Nadezhda von Meck’s Dutch Great-great-great-granddaughter

/ Главная / Russkiy Mir Foundation / Publications / Nadezhda von Meck’s Dutch Great-great-great-granddaughterNadezhda von Meck’s Dutch Great-great-great-granddaughter

Inessa Filatova

Countess Nadezhda Filaretovna von Meck was a famous nineteenth-century Russian patron of the arts. Tchaikovsky would often visit and work at the von Meck estate, and he dedicated several musical works to his “best friend” there. Nadezhda von Meck supported other musicians as well: Nikolai Rubinstein, Claude Debussy, and Henryk Wieniawski. A correspondent from Russkiy Mir met with the Dutch great-great-great-granddaughter of Nadezhda von Meck, the art photographer Nadja Willems.

Five Generations Later

“Nadezhda von Meck is my oermoeder. This is a special word signifying direct kinship along the maternal line for five generations,” Nadja Willems explains. “I am Nadezhda Johanna Maria Willems-Radsen, my mother (moeder) is Elizabeth Johanna Libertine Radsen-Telenius Krauthoff, my grandmother (grootmoeder) is Johanna Maria Bosse Van der Borch tot Verwolde, my great-grandmother (overgrootmoeder) is Helena Maria von Löwis of Menar, my great-great-grandmother (betovergrootmoeder) is Lidia von Meck, and my great-great-great-grandmother (oermoeder) is Nadezhda von Meck. They named me after her.”

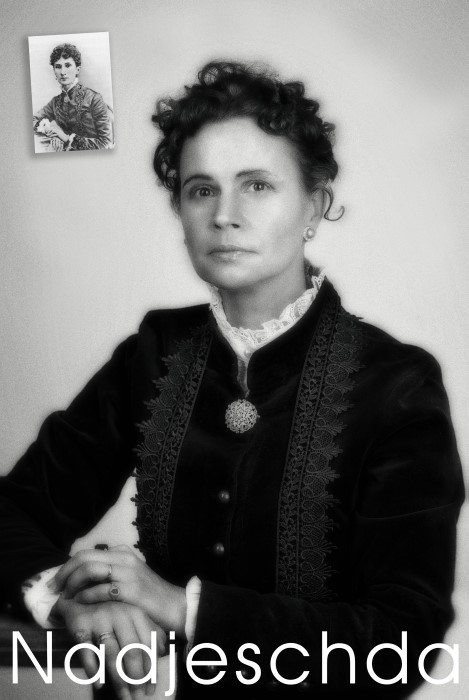

Nadjeschda (self-portrait). Courtesy of N. Willems

– Nadezhda Filaretovna mentioned her daughter Lidia in her correspondence with Tchaikovsky. “You know, my dear, that Lida sings splendidly; in addition to her wonderful silver voice, she also has complete control over it, and she is very well trained, and yesterday I spent an entire evening enjoying her singing...” (Meck to Tchaikovsky, Pleshcheevo, 22 July 1890. Author’s Note)

– Yes, Lidia’s daughter married the Dutch baron Van der Borch tot Verwolde, and they lived in the Worden manor. My mother was born at this manor. It no longer belongs to our family. My elderly uncle sold it, as he was not able to maintain it.

By the way, I’m also currently reading the correspondence between Nadezhda von Meck and Tchaikovsky in Dutch translation. We’ve had this book at home all my life, but I haven’t looked at it until now.

– But you knew about Nadezhda von Meck and her role in Tchaikovsky’s life?

– Since my childhood I knew that I was named after her and that she was very rich. And of course, when I was a child, I trembled upon seeing the beautiful outfits of that time, and it opened up for me, as it did for my two younger sisters, a world of beautiful fantasies. Mom told us that if there hadn’t been a Russian Revolution we would have been princesses. But of course, I didn’t know that she supported Tchaikovsky. That occurred much later. It was a great surprise, but nothing more. Perhaps it holds a greater significance in Russia; after all, it is a part of Russian cultural history.

