Pushkin: Our Everything

/ Главная / Russkiy Mir Foundation / Publications / Pushkin: Our EverythingPushkin: Our Everything

Marina Bogdanova

From early childhood on, every Russian learns to recognize his face in even its most stylized representation. His fairy tales are among the first things that Russians remember from their childhood. In a well-known test, when people are asked to quickly name any flower, fruit, and Russian poet, 98% respond: “red, apple, Pushkin.” Even a person who has no interest in literature will remember that Pushkin is the “sun of Russian poetry” and “our all.”

It’s no coincidence that there was even a decision to celebrate the International Day of the Russian Language at the UN on Pushkin’s birthday from 2010 onward (just as the Day of English Literature is on Shakespeare’s birthday, and that of Spanish Literature is on the day of Cervantes’s death). One year later, in 2011, a presidential decree was issued to celebrate the Day of the Russian Language in Russia as well. Since then, Pushkin, the greatest genius of Russian poetry, and the Russian language were not simply linked but practically blended into one. But has it always been this way?

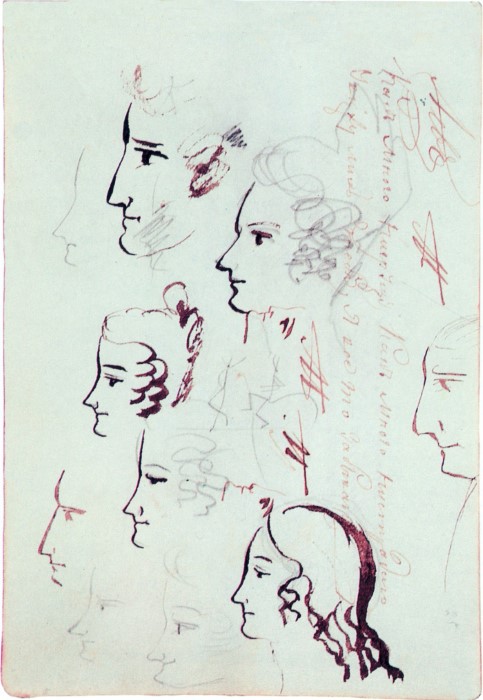

Drawing by A.S. Pushkin in the album of E. Ushakova. Male and female profiles

Even during his life, Pushkin was called a genius and the top Russian poet (and not for a lack of contenders—there were quite a few!). The Emperor Nikolai I observed after granting an audience to Pushkin: “Now I have had a long talk with the most intelligent man in Russia.” Nonetheless, the poet’s contemporaries would hardly have believed that two centuries later Pushkin would become an idol and the symbol of Russian literature—that he would be raised to an almost godly rank. In Pushkin’s time, there were writers and poets who were considered more deserving, more dignified, and more popular than Pushkin—or at the least, no worse than he. But what of it? These contemporaries can be forgiven: as they say, no one is a prophet in their own hometown.

Hannibal’s Great-Grandson

In 1799, at the close of the 18th century, the Pushkin family welcomed a new son, Alexander. Now any representative of the ancient and renowned Pushkin family is associated with this same Pushkin, but at the time of young Alexander’s birth, his uncle Vasily was considered the writer among the Pushkins. He was a playwright, a poet, and a friend and interlocutor of the poets Gnedich, Derzhavin, Zhukovsky, and Karamzin. At a later time, when he needed to settle his nephew at the Lyceum, these connections would turn out to be extraordinarily useful.

Pushkin’s mother, a “beautiful creole” as she was called in society, was the granddaughter of Peter the Great’s favorite and grandson Ibrahim Hannibal, and on her mother’s side she belonged to the Pushkin clan. She was related to her future husband, Sergei, but she was a distant relation. Alexander’s grandmother, Maria Alexeevna Hannibal, lived apart from her husband for 30 years, having left him with her little daughter Nadezhda. The quick-tempered and unrestrained Osip Abramovich was convinced (and he wasn’t alone in this) that his daughter Nadezhda wasn’t his daughter at all: from childhood onward her features didn’t show any African heritage. Very often, the Prince Alexander Vizapur, of Indian descent, is identified as Nadezhda’s father—and consequently as Pushkin’s true grandfather. True, judging by documents, Vizapur was only eight years old at the time the Hannibals were married, but such details don’t deter mythmakers: after all, the young Vizapur could have had an elder relation.

