![]() — Russkiy Mir Foundation — Journal — Articles — The Crossroads Between East and West

— Russkiy Mir Foundation — Journal — Articles — The Crossroads Between East and West

The Crossroads Between East and West

The Crossroads Between East and West

In the 15th century, the first Russian diplomatic mission visited the city of Herat, one of the capitals of Tamerlane’s empire, which consisted of Afghan lands.

This land of mountains, deserts and oases has truly been ravaged by countless wars, and through this land many great armies of antiquity have passed. In different periods it has been conquered by the Achaemenid Empire, Alexander of Macedon, the Seleucid Empire, the Parthians, the founders of the Kushan Empire – the Tocharians, the Sassanid Empire, and Tamerlane. It was a descendant of the latter – the military leader, poet and writer Zahiriddin Muhammad, known as Babur (Tiger) – who made his capital in Kabul. In 1526, he also founded the Mughal Empire, moving his residence from Kabul to Delhi. But it was eighteen years before the birth of Babur when the first Russian ambassadors visited this land – which had yet to carry the name of Afghanistan.

From Moscow to the Hindu Kush

In the 15th century, the first Russian diplomatic mission visited the city of Herat, one of the capitals of Tamerlane’s empire, which consisted of Afghan lands. This happened during the reign of Ivan III, in 1465, and, as stated in the chronicles, the Russian mission arrived with “an expression of love and a desire for friendship” and was met honorably by the ruler of Herat, Abu Said. In 1490, ambassadors from Herat arrived in Moscow on a similar visit, although this voyage failed to stimulate the development of Russo-Afghan relations.

In the next century a new attempt to establish bilateral relations was made: in 1532, when Khoja Hussein arrived in Moscow with a letter and an offer of friendship and brotherhood from Zahiriddin Muhammad Babur. However, Babur died in 1530 – before his mission even got to Moscow...

Meanwhile, the Persian Shahs of the Safavid dynasty entered the struggle for control over Afghan territory; from their domination the Pashtuns managed to escape only in the first half of the 18th century. It was then on this land, where feudal relations had just begun to take shape, that an independent state began to form. It is true that independent Afghanistan in its present form has been in existence for only ninety years, but the country’s name itself became stuck in the international political vocabulary in the middle of the 19th century largely due to Friedrich Engels.

Up until the beginning of the 20th century, bilateral relations were limited mainly to trade and economic contacts. However, in the same period there were many informal contacts of missions, merchants and travelers, some of whom remained in Afghanistan. Precise data on the number of Russian newcomers were never preserved, however. Russian voyages to the “Land of Afghans” occasionally gave rise to international conflict. For example, the reason for Britain’s invasion of Afghanistan in the 1830s was a trip by Lieutenant Ivan Vitkevich to the country. Vitkevich’s fate reads like a gripping detective novel. Incidentally, Vitkevich was the subject of Yulian Semyonov’s first story – Diplomatic Agent.

A secret agent and a brilliant diplomat

Ivan (Ian) Vitkevich was born in Vilnius in 1808. In 1823, a secret antigovernment sect known as the “Black Brothers” was uncovered at the gymnasium where he was studying. As punishment for participating in it Vitkevich was deprived of his noble status and sent to serve in Orsk as a soldier in the 5th Line Battalion of the Orenburg Corps. Within a few years of service, the young Pole had mastered Persian, Kazakh and Uzbek. In addition, he knew English, French and German. When the famous German naturalist Alexander von Humboldt visited Orenburg in 1829, Vitkevich served as his interpreter. Humboldt was imbued with a sense of sympathy for his assistant, and on arriving in Orenburg he interceded before the governor on the educated soldier’s behalf. From that moment, Vitkevich’s fate changed dramatically. He was transferred to Orenburg, and in 1831 he was already working as a translator for the border commission. In 1836, Vitkevich arrived in Bukhara where he worked to collect information on the situation in Central Asia, explore the relationship between the khanates, collect information about British agents while at the same time negotiating with the ministers of the Emir of Bukhara and urging them to side with Russia... In the fall of 1837, near Herat, an employee of the British Embassy in Persia was horrified to find an order of Cossacks led by the young Vitkevich, who had arrived in Kabul on a diplomatic mission in December of that year. We should note that the British viewed the Russian mission as being very dangerous – just like the entire Russian Empire at the time. The overall tone of London newspapers at the time with respect to Russia boiled down to the “Russian devil” always “annoying” the peaceful British Empire through their “scams” and “antics.”

Meanwhile, Vitkevich made a very favorable impression on Dost Mohammad Khan, and despite strong opposition from the British, the Kabul governor accepted the offer of an alliance with Russia. In 1838, Britain's Ministry of Foreign Affairs issued a strong protest to Russia's ambassador in London in connection with Vitkevich’s activities in Kabul. In 1839, Vitkevich arrived in St. Petersburg, where after nine days he was found shot dead in the hotel room where he was staying. The extensive archive that he had brought along disappeared.

