Velimir Khlebnikov: A Restless Wanderer

/ Главная / Russkiy Mir Foundation / Publications / Velimir Khlebnikov: A Restless WandererVelimir Khlebnikov: A Restless Wanderer

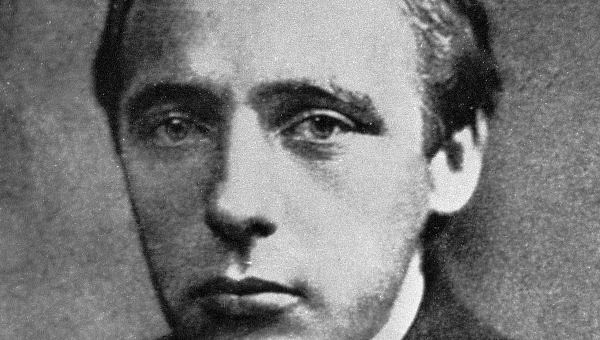

Velimir Khlebnikov was born 130 years ago. An avant-gardist, poet and writer prone to experimenting with the Russian language, he was the progenitor of the Futurist movement, a daring verbarian and President of Planet Earth.

He died almost a century ago, but people still argue over his legacy. Was he a genius or a scribbler? A schizophrenic or a prophet? Were his poems ludicrous or revelatory? Did he believe in his art or was it all a sham? A strange, lonely, penniless and gaunt wanderer in torn burlap trousers, he did not, in Nikolai Aseev’s words, look like a poet or even a human being. What he did look like was “a long-legged pensive bird” whom everyone treated with tenderness yet bewilderment...

Of course, he didn’t become Velimir overnight. At first he was Viktor, son of ornithologist Vladimir Khlebnikov and historian Ekaterina Verbitskaya. His place of birth, however, was rather exotic: Malye Derbety, Astrakhan Governorate—in other words, steppes, Kalmyk Buddhists, overall romanticism. But the family didn’t live there for a very long time: the father had to travel, and the Kalmyk steppes gave way to Volyn, then to Simbirsk, to Kazan… Khlebnikov was destined to roam the earth all his life. He could never rest his body (being a wanderer with no home or family to himself) or soul—he was always searching, changing himself and his environment, inventing something. To a sensible person, he was a pauper, a vagabond and a loser.

In 1903 he enrolled at a university in Kazan to become a mathematician. That same fall, he took part in a student rally and served a month in prison. He dropped out of the university and came back, this time to study ornithology. And study he did: he went on a couple of expeditions, published several articles and discovered a new cuckoo species. But he gradually lost interest in ornithology and took to Symbolism and the expressive Japanese language.

The Pan-Slavist

Khlebnikov entered a period of “word coinage”: he ecstatically wrote poems, some of which he sent to Symbolist Vyacheslav Ivanov. Sometime later, in 1908, they met, after which the student wrote a hundred more poems and a play, The Mystery of the Distant Ones. Feeling weary in Kazan, he decided to move closer to the poetic community and got himself transferred to the St. Petersburg University.

In St. Petersburg, he paid tribute to the Symbolists’ fascination with the pagan Rus and wrote Snowhite, a play for which he invented snowleens, laffones, Birchpeace and other quasi-Slavic deities. At the time, he became a supporter of belligerent Pan-Slavism, calling for the liberation of East European nations through armed struggle in his Appeal of Slavic Learners. Still, his fearsome Pan-Slavism was soon abandoned along with ornithology.

Velimir Is Born

Finally, the Vesna magazine published his A Sinner’s Seduction, a prose fragment that surprised a lot of readers with its linguistic experimentation.

In 1909 Khlebnikov came to Svyatoshyn, a neighborhood of Kiev, to visit his relatives. There, he fell in love with Maria Ryabchevskaya and dedicated several poems to her. But it went nowhere, like many times afterwards: Khlebnikov loved women and courted them in a funny, childish manner, notably trying to impress Vera Petnikova, who was married, with his swimming prowess. He never married, or, as he wrote himself, “I have tied the knot with Death; therefore, I’m married.”

After returning to St. Petersburg, Khlebnikov frequented the “Academy of Verse” in the so-called “Tower” at Vyacheslav Ivanov’s apartment. He was still ambivalent about his university studies, planning to study Sanskrit at first and then opting for the Department of History and Linguistics. It was at that time that Velimir was born.

Although Khlebnikov socialized with Symbolists, they were hardly enamored with him and never published his works in the Apollo magazine. As for Khlebnikov, he was already pining for something different. He left the “Academy” in early 1910 and made new friends, among them the Burliuk brothers, who invited him to live with them for a while.