Drawing by A.S. Pushkin in the album of E. Ushakova. Self-portrait

It’s well known that Pushkin’s mother didn’t like her clumsy and strong-willed elder son, though some kind of human interaction did begin to take place between them when Nadezhda Osipovna grew old and her son sincerely cared for her. But when Pushkin fell into disfavor and was exiled, it was Nadezhda Osipovna who knocked on every door in an attempt to gain a lighter sentence for her wayward and brilliant child. Pushkin remembered this very well.

It is widely believed that Pushkin was raised by his nanny, Arina Rodionovna, but this isn’t the case. Arina Rodionova cared for his sister, and then for his little brother. Pushkin listened to her songs, fairy tales, and other pearls of folk wisdom when he was already grown, whiling away the winter evenings with the old woman during his exile at Mikhailov. His grandmother, Maria Alexeevna, was the true angel for “klutzy Sasha.” According to the recollections of Moscow memoirist E.P. Iankova, “The Pushkins lived happily and openly, and household affairs were mainly conducted by the old lady Hannibal, a very smart, practical, and reasonable woman. She knew how to do things the right way, and she was also more involved with the children: she brought in teachers for them and taught them herself.” It was his grandmother who told Sasha fairy tales every night, taught him to read, instructed, scolded, and spoiled him.

Fidget

At the Lyceum, they called this loud and impulsive adolescent the Frenchman, the Monkey-Tiger, or the Fidget. His teachers and his friends caught it from him. He nearly drove the poor Wilhelm Küchelbecker to suicide with his teasing, but, fortunately, it all resolved with them making piece.

As a student, Pushkin was worse than mediocre — and to this day it is a pleasant surprise for school children on field trips to the Lyceum to see the class rankings, where Alexander Pushkin is practically in last place. As it turns out, you can achieve greatness without being a top student!

Pushkin’s mischief-making and dangerous stunts often carried a markedly rebellious character. The next generation of Lyceum students were thrilled to remember this fact, and the school’s first class were living legends to them. One time when a young chained bear cub (which had grown a good deal) broke free and accosted the Emperor Alexander I, Pushkin exclaimed in a fervor of freethinking: “There’s one real man in all of Russia—and he’s a bear.”

The freedom-loving spirit of the upper Lyceum classes was supported by their older friends—the officers of the Imperial Hussar Guard, quartered nearby, whose parties the young scholars would secretly slip out of their modest Lyceum cells to visit. At this improvised festivities, they smoked, drank, and talked about whatever they wanted. From discussions of historical and political topics they transitioned to theory and practice of a very different kind. Later, the Decembrist Yakushkin would remember, not without annoyance: “…he would pretend to be daring, likely remembering Kaverin and his other Hussar friends at Tsarskoe Selo; meanwhile, he would tell the most dire stories about himself, and all this together somehow came across as quite vulgar.”

But among these daredevils and swashbucklers Pushkin met Chaadaev. The future Moscow philosopher, who was later declared mad for his views, taught much to this impressionable and spirited young man. The latter, in his turn, showed deference to his wise and reasonable comrade, seeing in him all the ideals of antiquity at once and suffering bitterly from the fact that such a great man should lead a petty and demeaningly ordinary life. He was only an officer when he could lead nations to happiness and bestow just laws on humankind!

Through heaven’s high command,

He was born enchained by royal service;

In Rome he’d have been Brutus, in Athens—Pericles,

But here he’s just a Hussar officer.

“Shameless frenzy of desires”

After graduating the Lyceum, Pushkin, as befits a young poet of the Romantic type, let himself go. Formally remaining in the civil service, as a bureaucrat of the tenth class (a very good start for a career) and a translator in the College of Foreign Affairs, he managed to have a whole bunch of romantic affair, become a regular in every seedy establishment, establish friendly relations with the leading figures of Russian culture—all the while writing excellent verses alongside indecent rhymes.