It was Vitkevich’s mission to Kabul, the beginning of negotiations with Dost Mohammad and the relocation of the Persian troops – conducted under the influence of Russian diplomats – which unleashed the first of three Anglo-Afghan Wars (1838-1842).

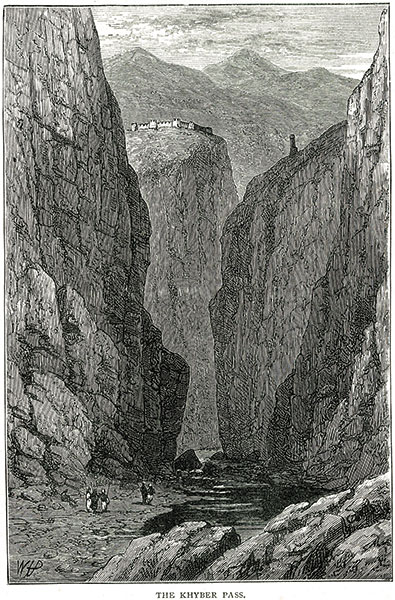

Why is Afghanistan so important? Why have different peoples constantly been fighting over this territory? The answer to these questions must be sought in country’s geographical position. After all, Afghanistan is at the crossroads of routes linking Iran, Central Asia, India and the western part of China.

A struggle over interests

The constant rivalry between Russia (and later the Soviet Union) and the Western powers for influence in Afghanistan has meant that for nearly a century, beginning at the end of the 19th century, Russia's policy with respect to that country has been aggressive in nature. The goal of imperial and Soviet foreign policy was to impose influence on its southern neighbor and, occasionally, its own model of political and economic development. On the other hand, the history of Russo-Afghan relations also saw periods of good-neighborliness and mutually beneficial cooperation.

Thus, with Afghanistan’s proclamation of independence in 1919, the first power to recognize the new Afghan state was Soviet Russia. In 1921, the two countries signed a treaty of friendship. In the post-revolutionary period, the backbone of the Russian diaspora in Afghanistan was made up of people who had escaped Soviet Russia. Afghanistan began receiving Soviet financial and military aid, and Soviet-Afghan trade began to increase. Cultural exchange was instituted between the two countries. The first Soviet specialists appeared in Afghanistan, and with their help the country saw a communication network – the telegraph and telephone – put in place.

Economic and trade cooperation between Afghanistan and the Soviet Union developed quite smoothly until the early 1930s when the despotic regime of Nadir Shah came to power. As a result, Moscow gradually lost interest in Afghanistan, limiting communication to diplomatic contacts. As a result, the small Russian diaspora in Afghanistan almost completely disappeared.

After the Second World War and particularly since the mid-1950s, relations between the two countries underwent radical changes that had a direct impact on the number of Russians living in Afghanistan. In 1954, a Soviet-Afghan agreement was signed on the building of a bread factory and asphalt plant in Kabul that would employ Soviet technical expertise. In 1956, an agreement on military assistance was signed, and, finally, in 1959, during Afghan Prime Minister Mohammed Daoud’s visit to Moscow, an agreement was signed to expand the scale of Soviet-Afghan cooperation. In the same year the Soviet Association for Friendship and Cultural Ties with Afghanistan was established. Soviet engineers were sent to Afghanistan to expand the country's major transportation route – the road running from Kabul to the Soviet Union through the Salang Pass. In Bagram, Shindand and Maz

However, by the end of the 1970s, Moscow was trying to fill with its presence every imaginable and unimaginable sphere of Afghanistan’s sociopolitical, social, economic and cultural life. At the Kabul Polytechnic Institute, for example, a Soviet plumbing advisor was employed. An advisor on pastures worked at the Ministry of Agriculture. Even in the establishment of the Pioneer Organization of Afghanistan the Soviet Union played a great role.

A war without end

In the spring of 1978, the Saur Revolution took place in Afghanistan, which brought to power the People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan, a pro-Soviet government. The country was renamed the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan, and it was announced that all forms of exploitation of the peasantry would be eliminated. Introduction of state control over the economy was also announced, and the equality of women and minorities was proclaimed. A policy to eliminate illiteracy was also declared. The new government’s reforms led the country into chaos and civil war. As a result, at the very end of 1979, the Kremlin leadership made the fateful decision to send Soviet troops in Afghanistan. For the USSR, the Afghan war actually began on December 27, 1979, and according to an evil twist of fate, this took place during the storming of the palace of Afghan President Hafizullah Amin, who, in fact, not only made an appeal for Soviet troops to enter the country, but even managed to approve this invasion. The storm against Amin’s palace went down in all the textbooks as an example of the brilliant operations of special purpose units. Amin was killed as a result of the operation.

It is known that the introduction of a “limited contingent” did not lead to a stabilization of the situation in Afghanistan; on the contrary, the situation in the country heated up dramatically and gave strong impetus to the guerrilla war, which was inspired and actively supported from the outside. As a result, nearly 15,000 people were killed, and in 1989, Soviet troops were forced to leave Afghanistan.

