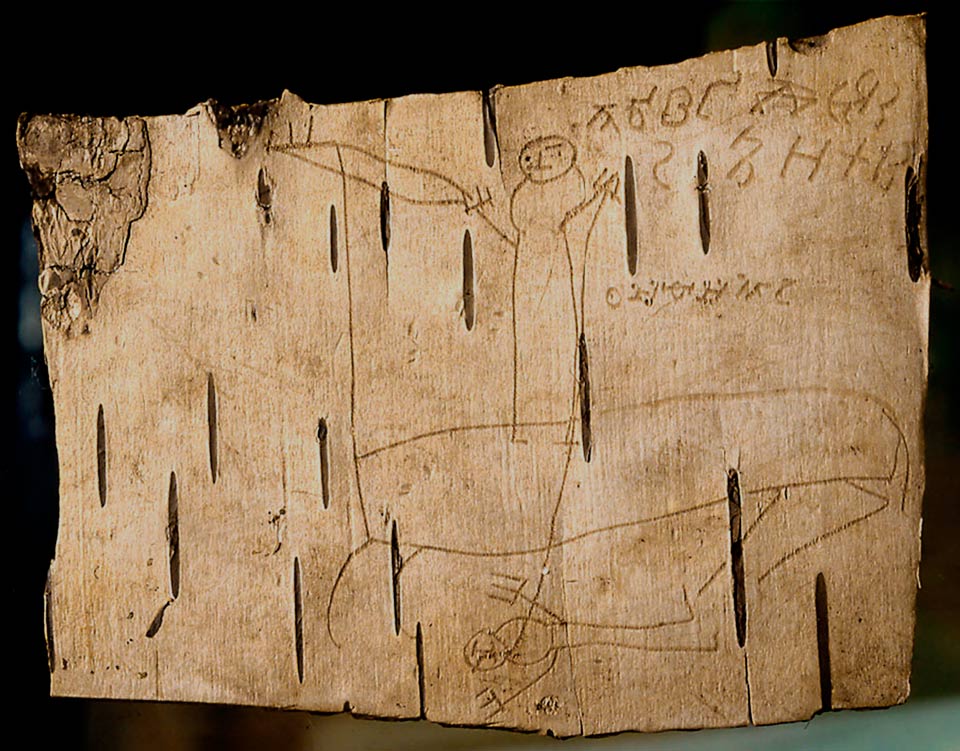

Great Novgorod conducted far-reaching trade with Europe. In this free city of merchants and tradespeople, the men, women, and children were all literate. The six-year-old boy Onfim—whose name we know because he signed his letters—has become a real archaeological “star.” The simple drawings he scraped into birch now decorate the covers of serious scholarly works. Onfim and his friend Danila entertained themselves, drawing on birch bark—maybe even during their classes, just like schoolchildren of our era.

[Birch-bark letter by Onfim]

Of course, Novgorod wasn’t the only city where people learned to write and exchanged letters. Birch-bark letters have been found in Vologda, Pskov, Ryazan, and Smolensk. It’s just that the marshy ground of Novgorod preserved the fragile birch bark, which made it possible for scholars to find “notes” dating back almost to the 12th century. What’s more, scholars know for certain that there existed schools organized by the princes (who needed literate priests and managers).

Unfortunately, wars, political disorder, and raids by conquering forces have decimated our national culture. Fires consumed the libraries and schools, and educated people either perished or were enslaved. Alas, just like today, wherever there’s war, hardly anyone has the time or strength to study. As a result, in addition to the princes, boyars, and soldiers, even the clergy remained largely illiterate. Often even completely illiterate priests received the orders and conducted masses by memory—or however God directed them. (Gennady, the bishop of Novgorod, complained about this, saying that there was no one to “add to the priesthood” and no one to teach new priests.) Gennady begged Tsar Ivan the Great to found a school that would teach the alphabet and reading by the Psalms, but this didn’t bring any real benefit. When prospective members of the clergy were asked why they were barely literate, they would answer: “We learn from our fathers or our masters, and we don’t have anywhere else to study; they teach us all they know. Earlier, though, there were many schools in the Russian realm, in Moscow, Great Novgorod, and other cities. They taught how to read and write and sing. And so, back then, there was a lot more reading, writing, and singing, and there were singers, lectors, and good scribes, who were renowned all across the land and remain so today.”

