The exposition “Russian Berlin: Russian Culture in Berlin in the 1920s” has opened at the Russian Embassy in the German capital.

The Russian Embassy is located in the heart of the German capital, on the legendary Unter-den-Linden, in a nice landmark of historic architecture. Every week its halls are visited by numerous tourists – the diplomatic mission partly functions as one of Berlin’s museums. It is here in its famous halls, Domical and Armorial, that the exposition

The Russian Embassy is located in the heart of the German capital, on the legendary Unter-den-Linden, in a nice landmark of historic architecture. Every week its halls are visited by numerous tourists – the diplomatic mission partly functions as one of Berlin’s museums. It is here in its famous halls, Domical and Armorial, that the exposition “Russian Berlin: Russian Culture in Berlin in the 1920s”

has opened.

The concept of Russian Berlin is the dialogue with two famous Russian men of letters who were Berlin residents at the time: Nabokov and Khodasevich.

Khodasevich ironically called the German capital that hosted the Russian émigrés “the stepmother of Russian cities”. Preservation of the Russian culture in emigration is one of the exposition’s themes. The second motif is in a sense a contraposition to Nabokov’s thought that Russian Berliners had no motivation to seek closer relationship with Germans, because they were preoccupied only with their own cultural life. Many exhibits demonstrate the influence which Russian immigrants started exerting on the social, cultural and academic aspects of the German society.

This is already the third exposition at the Russian mission organized by historian and cultural expert Andrei Chernodarov, a compatriot currently residing in Germany.

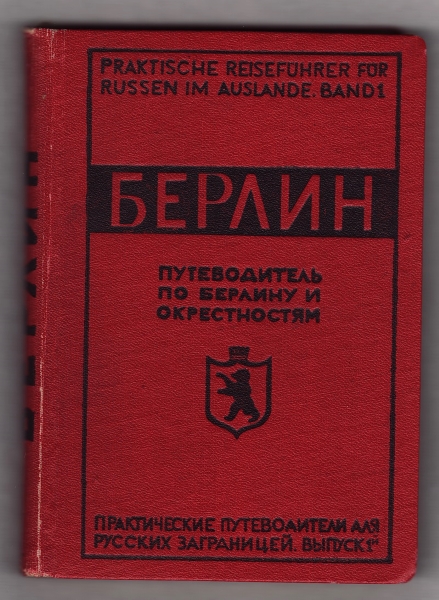

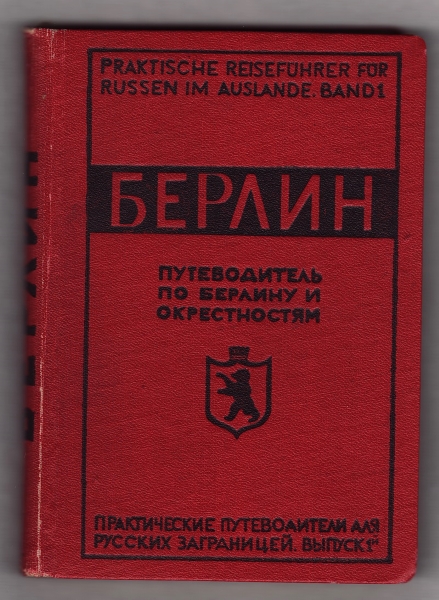

“A good tradition has developed to hold exhibitions at the Russian Embassy, to highlight the rosy aspects of our joint history. The first such exposition ‘Power, Splendor and Grandeur’ was devoted to the coronation of Alexander II and Maria of Hesse in 1856. The second one titled ‘Benign Peace onto Earth’ was devoted to the 200th anniversary of the union of Prussia and Russia against Napoleon. And now we are inviting the city-dwellers and guests to the exposition ‘Russian Berlin: Russian Culture in Berlin in the 1920s’,” says Mr. Chernodarov. “I always try to take original artifacts of the epoch for any exposition, which can be found on the spot here in Germany. We use whatever is found in private and public collections, museums (normally from special collections that have never been exhibited), rather than bringing anything from Russia. We’ve already made a lot of discoveries. They just wait for the right time to be disclosed. Thus the general public has never seen the collection of Motanovich – postcards on the Russian theme or postcards released by Russian publishers. It’s a unique collection with no analogues. Everything was selected with great love and can be seen only once here.”

