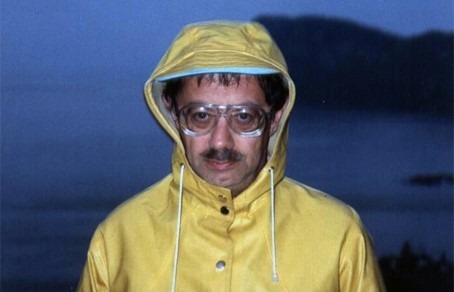

Our interview with New York writer, political expert and opinion journalist Vladimir Solovyov is the first conversation in a new series of dialogues with creative people living abroad. Vladimir Solovyov expatriated to the US with his wife Elena Klepikova in the 1970s, back when people didn't have a choice on whether to leave the Soviet Union or stay there. Since then, many books written by Vladimir Solovyov have gained popularity in the US and Russia. Some of them have been translated into 13 languages.

How did your expatriation to the United States go? Do you remember anything about that life-changing event?

How did your expatriation to the United States go? Do you remember anything about that life-changing event?

Of course I do! Our departure was abrupt and very quick. And even though we were registered as expatriates, we didn’t expatriate—they expatriated us. They offered us to leave the country at once, in three days; it wasn’t easy to persuade them to give us seven more. We chose the West, because they sent us a clear message: our only alternative was the East, meaning court, prison and exile.

I have a chapter entitled Solovyov-Klepikova-Press in my book Notes of a Scorpion. It was the name of the first and only independent information agency in the Soviet Union I co-created with my co-author Lena Klepikova, who is also my wife. We broadcast news internationally and heard our own messages later, retranslated via “enemies’ voices”.

Suffice to say that The New York Times regularly printed our messages and political commentary. Once they even published a front-page article about our agency, which made our life much easier when we came to the US. After receiving grants from the Columbia University and the Queens College at the City University of New York, we started writing for leading American newspapers, from The New York Times to The Wall Street Journal to The Washington Post to Chicago Tribune. Soon the United Feature Syndicate agency acquired the rights to our articles and we signed a contract to spread them. It’s not just that we held our own with local writers; we were once among the three nominated finalists of the Pulitzer Prize. Then, quantity gave way to quality: we published several political thrillers about Andropov, Gorbachev and Yeltsin for six-figure advances—first in English, then in other languages, and finally, in Russian during Glasnost.

Many are interested in your book Being Sergei Dovlatov. The Tragedy of a Cheerful Person. Sergei Dovlatov is a cult figure both to Russian-speaking readers and to Russian Americans. There is a reason a street in Queens was named after him. What is your take on this author?

Dovlatov is one of the tragicomic writers—comedy writers who lived a tragedy. Swift, Zoshchenko, Dovlatov. This is why we named our latest book about him Being Sergei Dovlatov. The Tragedy of a Cheerful Person. Unlike our previous book Dovlatov Upside Down, this one is aimed at defending him against the slander, envy and malice of his “frenemies” among writers.

I’m not talking about those who critique Dovlatov’s prose like Dmitry Bykov does—there’s nothing wrong with that, and I myself am not an unabashed fan of this writer. I consider many of his contemporaries superior, like Fazil Iskander, two Lyudmilas—Petrushevskaya and Ulitskaya—and three Vasilys—Aksyonov, Belov and Shukshin. Dovlatov is a perfectionist rather than a chef-d’oevre-ist.

But there’s a world of difference between critique and criticism. Some colleagues of Dovlatov from St. Petersburg have a tendency to reduce his prose to jokes or anecdotes, pitting oral discourse against the written one, insisting that Dovlatov was better at telling stories than writing them down, or saying that his letters contain his best writing, which is total nonsense...