“My intimate friend, both known and unknown”

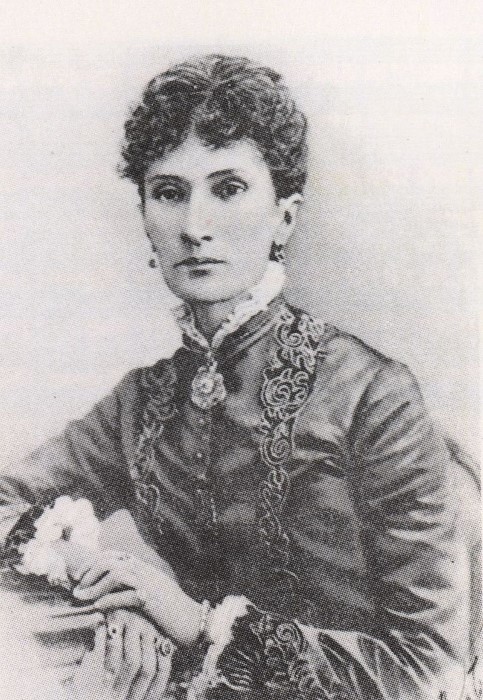

Nadezhda Felaretovna Frolovskaya (1831-1894), the daughter of a minor provincial landowner, was married at the age of fifteen to a modest railway engineer descended from the longstanding noble family of the von Mecks. When her husband retired from state service and began privately constructing railways, she helped him, taking up the responsibility for business correspondence, while also raising the eleven of their eighteen children who survived. After 15 years of hard work, Karl von Meck became a railway magnate. He died in 1876, leaving an inheritance of millions to his wife.

In December of the same year, Pyotr Ilych Tchaikovsky received his first letter from an unknown woman who expressed her admiration for his music and offered him generous compensation for taking a musical commission. At the time, Tchaikovsky was a professor at the Moscow Conservatory and the author of three symphonies, three operas, a ballet, a quartet, the overture to Romeo and Juliet, some symphonic fantasies, and several concert and chamber compositions, but he continued to experience financial difficulties and had great debts. Tchaikovsky responded and quickly fulfilled the commission. So began a lively correspondence, the official tone of which was quickly replaced by a friendly one, filled with the delicate and attentive interest of two people on intimate terms.

Nonetheless, according to Nadezhda’s wishes, they did not meet in person. “…It seems to me that not only do their relations place people on intimate terms, but even more than this, it’s their confluence of opinions, identical capacities for feeling, and a similarity in their sympathies, which means that people can be close while also being very far away,” wrote Nadezhda in a letter to Tchaikovsky on 7 March 1877. “<…> I prefer to think about you at a distance, to listen to your music and to feel that I’m together with you in it.” In their letters they would even call each other “my intimate friend, both known and unknown.”

Nadezhda von Meck set aside for Tchaikovsky an “allowance” of 6000 rubles per year, which allowed him to leave the Conservatory and devote himself entirely to his work. This money was consistently paid out until 1890, when von Meck’s finances went into decline.

In response to a letter about his payments coming to an end—and closing with the words, “remember me from time to time”—Tchaikovsky wrote on 22 September 1890: “…I am happy that right now, when you cannot share your funds with me, I can express with full force my endless, fervent gratitude, which is completely impossible to articulate in words. You yourself do not likely suspect the whole immeasurable enormity of your benevolence! Otherwise you wouldn’t have thought that now, when you have become poor, I would only remember you from time to time!!! Without any exaggeration I can say that I haven’t forgotten you and will never forget you for even a single minute, because my thoughts, when I think about myself, always and inevitably fall upon you.

“I fervently kiss your hands and implore you to know, once and for all, that no one sympathizes and shares all of your misfortunes more than I.

“Yours, P. Tchaikovskii.”

Nonetheless, their correspondence came to an end. Three years later, at the zenith of his fame, Tchaikovsky became infected with cholera and died. Three months later in Nice, Nadezhda Filaretovna von Meck died of tuberculosis.

Nadezhda von Meck

Music For Later Generations

“I’m really not a great lover of classical music,” says Nadja Willems. “Of course, my mother took us to see The Nutcracker ballet, but then I didn’t know that there was any connection between Tchaikovsky and the history of our family. I don’t really ever know what composer I’m hearing, and that doesn’t stop me from enjoying the music. Usually, I listen to “AvtoRadio” or “Classic FM,” but more than anything I like when a piano plays on its own or with the accompaniment of one or two instruments—no more—so that it’s not drowned out by the other sounds. I really like popular music, something in the style of the Eagles. When I lived in Spain, I enjoyed listening to Julio Iglesias. I like the character of Spanish music.”

– Do you play an instrument?

– As I child, I was taught how to play the recorder and the piano. But I turned out to be completely unmusical and bad at reading music. I had to practice a lot and cram, but nothing came of it. My parents had a very beautiful piano, and every evening our neighbor came to play it. She played very well. At that time I would already be lying in bed, and I fell asleep to the music. I was sorry that I couldn’t ever learn to do that myself.

