The Myth of the Potemkin Village

/ Главная / Russkiy Mir Foundation / Publications / The Myth of the Potemkin VillageThe Myth of the Potemkin Village

Even if you know nothing about the centuries of bad blood between England and the Netherlands, the dictionary can tell you about it: Dutch courage (drinking until you feel brave), Dutch widow (a prostitute), Dutch bargain (one made while drinking), Dutch feast (one where the host is the first to get drunk), Dutch defense (a decoy defense), double Dutch (balderdash), in Dutch (in a difficult situation), I’m a Dutchman if… (I’ll be damned if…). Even today, when the wars of old have disappeared from memory, you could refer to a frog as a “Dutch nightingale” in England, or a dissonant choir as a “Dutch concert,” and you’d be understood. At one time, these turns of speech arose from spite, but they are included in dictionaries even today, though they may be marked “obs.”

But the “Potemkin village” doesn’t require any such marking, as it flutters about on the web, in print, and over the airwaves. Even though it has already been proved long ago—and it was clear to intelligent people from the very beginning—that this is nothing more than a fabrication based on deep envy.

The dissemination of the “Potemkin Village” tale is the most successful negative “PR campaign” in history. This myth has kept going for over two hundred years and continues to injure the country it was created to damage. The most surprising thing is that it functions not only outside Russia, but also within.

“Let them crack jokes, but we’ll get to work”

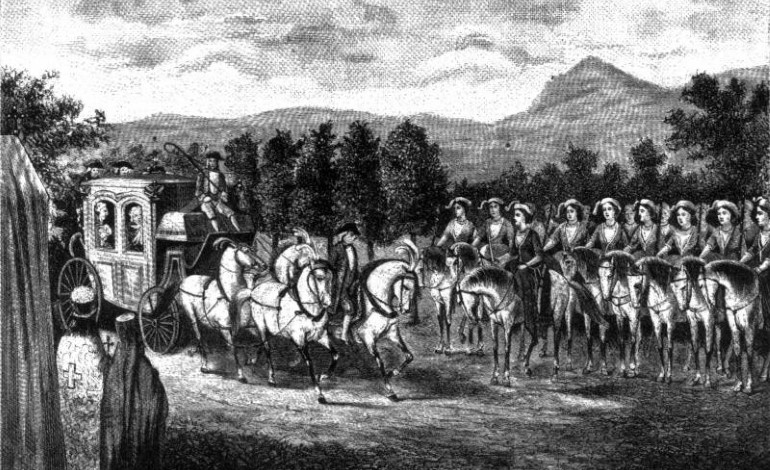

The late scholar A.M. Panchenko got to the bottom of this myth. In 1787 Catherine the Great showed her new lands, Novorossiya and the Crimea, to the Austrian Emperor Joseph and some foreign ambassadors. They sailed to the Black See from Kaniv along the Dnieper, docking overnight. Considering Austria’s misfortunes with Turkey and the sad state of Poland (Russia’s nearest neighbor to the west), the visitors were amazed by Russia’s accomplishments and the scale of construction in Ekaterinoslav (conceived as a “third capital” of the Russian Empire), Kherson, Nikolayev, and Sevastopol. They were especially struck by the shipyards, which launched their first ships in the presence of these visitors. Ekaterina did not escape the annoyance of some participants in this trip. She wrote to Potemkin: “I look upon the envy of Europe very calmly. Let them crack jokes, but we’ll get to work.”

Potemkin, who took the lead in transforming Novorossiya and the Crimea, was envied and opposed by many in Petersburg. Beginning in the 1770s they spread rumors that all of Potemkin’s reports on his activities in the south were a con. Anyone who arrived from there was subjected to biased questioning about the Black Sea fleet and the construction of cities and fortifications. They were expected to confirm that it was all a fantasy. Some people would answer evasively so as not to disappoint their questioners, and this would reinforce the rumors.

When the participants in the Empress’s “Crimean expedition” returned to the capital, Potemkin’s enemies sprung questions on them: Is it really true that there’s really no such thing as Kherson or Sevastopol? No ships or fortresses? They were disappointed, and the rumors started to quiet down.

