The First Russian Librarian

/ Главная / Russkiy Mir Foundation / Publications / The First Russian LibrarianThe First Russian Librarian

Today the name of Schumacher (from the German “shoe maker”) has been entirely monopolised in the public imagination by the famous Formula-1 racer. Yet in Russian history the name belongs, first and foremost, to a certain Johann Daniel Schumacher. This German intellectual played a major role in bringing Western education to Russia as the country’s first librarian. He is also known for his conflict with a famous contemporary, the Moscow-university-founder and “all-Russian man” Mikhail Vasilevich Lomonosov. On 5 September Russia celebrated the 325th anniversary of his birth.

Forget the strict old ladies that run our libraries today; in ancient times the profession of librarian was considered to be an exclusively male domain. The book-keepers in the Great Library of Alexandria were always men, and men, moreover, of the greatest intellectual stamp. Of course the revered status of librarians reflected the rarity, expense and prestige of written material in the pre-printing era. At this time, all those who were connected with the care of this material were sanctified like members of a religious order. It is not surprise, then, that for thousands of years librarians were drawn from the priesthood. Russia was not an exception to this rule.

Exclusively a Man’s Job

Until 1917, women were forbidden from serving in Russian state libraries. Those wishing to serve in the Imperial Public Library, at the time the largest in Russia, were required not only to possess an outstanding education, but, as a minimum, to read Russian, French, German, Latin and Greek. Even junior staff at the library were required to speak a minimum of three foreign languages, and to rise to the top of the ranks in the administration was more difficult at the library than it was in the country’s universities.

The story of the library began with Daniel Schumacher. He was born in 1690 in the small town of Colmar in Alsace. Alsace, on the border between France and Germany, has exchanged hands many times, and has long had a mixed population. Schumacher was born into a German family, and grew to be German from head to toe, with all the virtues and flaws we associate with the scions of that great European culture. Thus did Schumacher begin his literary career in the typical German way by writing poetry as a youth.

A New Kind of Library

After graduating from the Strasburg University, where he studied philosophy, Schumacher did not hang around in his native Alsace for long. Already at the age of 24 Schumacher accepted an invitation to come to Russia. This was the era of Peter the Great, when Russia was first embracing Western progress, and in the backwards Russia of the time, Schumacher, despite having only a passing acquaintance with the practice, was immediately installed as a high-ranking secretary in the department of medicine. As for his poetry, the ever-practical Peter, alas, had little time for it.

The great reforming Tsar was, however, an ardent collector of books, and by the end of his reign the imperial library had grown to such proportions that it was, say contemporary researchers, to become one of the lynch-pins around which Russia’s world famous Academy of Sciences was to form. The time was already ripe to bring some order to this chaos, and make a modern library out of the thousands of books, many unique, which Peter had had brought over from Europe. It was Schumacher who was chosen for this task.

The Tsar spared no expense for the new library. In 1721, Schumacher was sent back to Europe, charged not only with acquiring new books for the collection, but also with studying the latest library-keeping techniques in the leading literary repositories of Europe. On his return, Schumacher presented Peter with copies of library catalogues from institutions as far afield as Cambridge University and the Vatican, as well as with a comprehensive account of what he found during his journey and the conclusions he had drawn. Today this account is considered to be the foundational text of Russian secular library-keeping.

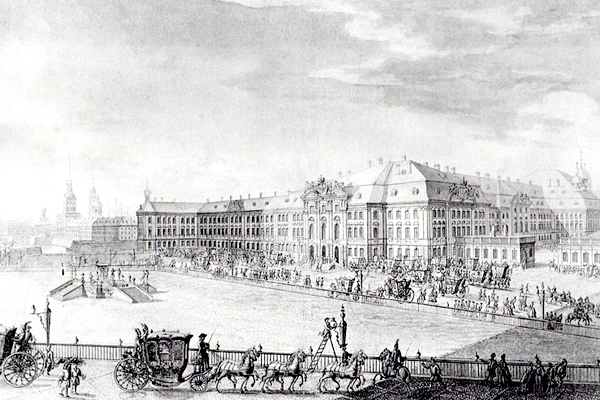

Schumacher, in fine Petrine form, embodied the reforming spirit of the age. Just as Peter the Great created a new army designed along Western standards, Schumacher created a new library that bore little resemblance to the dark, dusty monasterial book repositories that had represented the sole achievements of literary collection in pre-Petrine Russia. The new library was public, had a full and varied fund of scientific books, a systematic lay-out, a detailed catalogue that was soon being published in four volumes, and comfortable reading rooms.