Books and Bookmakers

At one time, when the “Judaizer” heresy broke out in Novgorod, the priests couldn’t do anything about it: they simply didn’t have enough expertise to argue with the learned heretics, who, unlike them, knew how to read, knew foreign languages, and could augment their words with specific biblical quotes. Education always distinguishes the bogatyr hero in Russian folk tales as an especially rare virtue; he is always distinguished by his education—he “lays on the cross as it is written, makes bows as it taught.”

The famous library of Ivan the Terrible—the wealth of which astounded the select few who were allowed to see and appreciate it—was left lying as a dead weight in the closed chambers of the Kremlin, since later Moscow rulers couldn’t read it. These books in Latin, Greek, and Hebrew (numbering more than 800) had at one time been brought from the East. For a long time, they were kept under lock and key, and then they disappeared entirely, becoming one of the many legends of Moscow.

Of course, monastery libraries were used with much more care, but even the common clergy didn’t have access to them, much less the laypeople.

In the presence of Ivan the Terrible, the Stoglavy Synod decided that priests and sextons should teach their children at home how to read, write, sing church music, and recite from the lectern. Unfortunately, this promising initiative wasn’t sufficiently developed. What’s more, the manuscript books required for teaching how to read contained such a great number of errors, misprints, and incorrect interpretations that printing pioneer Ivan Fyodorov would attest: “Few suitable books were found among them. The rest were spoiled by scribes who were ignorant and benighted in the sciences, and some things were ruined by the carelessness of the writers.”

Ivan the Terrible spared no expense in his attempt to found a printing house in Moscow. And finally, true enthusiasts of print appeared among the Russian people: Ivan Fyodorov and his assistant Pyotr Mstislavets. A printing press was brought in from Poland and they released their first books, The Apostle and the Book of Hours. But despite the generous financial support coming directly from Ivan the Terrible, and despite the success of the enterprise and its support at the highest level, everything ended in sorrow—as the Russian saying goes, “sometimes the tsar’s benevolence isn’t shared by his servants.” The English diplomat and memoirist Giles Fletcher wrote that the typography was set on fire one night. The press and its expensive instruments burned to the ground, and it was a miracle that the workers survived. Fletcher suggested that this was orchestrated by the ignorant clergy who feared “that their own ignorance and ignobility would be exposed.” Fletcher was not a direct witness: he came only half-a-century later and described what had happened from secondhand accounts. It’s known for certain that Ivan Fyodorov and his associates were indeed forced to leave their home country, taking along with them a real treasure: engraved metal plates and printing type (obviously preserved from the fire). Whatever the true story was, the further activities of the first Russian book publisher continued in Europe.

Boris Godunov sincerely intended to change the situation and found secular schools, but fate is obviously not kind to politicians named Boris in Russia. Poor harvests, the ruler’s death, and the subsequent Time of Troubles all canceled out his labors. Although educational institutions gradually started appearing in the major cities (for example, the Greek and Hellenist Academy of the Likhudov brothers, which later became the renowned Slavic, Greek, and Latin Academy), literacy still remained the province of the very few who were fortunate enough to be born to the right kind of the family and in the right place—or who needed an education to get by.