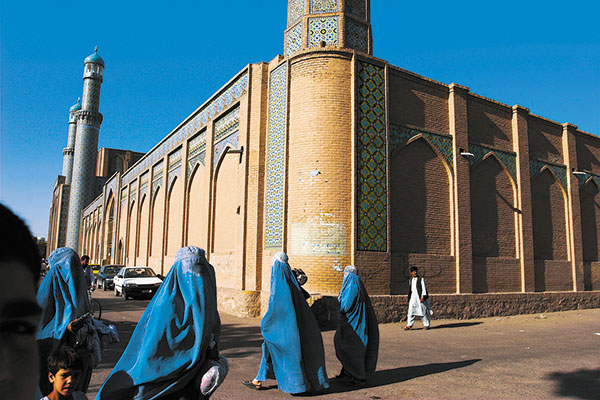

After the withdrawal of Soviet troops, the situation in the country deteriorated further. By the mid-1990s, the radical Islamist Taliban had won the country’s civil war. On September 29, 1996, the Taliban proclaimed the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan. However, in late 2001, after the terrorist attacks in New York which were blamed on Osama bin Laden who was in hiding in Afghanistan, the Taliban were driven from Kabul and again turned to guerrilla tactics. In 2004, Hamid Karzai, who had aligned himself with the occupying NATO forces, became the country’s president. The civil war in Afghanistan continues to this day, and the Taliban are once again standing at the gates of Kabul...

Of course, we can hardly talk about a normal Russian diaspora functioning in Afghanistan in such circumstances. Over the past twenty years it has declined tenfold: of the 15,000 people living in the country at the time Soviet troops entered, 90% have left the country. Afterwards, there were about 1,500 people who for various reasons could not live outside Afghanistan. This figure is constantly decreasing.

It is interesting to note that despite the dramatic reduction in the size of the Russian diaspora, Afghanistan is still the leader (at least in Asia) in terms of the number of people who speak Russian. Today, that figure is 100,000, which is not surprising given that Russia and Afghanistan have enjoyed long-standing and good relations in the field of education. Many thousands of professionals in various fields were trained in Soviet institutions to work in Afghanistan. At present, especially given the conditions of life in the country, there is every reason to believe that the study of Russian in the new Afghanistan is going through a period of recovery. Hundreds of Afghan university students are studying Russian language and literature, and their number is constantly growing. At Russia’s institutions of higher education, some 300 Afghan nationals are currently receiving training. There is also demand for Russian language studies in Afghanistan itself. At the country’s leading institution – Kabul University – nearly 200 students are learning Russian. With regard to the structural organization of the Russian diaspora, it is virtually absent given its small size and the relatively tight control imposed by the Afghan government on foreigners. Russian and Russian-language media and other organizations in Afghanistan were eliminated following the withdrawal of Soviet troops. The same applies to Christianity. After the Taliban’s rise to power, Christians were either killed or fled underground. In June 2001, the head of the Taliban, Mohammed Omar, even banned use of the symbol of Christianity, the cross. Fundamental change for the better has not happened since the overthrow of the Islamist regime. Today, in connection with the severe economic and political situation, which is compounded by the lack of a sustained central government, the presence of international military forces, and the regular bombing of Afghan cities, an increase in the size of the Russian diaspora in Afghanistan and the creation of any diaspora organizations are impossible.

On the other hand, there are some signs of impending change for the better. For example, since 2004, specialists from Russia have helped to create an ethnographic museum in the ancient city of Herat. Another example occurred in December 2007 when the Russian embassy in Kabul hosted a conference on “Russian Studies in Afghanistan: Past, Present and Future,” in which Russian philologists from across the country took part.

If peace ever comes to the harsh land of Afghanistan, we can hope for the revitalization of the country’s Russian diaspora. Meanwhile, virtually its sole representatives are members of humanitarian missions helping people in a country still being ravaged by thirty years of civil war...

Afghanistan: facts and figures

The country shares borders with Pakistan, Iran, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, China and India. According to the first general census of 1979, the Afghan population was 15.5 million people. According to estimates in 2003, the population is about 29 million people.

Approximately 40% of the population belong to the Pashtun tribes, 25% are Tajiks, 19% are Hazara, 9% are Uzbeks and 3% are Turkmens. The official languages of Afghanistan are Pashto and Dari (the Afghan dialect of Farsi).

Because of the fighting that continued for almost thirty years, the country's economy fell into total decline. A huge number of refugees from Afghanistan are still in Iran and Pakistan. In 1979, the Academy of Sciences of Afghanistan was founded.

The National Museum in Kabul once held a particularly valuable collection of prehistoric, Greek and Buddhist artifacts. In 1993, however, when the museum fell into the zone of fighting, most of the collection was looted.

Author: Alexander Naumov