Our book contains Sergei’s oral tales and letters, destroyed and later restored by ourselves virtually from the ashes. We also included a number of research-cum-investigations of mysterious events in Dovlatov’s life, from the love of his youth to his horrific death in an ambulance when two dumb paramedics tied him to the stretcher: according to the driver, Sergei “choked on his own vomit”. So he died because of this, not because of cirrhosis or a heart attack! I consider his death involuntary manslaughter.

You didn’t rest on your laurels and went on to make a documentary My Neighbor Seryozha Dovlatov. There have been many recollections of Dovlatov. How do you remember him?

In a variety of ways. Different. Witty, yes, but never cheerful. He had no reasons or occasions to be cheerful. He led a joyless life of a loser in Leningrad. He wasn’t merely an unpublished writer; even his peers didn’t consider him a writer. His only literary evening took place at the House of Writers in Leningrad, when I gave an opening speech and Sergei read his hilarious short stories to the public. It was only in New York when he came into his own as a writer. All of his books were published here, first in Russian, then in English and other languages. His articles were published in the most prestigious magazine, The New Yorker, and he worked as an editor for the Russian-language The New American newspaper. To him, emigration was a vita nuova, but not a dolce vita.

Do you know many like-minded people who stayed in the US? If you ever think of borders, that is?

How can writers ever be like-minded? Even Elena Klepikova and I are different-minded! Do you know where everyone thinks alike? In the graveyard. I’d rather call those people “together-minded”, and I have those in spades around the world. Like chief editor of a Russian-language newspaper Natasha Shapiro who has been publishing Paradoxes by Vladimir Solovyov for a dozen of years, or editors of Moskovskij Komsomolets and Nezavisimaya Gazeta who printed many essays from our future books—the ones about Yevtushenko, Vysotsky, Brodsky, Dovlatov and Shukshin.

My generation spans people from Brodsky and Dovlatov to Baryshnikov and Shemyakin. A feast in time of plague, someone said. What do we have in common, regardless of individual differences? We were all born in the 40s, we hail from Leningrad, and now we’re New Yorkers—a polar opposite to the Sixtiers.

To what extent do you think a place of residence affects one’s creativity?

It depends. The surroundings may change, but strong emotions are the same everywhere. I am not an ethnographer; I’m an engineer of the human soul, to borrow a neat turn of phrase from comrade Stalin.

Is living in the US essential to your creative process?

Well, creative is a big word. Working. No matter where. Like in a jar—remember Diogenes? Anton Chekhov wrote on a windowsill, Ilya Erenburg did the same in cafes. The only thing you need is something to write with and something to write on. Freedom? I am free when I write, no matter where my desk is.

What is your vision of the Russian World? Do you feel its presence in the US, now that the migration flow has greatly diminished?

What makes you say that the migration flow has diminished? Look at the latest numbers released by the Department of State: 265,000 Russians have applied for a US green card this year, and we have two months to go. There will be one-third of a million people, like the number of Syrian refugees in Europe! Do you know how many Russians with a different status live here—diplomats, guests, students? Well, not just here—there are many Russian-speaking people around the world. When I was in my beloved Sicily for a third time, I noticed the number of our people had grown again; you hear Russian speech wherever you go. Even more so in the US. Wherever you go in New York City—cinemas, theaters, exhibitions, fancy restaurants—you’d better not discuss intimate topics: someone will hear you and understand everything!

When we released the first book in our Dovlatov series, we were extremely popular: sold-out nights in New York libraries, Long Island literary club, Silicon Valley in California with $30 admission and another $30 for a signed book! The audiences were wonderful—grateful, appreciative and intelligent. One of my publishers in Moscow used to say he sold more books abroad—in the former Soviet Union and beyond—than in Russia.

The world of the modern Russian culture is polycentric, there is no metropolitan state, nor even a capital. I will hear nothing to the contrary. To paraphrase medieval philosopher Nicholas of Cusa, the Russian World is everywhere and its center is nowhere.

How did your expatriation to the United States go? Do you remember anything about that life-changing event?

How did your expatriation to the United States go? Do you remember anything about that life-changing event?