Incidentally, literacy was a necessity for certain sectors of society, and these parents made sure their offspring were educated. In this category were the Old Believers, who couldn’t imagine themselves without a strict adherence to their canons and preserved “undefiled” holy books (without emendations). The exiled and persecuted priests of this old order sent numerous epistles to their spiritual children, and these instructions were piously preserved, read, copied, and hidden from outside eyes. Of course, it would be difficult for stern seafarers and those dwelling on the northern coasts to get by without reading. They would have had to have at least a minimal knowledge to read maps and the notes that accompanied them. As we will remember, the young Mikhail Lomonosov lived in the remote village of Kholmogory and had access to the leading textbooks of his time—the Grammar of Meletius Smotritsky, Arithmetic of L.F. Magnitsky, and the Psalms in Verse by Simeon Polotsky—because a local vicar had the full set, which became the “gates to learning” for the first Russian academic. And this was when there wasn’t even any talk of 100,000-book print runs or sending textbooks to every remote corner of the country.

Playing with Toy Soldiers

Peter the Great may have been the first to recognize the necessity of a broad primary education for his subjects. If wealthy and respected families sent their offspring to study abroad in order to make them educated specialists in the shortest possible time, special arithmetic schools were put in place for youths from middling noble families. The first such school was opened in 1701 at the Navigation school in Moscow. They taught children between the ages of 10 and 15 geometry, arithmetic, reading, and, of course, morality and etiquette. A second similar experimental school was opened in Voronezh, where Peter at the time expected to build the Russian navy. The navy idea didn’t pan out, leaving a significant hole in the budget, but in the end the tsar liked the arithmetic school—and from 1714 on, he ordered pontifical homes and monasteries to establish similar places of education.

It seemed everything was going great. A little while later there were two state-run schools in just about every city: a religious school and an arithmetic one to prepare soldiers, manufacturers, sailors—anyone the government might need.

The problems began when it came to realizing the plan. Instructors insisted on iron discipline and used draconian methods to instill it. It was often far from evident what benefit was gained from their lessons—and more importantly, many parents didn’t see any. In the end, merchants and traders gathered to make a petition to the tsar, pleading for him to free their children from schooling. Their motivation was quite simple: any merchant could teach this trade to their children from an early age, explain all its subtleties along with grammar and arithmetic, having the children train in their own shop or on trips far across the country (which brought greater benefit to the tsar). But instead, their children were wasting the most advantageous years for learning their craft in schools where they were only getting beaten and learning God knows what nonsense. Where would the next generation of merchants come from if their young people were wasting their time with such an education? And if there were no trade, there would be no tax money to maintain the army or build ships…

Peter thought about it and agreed to allow merchant children to study at home. Of course, the children of priests were sent to diocesan religious schools. So, there were hardly any students left for the arithmetic schools. The people didn’t appreciate the proposed idea of a state-sponsored basic education—and conversely, it was realized in a frightening and senseless way.

A network of garrison schools was opened for the children of soldiers. Here, boys of seven years and older studied reading, arithmetic, and military exercises. Afterwards, those who showed strong abilities would study further to become scribes, junior officers, military musicians, and artillerymen, while the rest would be either assigned to military service or appointed a trade. Tanners, smiths, and carpenters were in great demand in the army. The state gave these wards a minimum of food, clothing, books, and everything needed for their education. Every three years they were given a sheepskin coat, hat, and pants, and from the moment of their enrollment they received a small salary.

[Cantonist, 1892. Kharkov Art Museum]

Some time later, the garrison schools were restructured as cantonist schools, where soldiers’ children gathered along with young recruits including Jews (Jewish boys were allowed to be conscripted starting at age 12, in a proportion of 7 for every 1000 men, and very often parents would tearfully give up their young sons, who had barely undergone Giyur, in order to save their elders from service to the tsar), Gypsies, the children of rebellious Poles, and orphan children. Children from non-Christian faiths were deliberately removed as far as possible from their places of birth, and every effort was made to convert them to Orthodoxy. They would receive certain benefits for doing so, including a large monetary award, while stubbornness could cost a young man greatly. Cantonist military schools supplied the army with scribes, auditors, inspectors, cartographers, and also military musicians, that is to say, things were not so bad really. But the life of the cantonists was so joyless that for the rest of their lives many recruits wouldn’t forgive their parents, who had essentially sent them into a penal servitude they couldn’t escape: the term of service lasted 25 years, and the years of school drilling didn’t count. The young cantonists came into the service as strong, healthy lads but melted like wax from the intense drilling, poor nourishment, lack of medical treatment, and despotism of the leadership. The mortality rate in the cantonist schools was very high. Under Alexander II, as a sign of special monarchal mercy during the coronation, these schools were converted into normal schools for the military department, and all children studying there were allowed to return to their families if they wanted (and if there was still someone at home to return to).