This is when his arguably most famous poem, Incantation by Laughter, was written:

O, laugh, laughers!

O, laugh out, laughers!

You who laugh with laughs, you who laugh it up laughishly

O, laugh out laugheringly!

O, belaughable laughterhood - the laughter of laughering laughers!

O, unlaugh it outlaughingly, belaughering laughists!

Laughily, laughily,

Uplaugh, enlaugh, laughlings, laughlings

Laughlets, laughlets.

O, laugh, laughers!

O, laugh out, laughers!

The Futurian

Khlebnikov and the Burliuks founded their own literary community, The Futurians (Budetlyane), which was the first Russian Futurist group, and published their first book, A Jam for Judges. The literary world was outraged: “This collection is full of childish escapades in bad taste, its authors primarily trying to shock the readers and tease the critics,” Valery Bryusov wrote.

The Futurians were eventually joined by Vladimir Mayakovsky and Aleksei Kruchenykh. Khlebnikov quickly became friends with the latter: Kruchenykh was a like-minded person—the inventor of Zaum and the author of the iconic phrase “dyr bul shchyl”. That same year, in 1912, Khlebnikov published his new book Teacher and Student, presenting the “laws of time” (and predicting the 1917 revolution—could it be that he really discovered some kind of “time laws”?).

By 1912, the Futurians started calling themselves Futurists and published A Slap in the Face of Public Taste. In the accompanying manifesto, Burliuk, Kruchenykh, Mayakovsky and Khlebnikov called for throwing “Pushkin, Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, etc., etc. overboard from the Ship of Modernity.” About half of the poems comprising the collection were written by Khlebnikov—whose works, including the famous The Grasshopper, did not receive a uniformly enthusiastic response. Critics considered lines like “Zin! Zin! Zin! sings the raucous racket-bird! Swan-white wonder! Brighter, brighter, bright!” to be overwritten ravings of pretentious mediocrities. However, the books were sold out rather quickly. Meanwhile, Khlebnikov almost got into a duel with Osip Mandelstam, for reasons unrelated to literature. The duel did not occur, and the opponents stayed friends.

The Lord of Time

By World War I, Khlebnikov gave up on the Futurists. He was thinking of joining the Guild of Poets, but the movement was on its last legs at the time. And then the war came, prompting him to look for historical patterns that could prevent wars in the future. Contemplating the “laws of time”, he realized that all important events in Pushkin’s life took place every 317 days. Why, he had always suspected that the number 317 was extremely important with regard to people and nations! In that case, the Society of Presidents of Planet Earth he founded in 1916 would have to bring together 317 best people from across the globe. Apart from Khlebnikov, the list included Vladimir Mayakovsky, Vyacheslav Ivanov, Nikolai Aseev, Dmitry Burliuk, Rabindranath Tagore and H. G. Wells.

So what if our “President” was somewhat insane? He was always adrift, given to staying at his friends and acquaintances, so introspective that he could confuse a matchbox with a piece of bread. When on a visit, he could sink into a reverie and sit quietly in a corner; people forgot about him and locked him down in an empty house, but he didn’t even notice. He carried his manuscripts in a pillowcase. Borrowing books, he tore pages out as he read them, as they were no longer needed. He wrote with an eagle’s feather or a porcupine’s quill. He kept forgetting to eat or wear overshoes, let alone earn money. Pretty clothes annoyed him: if he saw an acquaintance in a lovely hat, he could snatch it off and trample it. He pretended to forget everything—or did he? When he bought a new shirt, he threw the old one out of a window. He considered himself Pharaoh Ikhnaton, Omar Khayyam and Lobachevsky. At the time of the civil war and revolution, he traveled across the country aimlessly. When asked why he did that, he said haughtily, “a genius goes his own way”…

Was he a madman, then? Many believed that. Khlebnikov knew—and he took advantage of this perception, first in 1916, when he was drafted into the army—he was examined by various medical panels for a year, received a leave of absence in 1917 and never came back—and then in 1919, when he could be drafted into Anton Denikin’s army in Kharkov, but preferred spending time at a psychiatric hospital.

The Wanderer

Khlebnikov marked the February Revolution with writing poems, reviving the “Presidents” and traveling to Kiev, Kharkov, Taganrog, Tsaritsyn and Astrakhan (he came up with a new name for it, Volgograd, but another city used it later). Going back to Petrograd, he wrote A Letter to the Mariinsky Palace: “The Government of Planet Earth has ruled that the Provisional Government should be provisionally considered nonexistent.” Two days later, the October Revolution took place. Was he a prophet? After all, he did write that he wouldn’t live to be older than 37—and he died at 36.

