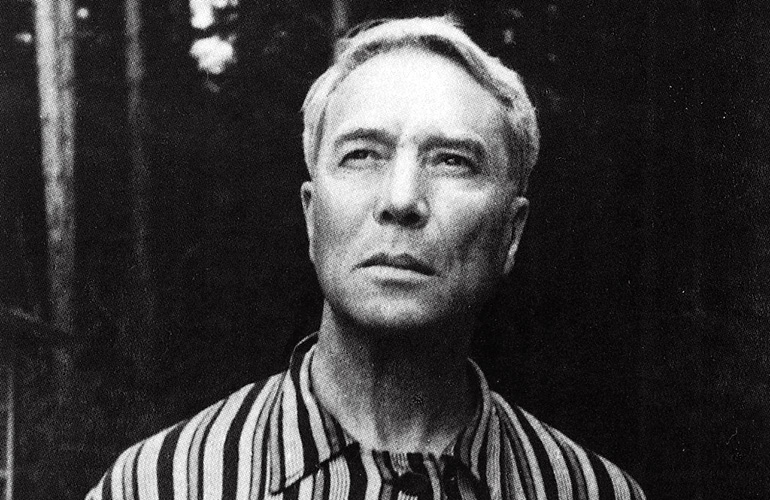

It sometimes seems that people in the world of arts live outside time. And it’s true that few are interested in the socio-political situation in the time of Dante, Goethe or Apuleius… But when you look back the people who just recently lived and walked along the very same streets that you do, their poetic metaphors suddenly find a place in the history of time. Boris Pasternak was one such poet who served as a chronicler of his time. February 10 marks the 125th anniversary of his birth.

It sometimes seems that people in the world of arts live outside time. And it’s true that few are interested in the socio-political situation in the time of Dante, Goethe or Apuleius… But when you look back the people who just recently lived and walked along the very same streets that you do, their poetic metaphors suddenly find a place in the history of time. Boris Pasternak was one such poet who served as a chronicler of his time. February 10 marks the 125th anniversary of his birth.

The house at 17 Lavrushinsky Pereulok, where Boris Pasternak lived starting in the late 1930s, is directly across from the Tretyakov Gallery. Not far from there on Pyatnitskaya Ulitsa lived the parents of a close family friend. One of their neighbors was a girl who once fell madly in love with my grandfather, the composer who 10 years later would become friends with this abovementioned and now longtime friend of our family while studying at the music composition department of Moscow State University. Rounding out this chain of coincidences, my grandfather was a student Heinrich Neuhaus, a close friend of Pasternak. So I have heard a lot of stories about Pasternak since childhood.

His presence, it seems, evoked awe among all of Neuhaus’s students, and perhaps that’s why in my grandfather’s recollections of Pasternak were always unbelievably vivid and lively. The poet would frequently stop by the pianist’s flat, where students often gathered, and read his verse… The fact that Pasternak had run off with Heinrich Neuhaus’s wife apparently did not impact their friendship.

“I haven't read Pasternak, but I condemn him”

Up to the mid-1930s there was a short period of “official recognition” of Pasternak’s work – he even wrote a few poems wish praised Stalin. Following the end of the Great Patriotic War Pasternak took to writing a novel which would quite reasonably later be called the height of his prose writing. After finishing his novel, Pasternak earned himself enemies everywhere, both at the state level and among colleagues.

“I haven't read Pasternak, but I condemn him” — various variations on this phrase, which was supposedly proclaimed by the middling writer Sofronov, were heard at the meeting of the Writers Union when the case against Boris Pasternak’s was considered following the publication of Doctor Zhivago.

Pasternak’s novel, which he considered his crowning achievement and which he spent an entire decade writing, not only received great acclaim in the West but on October 23, 1958, it earned him the Nobel Prize for Literature “for his important achievement both in contemporary lyrical poetry and in the field of the great Russian epic tradition”.

Despite the onset of the period which was optimistically called “the thaw”, Nikita Khrushchev and his entourage reacted very negatively to this event. The October Revolution was still a sacred occurrence which could only be spoken of reverently.

The rancor was not surprising: after the novel was rejected by several major Soviet journals, Pasternak immediately handed copies of the novel to Western publishers. That fastest of them all turned out to be the Italian Giangiacomo Feltrinelli, who managed to get an Italian version of the novel printed in 1957. Although the print run was not very large, the news about the rebellious writer quickly made its way around literary groups and then through the government.