Such was the situation of soldiers, who received an education by undergoing terrible suffering and often against their own will. And what about the peasants?

“Books Lay in the Box”

We are accustomed to thinking that hardly any of the peasants were literate, that this “dull and ignorant” mob had nothing to do with book learning. But in reality, this wasn’t the case. There is no doubt that there were literate peasants in the 18th century: historians have a large number of documents written and signed by peasants (petitions, “fairy tales,” interrogation reports). Incidentally, some added: “I know how to read but I can’t write cursive and didn’t study it.” Catherine the Great planned a total education for the male villagers in Russia, but (alas) there was categorically not enough money, teachers, or textbooks to make this plan a reality. The idea of popular schools was realized slowly and inadequately. (In all of Russia, there were only 40 schools, boarding houses, and village schools in 1786, with 136 instructors and 4398 students.)

The state of schools for the masses didn’t improve in the first third of the 19th century. Although the newly reconstituted Ministry of National Education worked out an excellent plan for ensuring a basic education for the common people, it existed only on paper. The responsibility for teaching enserfed children and keeping up the schools was placed on the landowners—and many of them did eagerly set up schools on their estates, follow after the children’s achievements, reward distinguished students, and send the most talented students to study further (recognizing that they themselves would also benefit from this).

But far from all the landowners shared the point of view that serfs needed education. The peasantry was officially barred access to the state schools of higher education (Mikhail Lomonosov had to pretend to be the son of a noble to enroll in the Academy), but there remained a range of opportunities for those who had personal initiative. Local clergy would teach children to read and write for a certain sum; what’s more, there existed the so-called “free teachers,” whose main trade was teaching peasant children. Sometimes, these would be retired soldiers, wandering monks, seminarians, and clergy members without a permanent position. Well-off peasants could pool funds to invite such “wandering” teachers (that is, teachers not assigned to any particular land) to their village and together set up a “free school,” providing room and board for the instructor.

On the first market day after the beginning of classes, parents bought their students alphabet primers and pointers. Studies would begin after a group prayer. To start, they studied the Church Slavonic alphabet and recited the possible combinations of consonants and vowels. Then, they moved on to reading the Book of Hours, canon calendar, and psalms. Next, they moved on to the civic alphabet, and then they acquired new textbooks. The transition from one educational book to another was a holiday for the teacher, the students, and the parents.

As a rule, children learned to read in the Church and civil writing systems in two winters. Study usually began in the villages on 1 December, when the peasants’ work was ended. On that day, they celebrated the memory of the prophet Naum and the future students prayed to the prophet for success in their studies. Of course, the books that peasants used were mainly manuscripts that were useful for working the land: “religious” books (with strictures), medicine books (with remedies for all diseases), songbooks, and so forth. Russian villagers very much loved reading and hearing “about the divine.” “Lubki” were also very popular. These were printed and crudely painted pictures accompanied by text.

Much later, when book publishing had already developed completely, special books—the cheapest and simplest ones—were released for peasants. However strange it may seem, the Russian books that have now become classics were not popular among the peasantry. The poet Nekrasov, who described peasant life quite accurately, enumerated the books that wandering book hawkers bought from a merchant wholesale:

They moved Blücher by the hundred,

As well as Archimandrite Photius,

And Sipko the bandit.