The “Russian Berlin” exposition will be open till the beginning of the Christmas vacations in Germany. You need only to sign up in advance for the tour to be personally guided by the main curator. Andrei Chernodarov willingly answered the questions of the Russkiy Mir and related the specifics of the Russian life in Berlin.

— Andrei, why was this historic period chosen for coverage?

— The theme of Russian immigration of the 1920s is multifaceted, but has been studied only superficially until now. There are very few academic works – I can mention only the thesis of Thomas Urban on the theme of Russian writers in Berlin. It would be good, “through the lenses” of a cultural dialogue, to look at our joint history now and to awaken interest in this subject, since it is very exciting and gripping, and this is part of Berlin’s history.

The Berlin of the 1920s represented a twist of history: the bloody and woeful First World War where Russia and Germany were fighting on different sides of the front had just ended. At the same time Russia went through two revolutions in February and October of 1917, and Berlin all of a sudden became the place that sheltered a huge number of Russians. The city played a tremendous role in strengthening the cultural ties and preservation of the cultural tradition of Russian intelligentsia.

The Russian cultural community, including émigrés, and Russian literature were not divided in those days: those who stood on different sides of the barricades stuck together, warming the new city and spending their days together. That community not only included political immigrants but also people with Soviet passports. The German elite that upheld transformations going on in Russia rallied around the then Ambassador of Russia Nikolai Krestinsky, Thomas Mann being one of the group’s members.

But of course, the Civil War continued on the pages of such Russian periodicals as Dni, Nakanune or Rul. For example, Alexander Kerensky, former Prime Minister of the Interim Government, worked as a political columnist and editor of the Nakanune newspaper. At the same time Gorky and Mayakovsky, frequent visitors to Berlin, had their works printed here. Yesenin also stayed for several weeks in Berlin, with all newspapers filled with reports on the incidents connected with his name. Both Yesenin and Duncan seemed to deliberately heat up the press’s interest in their personalities in every way possible.

The golden time for the Russian cultural life occurred in the very beginning of the decade, from 1921 to 1924, prior to the monetary reform in Germany. This all waned over time and yet until 1930 the Russian expat community in Berlin had been very active. At the exposition you may trace down the life of the Russian community since its very first steps. Many of those who came here were positive that they had arrived just for a couple of weeks: Bolsheviks will vanish, everything will come down and they’ll return to their homeland. First Russian business appeared here in the early 1920s: porcelain factory, production of records, Russian schools. First NGOs were registered. There were several big theatre troupes, with “Blue Bird” standing out among them: they made records of their performances and were very popular.

At the height of Russian emigration there were about 400,000 Russians living in Berlin. Both now and in the previous century Russians, in the eyes of Germans, were all who spoke Russian, whether this was Chagall from Vitebsk, or Kiev-born Vertinsky, or Semyon Dubnov from Mogilev.

— Did Russians have their favorite places in Berlin? Are there any districts in Berlin that could be called “Russian”?

— Did Russians have their favorite places in Berlin? Are there any districts in Berlin that could be called “Russian”?

— On display here is the map of Russian Berlin addresses. Berlin’s ancient district Scharlottenburg was simply renamed into Scharlottengrad because of its big concentration of Russians. For some time even the name of the famous Kudamm (Kurfürsterdamm) was changed to NEPsky Avenue after Lenin’s NEP and in commemoration of Nevsky Avenue.

A magic triangle for Berlin’s Russian community of that era took shape in the area of Keiserin-Augusta Platz – Nollendorf-platz – Wittenbergplatz. We present a rather rare book at our show: Petersburg in Wittenberg Square. It is here that an intense night life could be found in Russian salons and cafes.

The most popular place was the Prager Diele café, a must-visit for all new Russian arrivals. Andrei Bely even tried to introduce the “pragerdielerism” neologism in German and Russian, to stand for speculating and philosophizing about the Russian reality in clouds of smoke and with a glass of cognac.