Having marveled at the revolution in St. Petersburg, Khlebnikov went to Moscow, then to Nizhny Novgorod and Astrakhan. He stayed there for a while, having gotten a job at a newspaper. But he couldn’t stay in one place for too long. He left for Moscow, since a book of his was going to be published there, but then he unexpectedly departed to Kharkov, and his Lunacharsky-approved collection never saw the light of day. In the fall of 1920 Khlebnikov found himself in Baku. An anti-government revolt took place in Persia at the time, and Khlebnikov joined the Baku-based Persian Red Army as a lecturer. In Persia he made friends with dervishes and served as a teacher for a Khan’s children for about a month.

Alive

When he came back to Russia, Khlebnikov continued his wanderings. He lived in Baku; worked on Tables of Destiny, a treatise on the “laws of time”, in Zheleznovodsk; was a night watchman in Pyatigorsk, where he wrote poems Night before the Soviets and Chairman of the Cheka; went back to Moscow and became a member of the official Poets’ Union. Disliking the NEP Moscow, he traveled further, all the while working on his supersaga (another genre of his own invention) Zangezi.

And then he fell ill with a fever. His friends advised him to have a rest in a Novgorod Governorate village. But he got worse. There were no qualified physicians in the area. The country doctor said that the patient would quickly recover after spending time at a local hospital. Soon Khlebnikov lost the use of his legs, contracted gangrene and was released from the hospital. He died on 28 June 1922—like he expected, just before turning 37. He was buried in the Ruchyi village. In 1960, he made his final journey to the Novodevichy Cemetery in Moscow.

Velimir Khlebnikov died almost a century ago, but people still argue over his legacy. One thing is certain: he was a phenomenon, and Russian avant-garde would be very different without him. And without his strange, barely readable texts, many authors—Mayakovsky, Platonov, Aseev, Kharms, Pasternak—wouldn’t be the same. Khlebnikov was sometimes called “a poet’s poet”—there is no doubt that his poetry is not appealing to an unsuspecting public. Nevertheless, he influenced even those who never read anything: it was he who, allegedly, coined the word лётчик (pilot), and were it not for him, Russians would still call pilots aviators.

Daniil Kharms, To Viktor Vladimirovich Khlebnikov (1926)

With his legs crossed,

Velimir sits. He’s alive.

That is all.

New publications

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.

Mikhail Kalatozov, a director who transformed the world of cinematography in many ways, was born 120 years ago. He was a Soviet film official and a propagandist. Above all, he was capable of producing movies that struck viewers with their power and poetic language.  Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.

Ukrainian authorities have launched a persecution campaign against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC), the biggest one in the country's modern history. Over the past year, state sanctions were imposed on clergy representatives, searches were conducted in churches, clergymen were arrested, criminal cases were initiated, the activity of the UOC was banned in various regions of the country, and monasteries and churches were seized.  When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

When Nektary Kotlyaroff, a fourth-generation Russian Australian and founder of the Russian Orthodox Choir in Sydney, first visited Russia, the first person he spoke to was a cab driver at the airport. Having heard that Nektariy's ancestors left Russia more than 100 years ago, the driver was astonished, "How come you haven't forgotten the Russian language?" Nektary Kotlyaroff repeated his answer in an interview with the Russkiy Mir. His affinity to the Orthodox Church (many of his ancestors and relatives were priests) and the traditions of a large Russian family brought from Russia helped him to preserve the Russian language.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.

The leaders of the Friends of the Great Russia cultural association (Amici Della Grande Russia) in Italy believe that the Western policy of abolishing Russian culture in Europe has finally failed. Furthermore, it was doomed to failure from the beginning.  Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."

Name of Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko is inscribed in the history of Russian theater along with Konstantin Stanislavski, the other founding father of the Moscow Art Theater. Nevertheless, Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko was a renowned writer, playwright, and theater teacher even before their famous meeting in the Slavic Bazaar restaurant. Furthermore, it was Mr. Nemirovich-Danchenko who came up with the idea of establishing a new "people's" theater believing that the theater could become a "department of public education."  "Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...

"Russia is a thing of which the intellect cannot conceive..." by Fyodor Tyutchev are famous among Russians at least. December marks the 220th anniversary of the poet's birth. Yet, he never considered poetry to be his life's mission and was preoccupied with matters of a global scale. Mr.Tyutchev fought his war focusing on relations between Russia and the West, the origins of mutual misunderstanding, and the origins of Russophobia. When you read his works today, it feels as though he saw things coming in a crystal ball...