They sold out of The Jester Balakirev

And the English Milord.

What did literate peasants read in the 19th century? These very same books: the teachings of Archimandrite Photios, The Military Glory and Anecdotes of Blücher, a Prussian Field Marshall General and Knight Honored in Various States (although Nekrasov was more likely talking about portraits of the brave general—with his medals and aquiline stare), a lubok print of Matvei Komarov’s A Story of the Adventures of the English Milord George and the Margravine of Brandenburg Frederica Luisa, as well as the collection of jokes by the jester Balakirev and accounts of the lives of the bandit Vanka Cain and the conman Sipko, who impersonated military officers and noblemen. In truth, we can find an assortment in this very same spirit at any bookseller’s kiosk.

When they had learned to read and gained the opportunity to buy cheap books, peasants chose above all else to read literature with engaging adventure plots and fiery passions. Russian literature—with its psychology, deep attention to a character’s inner world, and extended descriptions of landscapes—wasn’t at all in demand among this demographic, although individual works by Pushkin, Karamzin, and Gogol were popular, as were the novels of Mayne Reid and…John Milton’s Paradise Lost and Paradise Regained. After all, this book was about the “divine” and about feelings.

Villagers also respected the press: they subscribed to newspapers and sometimes the illustrated journals Grainfield and Motherland. They often practiced “communal reading,” where everyone in a given village would gather in the evening, and those who were literate (sometimes including young students) would read a selected book to the assembly. Vasilii Vakhterov, the Russian pedagogue and enlightener, wrote: “Everyone who has observed readings in the village and seen the heart palpitations with which the village readers follow the protagonist’s sufferings and the enthusiasm with which they meet his successes; anyone who has heard the sincere, unrestrained Homeric laughter of the village audience when the characters of a story end up in a comic situation; anyone who has seen the tears of the more impressionable listeners, accompanied by the sighs and exclamations of the others, when someone reenacts an especially sorrowful event; who has heard the peasants’ judgments about something that was read simply and to the point—this person will know that a talented and interesting book, accessible to the common people and read by a good reader, will lay an indelible trace on a simple person, entering his worldview and becoming a substantial factor in his spiritual life.”

“Our great, powerful, true and free [language]…”

Things only really got moving after the emancipation of the peasants. Alexander II’s reforms succeeded at what so many organizations before him had tried to do in vain. The zemstvo schools were more than just a hypothetical success. What’s more, in the second half of the century a large number of volunteers from the raznochintsy class came to the villages hoping to teach and enlighten children and adults. Thousands of enthusiastic and unknown young women became teachers, traveling out into the villages like missionaries going to far-off lands. In reality, they knew very little about the real common folk and were guided more by noble ideas and certain abstract theories.

The narodniki (or “popular enlighteners”) wanted to learn from the people, “connect with their roots,” and find a place for themselves in the world. But for the most part they were deeply disillusioned after coming into contact with real peasants. The peasants thwarted their political agitation, going to the police themselves to turn in these strange people who dressed like them and spread seditious speech. The teachers and doctors who had gone “to the people” as if performing a glorious act were mainly a headache for the local administrators. And the peasants weren’t especially eager to hand over their children to be educated. They were happy to avail themselves of free medical aid, but not everyone agreed to let their children miss work to read books. The zemstvo schools—however good or bad they may have been—were a better solution than all previous attempts by the government or the beautiful intentions of the “narodniki.”