“Chief Commander to the President”

Johann Schumacher had another mission on his European travels; the Tsar urged him to attract to his services the best academics and scientists from across Europe. In this role, Schumacher, long an excellent persuader, enjoyed considerable success, though his efforts were certainly made easier by the solid sums from the Tsar’s treasury that were laid at his disposal. The Tsar soon boasted some of the greatest thinkers of the age in his service, such as the mathematicians Daniel Bernoulli and Leonhard Euler, as well as a whole host of young intellectuals setting out on their careers.

In 1724, the year before Peter’s death, the Russian Academy of Sciences opened, and Schumacher was installed as its head librarian. His official title, in modern English, would sound something like “Chief Commander to the President”, i.e. vice president of the Academy. With an annual salary of 1200 roubles a year, Schumacher earned more (at least officially) then many of the country’s regional governors.

Schumacher turned out to be an exceptional organiser, a capable businessman and, most importantly, a prudent pragmatist, who understood better than most that words butter no parsnips. Desiring that the library should supplement its income from the state budget, Schumacher set about establishing additional businesses, setting up a printing press, a bookbinders, and stone-cutting and engraving workshops. Our knowledge of how St Petersburg looked in these years comes, in no small part, from the images of the city engraved and printed by Mikhail Makhaev in Schumacher’s workshops.

Two Dogs over One Bone

In his later years, Schumacher became a target for the ire of an up-and-coming Russian intellectual who is now revered as Russia’s greatest genius of the 18th century and the man who popularise learning among Russians and perhaps did more than any other to lay the foundations for Russia’s later scientific achievements – Mikhail Lomonosov. As one famous Russian romantic writer once declared “Lomonosov is our everything!” The Russian cult of Lomonosov reached its height in the years following the Second World War, when the Soviet Union was at the peak of its scientific prowess. It was at this time that the Moscow State University was named in his honour, and moved to the famous building on Moscow’s Sparrow Hills where it remains to this day. With historians keen to downplay German contributions in this year, Schumacher was conveniently forgotten. His memory was, however, finally revised in the 1990s.

Although Schumacher could hardly boast of the kind of genius that Lomonosov possessed, he nonetheless made an outstanding contribution to the development of learning in Russia. It is true that, in accordance with the old adage “in Russia everyone steals”, Schumacher, making good his name, “shoehorned” funds out of the academy’s treasury. He was not like the famous example of his German compatriot, “Honest Sievers”, who as governor of Ekaterinburg was famed for sending every penny of the bribes that came his way into the city’s treasury. If ever there was an exception which proved the rule, his was surely it.

Schumacher also “shoehorned” his close friends and fellow Germans into several comfortable positions in the Academy of Sciences. It must, however, be said in his defence, that very few Russians at this time, whatever their origins, showed any genuine enthusiasm for the new learning. Lomonosov was to be the exception, the exception that, by way of his example and consistent campaigning, broke the rule. But in order to encourage his fellow countrymen into science, Lomonosov felt he had to break the German hold over learning in Russia. After all, the Russian and German characters are famously opposed to each other, while holding out a very strong attraction; the love-hate relationship of the Russian and German peoples has often been described as one of “cursed friends”. The most obvious target for Lomonosov, ever the Russian bear in both build and mentality, was Schumacher.

Lomonosov attacked by accusing Schumacher of embezzling funds earmarked for the Academy of Sciences. Of course Lomonosov himself was hardly a saint, and many are the memoir writers of the time who noted with disapproval his alcoholism and propensity for brawling with his famous bear-like paws. Thus the famous “case of the academics”, in which Schumacher was placed under arrest and eventually found guilty of stealing 109 roubles from the state treasury, was, argue many historians, the result of Lomonosov’s testimony.

Perhaps this conflict was inevitable; Schumacher and Lomonosov, both giants in their fields, viewed each other with mistrust and were unlikely to resist fighting over the same bone. We should, perhaps, respect the rule that it is best to focus on the good deeds of those long-dead rather than ungenerously fixating on the sins which, if we are being honest, we all share. Perhaps, then, it is best to give both men the benefit of the doubt. After all, whatever their faults, these men did more than any other to cultivate a respect for learning and knowledge which is, perhaps, the greatest attribute belonging to the modern Russian people. Let us never forget it!

New publications

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.  Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.

Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.  When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.  Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."

Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."  "Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...

"Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...