This café was perfect for all representatives of the Russian community – some of its frequenters left Russia for political reasons, while others worked in Berlin with Soviet passports, like Ilya Erenburg. He had a Soviet passport and his own table at the café, where he set up his typewriter and worked.

Regrettably all of this history dissipated and today you won’t even find any signs indicating the places where Nabokov and Gorky once lived.

Interviewer: Elena Eremenko

The Russian Embassy is located in the heart of the German capital, on the legendary Unter-den-Linden, in a nice landmark of historic architecture. Every week its halls are visited by numerous tourists – the diplomatic mission partly functions as one of Berlin’s museums. It is here in its famous halls, Domical and Armorial, that the exposition “Russian Berlin: Russian Culture in Berlin in the 1920s” has opened.

The Russian Embassy is located in the heart of the German capital, on the legendary Unter-den-Linden, in a nice landmark of historic architecture. Every week its halls are visited by numerous tourists – the diplomatic mission partly functions as one of Berlin’s museums. It is here in its famous halls, Domical and Armorial, that the exposition “Russian Berlin: Russian Culture in Berlin in the 1920s” has opened. “A good tradition has developed to hold exhibitions at the Russian Embassy, to highlight the rosy aspects of our joint history. The first such exposition ‘Power, Splendor and Grandeur’ was devoted to the coronation of Alexander II and Maria of Hesse in 1856. The second one titled ‘Benign Peace onto Earth’ was devoted to the 200th anniversary of the union of Prussia and Russia against Napoleon. And now we are inviting the city-dwellers and guests to the exposition ‘Russian Berlin: Russian Culture in Berlin in the 1920s’,” says Mr. Chernodarov. “I always try to take original artifacts of the epoch for any exposition, which can be found on the spot here in Germany. We use whatever is found in private and public collections, museums (normally from special collections that have never been exhibited), rather than bringing anything from Russia. We’ve already made a lot of discoveries. They just wait for the right time to be disclosed. Thus the general public has never seen the collection of Motanovich – postcards on the Russian theme or postcards released by Russian publishers. It’s a unique collection with no analogues. Everything was selected with great love and can be seen only once here.”

“A good tradition has developed to hold exhibitions at the Russian Embassy, to highlight the rosy aspects of our joint history. The first such exposition ‘Power, Splendor and Grandeur’ was devoted to the coronation of Alexander II and Maria of Hesse in 1856. The second one titled ‘Benign Peace onto Earth’ was devoted to the 200th anniversary of the union of Prussia and Russia against Napoleon. And now we are inviting the city-dwellers and guests to the exposition ‘Russian Berlin: Russian Culture in Berlin in the 1920s’,” says Mr. Chernodarov. “I always try to take original artifacts of the epoch for any exposition, which can be found on the spot here in Germany. We use whatever is found in private and public collections, museums (normally from special collections that have never been exhibited), rather than bringing anything from Russia. We’ve already made a lot of discoveries. They just wait for the right time to be disclosed. Thus the general public has never seen the collection of Motanovich – postcards on the Russian theme or postcards released by Russian publishers. It’s a unique collection with no analogues. Everything was selected with great love and can be seen only once here.” The Russian cultural community, including émigrés, and Russian literature were not divided in those days: those who stood on different sides of the barricades stuck together, warming the new city and spending their days together. That community not only included political immigrants but also people with Soviet passports. The German elite that upheld transformations going on in Russia rallied around the then Ambassador of Russia Nikolai Krestinsky, Thomas Mann being one of the group’s members.

The Russian cultural community, including émigrés, and Russian literature were not divided in those days: those who stood on different sides of the barricades stuck together, warming the new city and spending their days together. That community not only included political immigrants but also people with Soviet passports. The German elite that upheld transformations going on in Russia rallied around the then Ambassador of Russia Nikolai Krestinsky, Thomas Mann being one of the group’s members. — Did Russians have their favorite places in Berlin? Are there any districts in Berlin that could be called “Russian”?

— Did Russians have their favorite places in Berlin? Are there any districts in Berlin that could be called “Russian”?