In 1897 the first general census in the Russian Empire took place. This was a very major project, in which a great number of people took part. (One of its active organizers was Pyotr Petrovich Semyonov-Tyan-Shansky.) Among the list of questions answered by everyone living in the empire, question number 12 asked whether the respondent was literate. And if they could read, where did they study? According to the results of this census, we know for certain that the level of literacy in the European part of Russia was 21.1%. The rate was substantially higher among men than among women (29.3% and 13.1%, respectively). All across the Russian Empire, the rate was 19.78%. Naturally, in certain regions the literacy rate was very high, and in other it was very low, but the basic fact remains the same. They were very far from having the entire population be literate. What’s more, literacy among peasants depended very strongly on their property holdings and size of their land. Well-off peasants could think about such an important matter, but to the poorer peasants education remained a total waste of time. Alas, even when they learned to read, people forgot this skill very quickly if they didn’t have continuing practice.

80% of Drafted Recruits in 1916 Were Literate

Under Nikolai II, community education became one of the most pressing tasks. In early 1913, the general budget for national education in Russia reached a colossal number for that time: 1.5 billion rubles. In 1914, there were 50,000 zemstvo schools with 80,000 teachers and 3,000,000 students attending. In 1914, 12,627 public libraries had been founded in the districts. The Ministry of National Education reported in 1911 (not without pride): “Summing up the results of everything that’s been said, we should note that the national primary school—which until very recently got by primarily on the funding of local efforts but is now supported by large allotments from the treasuries—is developing in the central Great and Little Russian provinces at a sufficiently fast rate with due cooperation between the government and local organizations, and that we may consider the achievement of a generally accessible primarily education assured in the not too distant future.”

These were not mere words. Every district city in Russia had preparatory schools with a high level of instruction. 80% of draft recruits in 1916 were literate. A survey conducted in 1920 found that 86% of young people between ages 12 and 16 knew how to read and write—and they had learned this before the Revolution, not during the Civil War. Indeed, the teachers in the first years of Soviet rule were graduates of those same zemstvo schools and preparatory schools. They knew how to teach back then.

On the eve of the First World War, Russia had more than one hundred institutions of higher education with 150,000 students. Students from lower social classes (the raznochintsy, workers, peasants, and others) made up around 80% of the class at technical secondary schools, more than 50% at technical colleges, and more than 40% at universities. And these numbers kept growing. Unfortunately, after the revolution and the related cataclysms, the numbers fell catastrophically. In 1927, at the 15th Congress of the Communist Party, Nadezhda Krupskaya lamented that the literacy of those drafted in 1927 was significant less than the literacy of the 1917 draft—over the last ten years or so they had lost ground.

Alas, the liquidation of total illiteracy took place at the hands of those who had organized it. Among the “de-kulakized,” exiled, disenfranchised, repressed, and the executed “counterrevolutionaries” there were not only the inveterate enemies of the new order and ideological opponents, but also those who were for whatever reason not liked by the militant mediocrity that had finally swept into power. The country was thrown into shock, and the peasantry was put on the edge of destruction by orchestrated famines and food rationing—so that people were more concerned with survival than with education. Especially since accusations like, “oh, look at that hat,” or, “what, are you the most educated person here?” could be sufficient cause for a lynching on the spot. According to the 1937 census, 30% of women didn’t know how to spell or sign their names (such were the criteria of literacy on the census). On the whole, a fourth of the population aged 10 and over didn’t know how to read, although the country was declared to be fully literate. The data of this census were soon confiscated and destroyed. Its organizers were repressed, and the 1937 census went into the annals of history as a document banned on penalty of death. The country was not able to correct its catastrophically fallen level of literacy until the 1950s, after the Second World War.

Today, when we can no longer imagine that an adult in our country could be unable to read and write, it most likely seems to us that we have already turned this page in our history. Really, though, we shouldn’t forget that literacy isn’t so much a privilege as a measure. It represents the peaceful life of a population, a certain level of prosperity, respect for intellectual labor, a high level of development in the arts and learning, and respect for oneself, as well as for the integrity of one’s language. National literacy isn’t about getting a high or low score on a standardized exam, nor is it about a rating in a journal. Indeed, UNESCO reminds of this truth as they celebrate the 51st International Literacy Day.

New publications

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.  Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.

Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.  When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.  Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."

Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."  "Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...

"Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...