“How wonderful to be alive,” he thought. “But why does it always hurt?”

(Doctor Zhivago)

Under great duress from persecution in the USSR, Pasternak was forced to decline the award. Naturally, he could not resist writing a verse about this titled “The Nobel Prize”.

Like a beast in a pen, I'm cut off

From my friends, freedom, the sun,

But the hunters are gaining ground.

I've nowhere else to run.

Pasternak was sure to have known that his novel would not be viewed with indifference. As his son Evgeny wrote in his memoirs, already in 1948, seven years before he finished the novel, a printing of a collection of poems which included several verse from Doctor Zhivago was destroyed. The poems apparently were strongly disliked by Alexander Fadeyev, head of the Soviet Writers Union: “In 1949 there were rumor of Pasternak’s impending arrest, and Olga Bergholz and Anna Akhmatova called from Leningrad to express their concern.” Fortunately, Pasternak was not imprisoned. Apparently out of fear of creating an international scandal.

“Just think what a time it is now! And you and I are living in these days! Only once in eternity do such unprecedented things happen. Think: the roof over the whole of Russia has been torn off, and we and all the people find ourselves under the open sky. And there’s nobody to spy on us. Freedom!”

(Doctor Zhivago)

No long ago the Central Intelligence Agency partially declassified documents concerning how anti-Soviet propaganda work was carried out in the West. It turns out that Doctor Zhivago, without the desire and without the knowledge of the author, was considered good bait for the enormous number of people who doubted the merits of the Soviet system. And, naturally, the CIA made use of this opportunity.

From 1958 to 1991 approximately 10 million copies of the novel were distributed in Eastern Bloc countries. In 1965 a film based on the book was released and went on to win five Oscars.

As soon as the book made its way, with a little help from Feltrinelli, to the Soviet desk of the CIA, and internal memo was immediately drafted. The memo notes that the book has great propaganda value, “not only for its intrinsic message and thought-provoking nature, but also for the circumstances of its publication. We have the opportunity to make Soviet citizens wonder what is wrong with their government, when a fine literary work by the man acknowledged to be the greatest living Russian writer is not even available in his own country in his own language for his own people to read.”

In order to nominate the book for the Nobel Prize, the committee had to be presented with the publication in its original language. With great cunning, and perhaps a little help from the British secret services, a manuscript in Russian was secured and published in The Hague. It is not clear how the CIA pressured the Nobel prize committee. However, the participation of intelligence agencies in the choice of Pasternak has been asserted by some, including the influential Spanish newspaper ABC, which hints at the role of one of the members of the Swedish academy Dag Hammarskjöld, who also held the position of UN Secretary General at that time.

However, the CIA did not really succeed in their goal “to make Soviet citizens wonder what is wrong with their government”. Just one book, even a very good book, was not enough to bring down the Iron Curtain, and most Soviet citizens remained unaware of these great efforts on their behalf by American counterpropaganda. A decade later a similar story occurred with Alexander Solzhenitsyn, who received the Nobel Prize in Literature “for the ethical force with which he has pursued the indispensable traditions of Russian literature”.

He like Pasternak also declined the prize, fearing reprisals in his homeland. The persecution began nonetheless. Eventually he was accused of treason and kicked out of the country. When there was nothing left to fear, in 1974, he received his well-deserved award. On December 9, 1989 historical justice also triumphed with regard to “Doctor Zhivago”. The Nobel Prize was presented in Stockholm to the writer’s son Evgeny Pasternak.

But you yourself must not distinguish

Your victory from your defeat.

(“It’s not becoming to be famous...”)

Anna Genova

It sometimes seems that people in the world of arts live outside time. And it’s true that few are interested in the socio-political situation in the time of Dante, Goethe or Apuleius… But when you look back the people who just recently lived and walked along the very same streets that you do, their poetic metaphors suddenly find a place in the history of time. Boris Pasternak was one such poet who served as a chronicler of his time. February 10 marks the 125th anniversary of his birth.

It sometimes seems that people in the world of arts live outside time. And it’s true that few are interested in the socio-political situation in the time of Dante, Goethe or Apuleius… But when you look back the people who just recently lived and walked along the very same streets that you do, their poetic metaphors suddenly find a place in the history of time. Boris Pasternak was one such poet who served as a chronicler of his time. February 10 marks the 125th anniversary of his birth.