![]() — Russkiy Mir Foundation — Journal — Articles — “Differing views should not be confused with falsification of history”

— Russkiy Mir Foundation — Journal — Articles — “Differing views should not be confused with falsification of history”

“Differing views should not be confused with falsification of history”

“Differing views should not be confused with falsification of history”

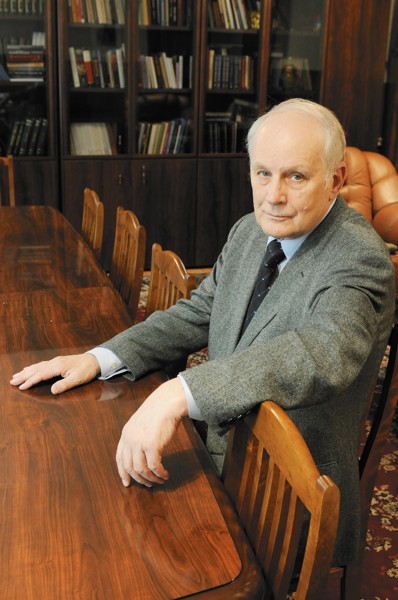

We spoke with Andrei Sakharov, director of the Institute of Russian History of the Russian Academy of Sciences, about historical-informational wars, problems with the creation of a general history of countries of the CIS and principles for the formation of a historical worldview.

– Is falsification of history something that can have an impact on this field of study?

– History has been falsified in eras and times. I am very circumspect with regard to this phenomenon. After all, there are malicious distortions, for example, of the results of World War II, the post-war situation in Europe and a re-evaluate of the results and consequences of the Nuremburg Trials. Georgia is falsifying history with regard to it becoming part of the Russian empire. In Ukraine there was also a period in which issues were falsified with regard to its inclusion in the Russian empire. Such phenomena should be counteracted based on a system of facts and an academic evidentiary foundation. There is no other way.

However, there are also debatable instances which are simply an expression of various points of view, for example, on the Soviet period of the history of Russia. These are differing views, and shouldn’t be confused with falsification. The problem with differing views or interpretations is not global in nature and should not be raised to the political level. This is something on the level of academic discussion. Following discussion a consensus view should be developed and this then becomes the history. So I suppose that’s the way it will be, despite the contradictions and varying interpretations, for the history of the CIS.

– But due to historical-information wars between countries of the CIS we see a substantial amount of divergence in the interpretation not only of the Soviet period but also of the Second World War and even the Battle of Poltava…

– I am not one to take too seriously the information wars and trends seen I the actions of the leadership of a number of countries of the CIS and Baltic region. It is not a matter of divergent interpretations: I am convinced that [divergent interpretations] are unavoidable and useful to the truth and historical science. And not for the sake of historical-information wars but in that when the leaders of neighboring states continue to think in Cold War categories and see Russia as a geopolitical opponent, then this is something in which politicians must engage.

– How do you perceive the attempts to reassess the results of the Second World War? Particularly in countries upon which the USSR, after liberated them from Fascism, imposed the communist ideology, for which they equate the USSR with Fascist German and intend to demand retribution from Russia for this ‘occupation’?

– I don’t believe there is any need for alarm. There is no saying who might try to think up a way to live off others. I am convinced that such profit-seeking and money grubbing is not intended focus of the Presidential Commission on Counteracting Falsification of History. The interim results of its work include the creation of Russian-Latvian and Russian-Ukrainian commissions of historians to resolve issues of our shared past. This is a classical solution: the commission is removed from the countries bilateral relations, turning the issue over to historical science. If the disputed moments of our common history are continually discussed at the highest level, as Poland did earlier with regard to the Katyn tragedy, or, even worse, through information wars which Russia is being engaged in by Georgia, former president of Ukraine Yushchenko or the acting president of Moldova – then this is a dead end. Such provocative approaches are capable of destroying pragmatic and healthy new beginnings in our contemporary history.

– You probably know that according to surveys, when asked who won World War II up to 9% of young Russians say that the Americans did. How can the historical memory be formed in so a way so that we do not forget that the USSR, headed by the dictator Stalin, made the decisive contribution to victory in the Second World War.

– Who is to blame for the fact that they think like that if not the state and authorities? You simply must work assiduously: build a clear system of evidentiary concepts supported by historical facts. And promote them in society and the world – through mass media, youth and other forums. And you don’t need to be shy about bringing up the issue of the role of the USSR in victory over fascism. And historic dates and anniversaries should be used to substantiate this. And we need special programs devoted to the roles of the United States, England and France in the Second World War. We should clearly explain why these countries took so long in opening a second front while the USSR for nearly four years practically fought Fascism alone. We shouldn’t minimize the contribution of our allies through Lend-Lease – weapons, food and medical supplies, etc. That also is a fact. But history should not be distorted and one cannot claim that this was the main cause of the victory over Fascism. We paid dearly for this victory, losing more of our citizens than anyone else in the world. Our society was set back by decades in terms of economic development. So it would be unfair and historically inaccurate to assert that Lend-Lease and the belated second front led the path to victory.

– Would it be appropriate for Russia to use the experience of Germany in forming the historical worldview of its citizens?