I tried to teach my daughter to play the piano when she was little. But her teacher was too oriented on the outcome. So, after a year, when my daughter was already on the point of tears during the lessons, we ended her training. My son, having seen what happened with his sister, said right away that he wouldn’t study music for anything.

My Nadezhda

“I studied at the Academy of the Arts in Enschede and worked for many years in my photo studio, taking pictures on commission,” Nadja continues. “Due to the crisis, business got worse and I took up creative projects.”

- Not long ago I finished the photo project ‘Nadjeschda’ in memory of my Russian great-great-great-grandmother. I was interested in understanding my roots—in seeing and showing them through photography. Unfortunately, I was unable to find a portrait of Nadezhda von Meck by some unknown artist. Maybe such a thing exists but is part of someone’s private collection—it’s not easy to find out about such things. There’s just a black-and-white photo. And since I conceived the project as a series of portraits, I searched out pictures from that time that would have showed ladies in beautiful outfits and accessories. I photographed them and then recreated them, photographing my contemporaries in outfits and accessories that I made myself out of what I could find in antique shops.

But I didn’t just want to recreate the images of Russian women from the 19th century as accurately as possible, but also to instill in my works an epistle from the period of my childhood. I grew up in the ’80s, during the Cold War, and here, in the West, we thought that jeans were a symbol of freedom for Russians. So in my portraits, beneath the see-through skirts, you can see jeans.

– What are you working on now?

– I have several projects. In the series of collages “Emotions” I’m trying to study the emotions through which something new comes to be born. There is the series “Wrapped and thrown away”: objects to be thrown away lie on newspapers—both things that normally get thrown out and things that shouldn’t be thrown away. (In certain collages, a crucifix, a baby, and a bundle of banknotes lie atop crumpled newspapers.—Author’s Note)

The series “Recollections” includes photographs of my own youth that have become a recollection in which you can see some things with great clarity, while from other things you only remember the color or smell. I achieved an effect of diffusion and gradual disappearance with the help of water; it’s as if you are seeing it through streaming, flowing, dripping, or still water.

Incidentally, I can only do all of this thanks to my husband. He’s a financial advisor and helps me a great deal in solving all types of practical matters. He always supports me and my projects. He is my Nadezhda! (Laughs)

A Magical Winter Fairy Tale, But Very Slippery

– And what do your kids think about your art?

– My children have always, in a way, been my guinea pigs. (Laughs) Especially my daughter, because I’ve more often photographed women. Last year she finished school. Now she has a gap year before entering the institute, and she’s studying at one of the older schools in California in order to improve her English, meet people of another culture, and look at with world with different eyes. Amber wants to become an art therapist, to help people who have psychological problems with the aid of art. She draws very beautifully and is very creative in general.

Anastasija. Courtesy of N. Williams

And when he was small, my son Tijm would get very jealous when I photographed other children. Now he’s 14 and only likes music that goes, ‘Boom! Boom! Boom! Boom!’ And he’s completely uninterested in what I’m doing. It’s puberty—what can you do! (Laughs.)

– What besides photography do you like to do?

– Cooking, trying new recipes and entertaining guests. But this doesn’t mean I’m prepared to stand at the stove for hours at a time. Some day I’ll make some Russian pancakes in honor of my Russian roots. (Laughs.) And I very much love to serve a celebratory meal. Mom gave me part of a large family service for sixty place settings and silverware with the Van der Borch to Verwolde family coat of arms, which were inherited from my grandfather and divided among all of the children. It’s very beautiful, and I adore using all of it.

And I also love to travel. For instance, two years ago my husband and I were in Marrakesh, and it’s a totally different world! In Spain, I walked along the Camino de Santiago (the path of pilgrims to the grave of the apostle Jacob in Santiago de Compostela—Author’s Note). This was a surprising attempt to return myself, to the spiritual foundation of life, to an understanding of that which is truly important. One day I will certainly travel to Russia. (Laughs.) My parents have been to Saint Petersburg. It was November, snow lay on the ground, and my mom said that it was a magical winter fairy tale, but very slippery.

– What will your next project be?

– I would like to show the underside of social media. If you can’t tell people anything constructive and interact with them respectfully, just don’t publish anything—this will help make the world a better place. And I would also like to do something connected with the Russian icon. Russian icons always have images that are very beautiful and at the same time very powerful. I would like to try to recreate these images in photographs.

New publications

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.  Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.

Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.  When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.  Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."

Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."  "Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...

"Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...