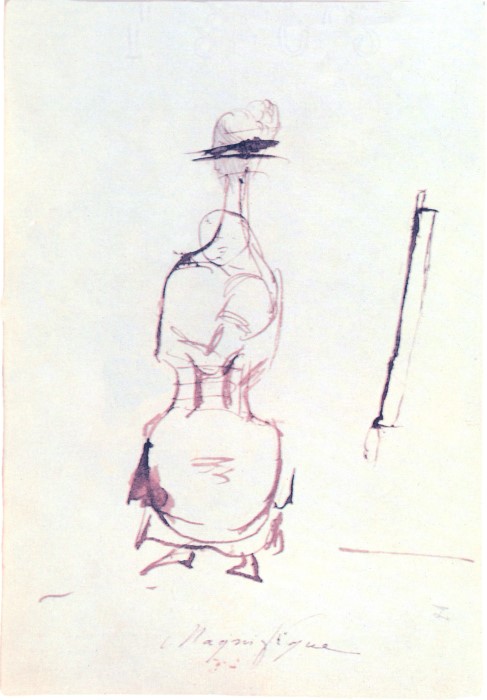

Drawing by A.S. Pushkin in the album of E. Ushakova. Cello as a feminine figure

His poem “Ruslan and Liudmila” got everyone talking about a new talent. But if the poet’s literary reputation was solidifying, his reputation as a member of society was rapidly coming apart. He participated in meetings of the quasi-legal philanthropic Green Lamp society—and in the orgiastic Saturday gatherings that took place in the same house with the same participants. He courted all the ladies at once, leaning on his unrelenting temperament. Not being handsome, and even considering himself to be ugly, he nonetheless attracted ladies with his “shameless frenzy of desires.” He “studied atheism,” and literally over one Easter week he wrote a blasphemous and hilarious narrative poem called The Gabrieliad.

He got pulled into the most foolish duels, conducting himself as stupidly and insolently as possible, especially when he was drunk, and his friends had to expend enormous efforts and energy to continually disentangle him from difficulties. One day, when his father met the poet’s best friend from the Lyceum, Ivan Pushchin, on the street, he reluctantly told Pushchin what exactly “our Alexander” was doing for entertainment. After this accidental meeting, Pushchin, a member of a Secret Society, seriously rethought the prospect of revealing his secret to his friend, and he very strictly guarded the conspiracy in conversations with Pushkin going forward.

A rumor circulated about Pushkin that he had been called into the Secret Office and flogged there for his unacceptable conduct and impudent poems. This rumor, which brought the poet to despair, was spread by his friend, Fyodor Tolstoy, nicknamed “the American,” as revenge for the fact that Pushkin had exposed him cheating at cards. In a letter to Prince A. A. Shakhovskoy, Tolstoy told him about this pacifying beating that had supposedly taken place, and the Prince, of course, retold this savory story to someone as a strict secret, without naming his source.

Pushkin was livid. He tried to find out where this shameful rumor originated. He committed follies and deliberately bombarded Tsar Alexander with epigrams so that no one would accuse him of submission or fear. Pushkin found out that the “American” was behind the gossip when he was already in exile and there was no possibility of challenging the lowlife to a duel. Of course, this was very fortunate, because Fyodor Tolstoy was a sharpshooter who had calmly killed 11 men in duels, and he most likely would have short the passionate youth dead. Subsequently, their friends managed to make peace between them.

Far from Petersburg

In a certain sense, Pushkin’s forcible removal from Petersburg was the only possible way to reign in and put in place this overly passionate poet. The poets Zhukovsky and Karamzin, along with anyone else who might hold some authority in the Tsar Alexander’s eyes, implored on Pushkin’s behalf—and his punishment was quite mild: he was simply “transferred” in the service to the southern regions and placed in the charge of General Inzov, under whose command lay all southern regions and colonies.

Pushkin’s former superior, Count Kapodistrias was forced to enumerate in a letter to the general the transgressions and offenses for which Pushkin was exiled from Petersburg—a punishment that, though it was relatively mild, made a great impact on a young man who had grown used to intellectual society. But this letter had the reverse of its intended effect on Inzov, who was educated by the Martinists, and he took the talented freethinker under his wing. Vigel describes this relationship, which in no way resembled subordination, in the following way: “From the very first moment, Inzov let this young man, who had arrived without any money, stay in his home, gave him food and drink, and showed him affection—and this was how things remained until their final separation.”

Drawing by A.S. Pushkin in the album of E. Ushakova. Self-portrait on horseback

In Bessarabia Pushkin lived as before: he wrote poems, as well as long verse narratives, fell in love, and offended local society. (One time, he appeared as a guest in lace trousers without underwear, and the young ladies were quickly removed from the room.) With Inzov’s permission, he traveled all over the Crimea and was a frequent guest at Kamenka, where he almost joined up with the conspirators who would later become the Southern Society. But Pushkin’s behavior and reputation—in spite of his genius—didn’t speak even remotely in his favor. “I didn’t like him as a person,” testified the Decembrist Nikolay Basargin, who met Pushkin at this time. “A kind of dueling personality, self-satisfaction, and a desire to deride and take jabs at others. At the time many who knew him said that sooner or later he would die in a duel.”

Pushkin, who had grown used to indulging his every desire, managed to contrive an affair with the wife of one of his hosts (one of the Davydov brothers), and he even went on to ridicule both the love-struck lady and the obtuse cuckolded husband. The difference between the Pushkin’s poems—which were glorious, profound, and Russia’s best—and his unbearable, often simply boorish conduct was massive. Later generations have preferred to forgive Pushkin for all of his escapades on account of his poems, but his contemporaries simply forbade young people to hang around such a person.