– The experience of the Germans in assessing the role of Germany in the Second World War is invaluable. In recent years in German major academic works have been published on the history of the war and evaluation of the role in it of Germany, the USSR, USA, England and France. These works are largely well-referenced and grounded in a solid documentation. There are among them, or course, works that attempt to whitewash Nazism. But I don’t count them. On the whole, the contribution of academics in Germany to understanding the war is invaluable, which forms the objective and open worldview of its citizens. As for the legislation in Germany with regard to the results of the Second World War making it a crime punishable by prison to deny the accepted point of view, my position is the same as for the similar draft law in Russia. Repression legislated by laws do not assist in the formation of healthy historical thinking. The existence in law of prohibitions of certain viewpoints speaks of the complexes of a nation.

– But the Russian commission on the falsification of history is also apparently considering the possibility of developing and adopting a law by which people could face three years in prison or fines of 100,000 to 500,000 rubles for distortion of history…

– I am against such laws. Considering Russia’s experience in fighting against different viewpoints, any repressive measures could result in enormous injures to the public consciousness. Such proposals or draft laws have not been placed before us on the commission. And if such proponents arise, I will be implacable.

– In Russian society there remains a certain degree of caution with regard to your commission, as some see it as a means to fight against the undesirable. Do you think you are risking your reputation?

– I understand people’s weariness. The entire history of the USSR was full of manipulation. The usually stereotypes suggest: here are some more manipulators. But if you don’t allow yourself to be distracted by the negative and the stereotypes, then is becomes clear that the commission could play an important role in cleansing history from mistakes and intentional distortions which prevent us from developing freely. So as an academic I am not ricking my reputation. To the contrary, I believe that the commission will become a conduit for absolutely verified and balanced assessments of our history.

– Are you at all concerned over the number of representatives of government power structures in the commission?

– They are needed. For example, people from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs are more informed that academics about distortions of Russian history that come from abroad. The FSB is represented by its archive service. By the way, the secret services of the United States and Great Britain still haven’t opened their archives from the WWII era, whereas Russia has. Here is a simple example – the story of Holodomor. When people began to accuse Russia of ‘genocide of the Ukrainian people’, we turned to the FSB, which had material that had both already been declassified and some which was still secret at that time. We historians used these materials in the polemics with our Ukrainian opponents, showing their documentation insufficiencies and at times outright lies. We proved that Yushchenko and his circle characterized this crime just as one of ‘genocide of the Ukrainian people’. This was a malicious falsification aimed at creating conflict between the peoples of Ukraine and Russia. As a result of our communication with Ukrainian historians, we came to the conclusion that there truly was a horrible famine and there were serious violations of the law that doomed many people to die of hunger in Kazakhstan, in Russia and in Ukraine.

– How great is the temptation for members of the committee to please authorities and at their prompting take up the cause of the state positions?

– If the interests of science and the state coincide, then what is wrong with that? To the contrary I am convinced that this is just great. If the interests of science and the state diverge or I sense a certain ideological directive or pressure, then I am sure that you must clearly, calmly and consistently make your corrections. And assert them. That is how I will position myself. I don’t see myself having any other sort of role in the commission.

– In 2011 the Commonwealth of Independent State turns 20 years old. There are complex talks underway on the possibility of creating the first History of the CIS under the editorial guidance of academics of all the countries. However, the historians from Georgia left the group just as Georgia itself left the CIS. Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan have withdrawn from consideration practically all chapters related to their own history. Kyrgyzstan is constantly rewriting its history. And then there are the irreconcilable views of Azerbaijan and Armenia with regard to the Nagorno-Karabakh. Under such conditions is there any chance that the History of the CIS will ever be completed?

– Yes, but not necessarily by the anniversary. After all, there is also the problem that in many countries of the CIS textbooks on the history of the independent states has either not yet been written or has been written in such a manner that it is rejected by a substantial portion of society. While I won’t say which countries, but I have read and seen many history textbooks of CIs countries, and I must admit that what I have seen does not stand up to any sort of academic criticism. Many university history textbooks, unfortunately, either belittle or insult the history of neighboring countries. Self-validation at the expense of neighbors is perhaps the first sign of the immaturity of state education programs and the country’s elite. The problem lies in the fact that many national elites instead of focusing on the creation and assiduously building the state and formation of the nation’s worldview, they head down the path of creating the image of an enemy out of a neighboring state. How? By creating myths and a mythologies which distract their people from true history and modernity.

– What should be done?

– Here I see two problems. First, let the myth creators write their stories, but that need to be separated from the science of history. For this to happen, we need to political will power both within the countries and at the level of the entire commonwealth. And this is actually what the national leaders of CIS countries are talking about. And I think that given a little time things will fall into place.

The second problem is more complicated. In Ukraine, Belarus, Kazakhstan and Russia, for example, several redactions of various textbooks on national history have been published. However, even the historians cannot always reach agreement on some particular events. In Russia, for example, this means the very painful civil war of October 1993. Imagine how difficult it is to reach an agreement with groups of academics from various countries working on the History of the CIS when each group has the various interest groups of their own countries’ elite watching over their shoulder?

But that is point of good neighborly relations and reconciliation – we need to reach agreement through an academic and evidentiary foundation of facts. It is another matter that the quickly approaching anniversary does not give us enough time to produce a fundamental and balanced view of the past. I wouldn’t rule out that these complicated negotiations over the creation of the History of the CIS will take more than just another year or two. But for the 20th anniversary, most likely, the Commonwealth will produce a picturesque album or perhaps some general theses on our common history. It’s better this way – slower than we would like by methodically and sequentially, to form the historical memory of our citizens based on the principles of historism and mutual respect, and not mythmaking.

Author: Vladimir Emelyanenko