Potemkinische Dorf

Twenty-two years later, Georg Adolf von Helbig a former representative of Saxony at the Russian court who didn’t even take part on the excursion, suddenly had an idea (under the influence of political circumstances). In 1809 he published the book Potemkin, Prince of Tauris, which claimed that the settlements along the Dnieper were stage sets, which were transported by night to be erected in a new place while livestock were also herded there. He went so far as to claim that someone traveling with the Empress had recognized some cows “by face.” Such transportation of livestock, people, and stage sets would be technically impossible even today, 230 years later, but the enlightened public are not aware of such things. Helbig also thought up the expression Potemkinische Dorf: “Potemkin Village.”

Strictly speaking, the hypothesis that there were false towns in the last years of Catherine the Great’s rule entered the head of another foreigner, the Frenchman de Piles. He either heard from someone or deduced himself that the settlements along their path must certainly be decorations, and the peasants were not locals. He wrote just a few lines about this in the 1790s. These lines might have come into Helbig’s possession and given him additional inspiration, if he needed it.

It’s impossible to describe the excitement that took hold of Europe in the wake of Helbig’s book. What psychological compensation! The elites in countries cramped by their geography could tell themselves: all of Russia’s victories, gains, fortresses, shipyards, ships, all of Novorossiya—it’s all just painted on a canvas. Hurrah!

As Panchenko observes, not one of the travel journals of the participants on the excursion contains a single mention of anything like this. Only one of them later confirmed Helbig’s tall tales—the Swede Johan Albrecht Ehrenström, a well-known schemer, who stood more than once, Panchenko writes, “in the pillory and once almost lost his head on the scaffold.” As for Helbig, the following fact, among others, unmasks his lying: A few months before the book about Potemkin, he released another book, Russian Favorites (Russiche Günstlinge), with a chapter about Potemkin that doesn’t mention the fake villages or disguised peasants.

Two Hundred Years Later

A little more than two centuries have passed since Helbig, but here are some of today’s headlines from foreign articles about Russia: “The Politics of Potemkin Villages in Russia” (Christian Science Monitor), “Potemkin Nonproliferation” (National Review), “Economic Growth Potemkin-Style” (Welt am Sonntag), “Potemkin GDP” (The Wall Street Journal), “Potemkin Russia” (Le Monde), “Putin’s Potemkin Russia” (United Press International), “Free-Market Potemkin” (The Wall Street Journal), “Potemkin Compromise” (The Wall Street Journal), “Potemkin of the 21st Century” (Newsweek), and so forth.

The Canadian journalist Mark Chapman writes (incidentally, his article is titled “Where did I get my degree? At a Potemkin University in California” and describes hundreds of companies in the U.S. and England that sell false degrees from famous institutions): “I’m tired of the unbridled love these Russophobic ‘news’ sources have for the word ‘Potemkin,’ which they use as a definition for everything. My search engine gives six pages of mentions for the word ‘Potemkin,’ but only twice is it used in its proper meaning: the battleship Potemkin and the last name. But there are too many other links to count: ‘Potemkin villages,’ ‘Potemkin cities,’ ‘Potemkin monitors,’ ‘Potemkin abbreviations,’ ‘Potemkin presidents,’ ‘Potemkin congresses,’ ‘Potemkin prisons,’ ‘Potemkin projects.’ What are you doing, guys? Are you lazy or out of ideas?”

One is surprised not by the cliché, but by the strength of their passion. The liveliness of the “Potemkin” tale is a fact of Western, not Russian history. The West’s infatuation with Russia brings to mind a boy pulling on a girl’s ponytail so that she will pay attention to him, declare that he is the best there is, and fall in love.

As Max Hastings, a staff writer at The Guardian, complained (in the November 27, 2006 issue): “there is something of the bitterness of rejected courtship in our response to their [Russia’s] recent behaviour.” In light of this explanation, the phenomenon of the Western passion for the “Potemkin” label is more understandable.

That’s not the real question. Why do many of our own publicists continue to use this tale of the “Potemkin village”? It’s difficult to imagine intelligent Russian authors who, decades after Panchenko’s work appeared, still haven’t heard any indication that the Potemkin mythologeme is a malicious invention. Or are they not intelligent enough?

And to finish with the “Potemkin” issue: “In preparation for hosting the July 2013 G8 summit in Enniskillen, Northern Ireland, large photographs were put up in the windows of closed shops in the town so as to give the appearance of thriving businesses for visitors driving past them.”

Aleksandr Gorianin

New publications

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.  Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.

Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.  When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.  Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."

Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."  "Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...

"Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...