When at the request of his friends Pushkin was brought from God-forsaken Bessarabia to the more bustling and lively Odessa, his new superior, Count Vorontsov, didn’t wish to look after Pushkin the way the most kind-hearted Inzov had done for nearly two years. After a series of scandals and the censors’ discovery of a blasphemous letter, the capital’s patience came to an end—and Pushkin was sent to his family estate Mikhailovsk, on orders not to leave and under the supervision of his relatives, as well as the monitoring of the local Church hierarchy.

A New Pushkin

Here in Mikhailovsk the poet experienced a whole series of crises—and there remained no trace of his former impudent brawling and stupid bravado. The Decembrist revolt, the execution of his friends, rethinking his entire life, and finally, the difficult process of growing up and mellowing out led Pushkin to become a new person (while also remaining Pushkin). This new Pushkin turned out—unexpectedly!—to be an excellent family man, a caring father, and an attentive husband.

He engaged in deep and serious historical research and analysis. He made peace with God and conducted a correspondence with the Metropolitan Filaret. Nikolai noticed and valued the new poet, telling his court: “Now Pushkin’s mine!” He appointed himself the poet’s personal censor. Incidentally, this experiment in domesticating Pushkin failed. For his contemporaries, the poet had remained, ever since his stormy youth, something like a constant target for gossip, an inexhaustible source of witty puns, jokes, and piquant stories. In essence, they didn’t know any other Pushkin, and they didn’t want to know him.

For instance, the print run for The Contemporary, a journal organized by Pushkin, was only 600-700 copies. At the same time, the journal of his rival Bulgarin had more than 2000 subscribers. Beginning in the 1930s, the notion that Pushkin had already written his best stuff was a constant refrain among the public. The poet’s friends supported him, but the cost of living kept rising and his family kept growing—as did his stress—and he knew less and less how to live…

Nevertheless, his enemies weren’t about to let him be. Today it’s impossible to determine precisely who thought up and acted out the revolting drama of sending letters inducting Pushkin into the “Order of Cuckolds,” or why people took such pleasure in participating in this attack. The literary scholar Yuri Lotman, however, offers the following answer: “Pushkin had many enemies. It would be incorrect to imagine the world to which the poet returned in his latter years as a den of thieves or a mob of theatrical villains. However, the corrupting influence of the victory won by Nikolai I on the Senate Square would only become fully evident in the second half of the 1830s. Several months before his duel, Pushkin wrote to Chaadaev: ‘Our contemporary society is as detestable as it is stupid…’ Pushkin, who couldn’t conceive of life without a feeling of his own dignity, provoked irritation in people who didn’t have dignity or who had squandered it in various compromises with their consciences. And now, with sadistic curiosity, they observed and sped along events, expecting to enjoy the spectacle of the poet’s degradation.”

Drawing in E. Ushakova’s album. Portrait of Natalia Nikolaevna Goncharova

There was no one to stop Pushkin’s last duel. And although Pushkin was mourned in away that no other writer or poet had been—indeed, they had to remove a wall from his house so that the endless crowds of people could approach and say farewell to him—it was too difficult to evaluate Pushkin’s contribution to Russian literature fairly, because “large things can only be seen at a distance.” And then it turned out that Pushkin—the good-for-nothing unbearable and ridiculous person, who in the words of Nikolai I “was compelled by force to die a Christian death”—was “a prophet, and more than a prophet.”

Several years would pass, and then Vissarion Belinsky’s articles would force Russia to see what our Pushkin really was, why he was a treasure, and why he was specifically our treasure. And almost another half-a-century later, in his famous speech at a meeting of the Society of Lovers of Russian Literature, Dostoevsky would speak about Pushkin’s global, fantastic “responsiveness,” and proclaim that Pushkin was practically a prophet for Russia, indicating its path forward and giving the most profound answers to its eternal questions. And for Vladislav Khodasevich, a brilliant poet of the Russian Silver Age and a profound, intelligent writer, Pushkin’s name was a password and a holy relic—this would be the name “for us to call out…for us to shout to one another in the approaching darkness.” This was in the year 1921, and the darkness was becoming more and more impenetrable.

Today, the poet’s birthday is the Global Day of the Russian Language. And how could we not remember the lively, passionate, fitful, bitter, ridiculous—the true living Pushkin — on this very day?..

New publications

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.  Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.

Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.  When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.  Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."

Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."  "Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...

"Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...