![]() — Russkiy Mir Foundation — Journal — Articles — Get Down to Culture, Gentlemen!

— Russkiy Mir Foundation — Journal — Articles — Get Down to Culture, Gentlemen!

Get Down to Culture, Gentlemen!

Get Down to Culture, Gentlemen!

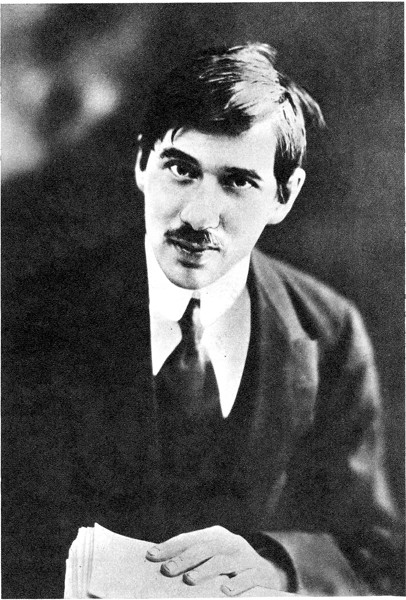

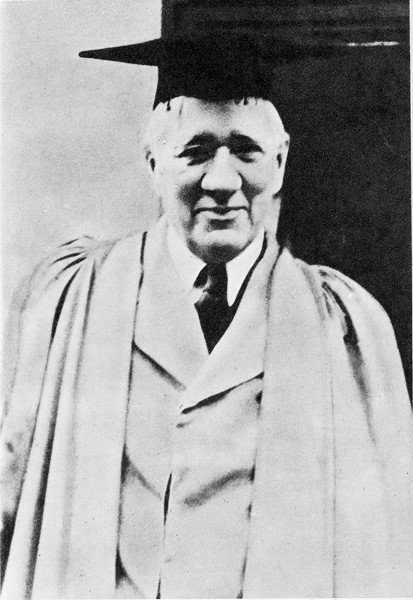

At first glance it may appear that the life story of Korney Chukovsky is one of astounding success: a boy from Odessa born out of wedlock to a laundry girl became the most widely published Russian writer and Emeritus Doctor of Literature at Oxford University. Starting out in a semi-basement, at the end of his life journey he had everything his unpretentious compatriots could only think of: a dacha in Peredelkino, an apartment on Tverskaya, a car and a lot of money for repeated editions of his books that became classics and bestsellers. He basked in popular love and received readers’ letters by the sacks. But was he happy?

As you read into the pages of his diary, the long familiar portrait of a gray-haired gentleman with a sly smile on his face reveals heretofore unnoticed features: bitter folds at the mouth and inhuman wistfulness in the eyes. Chukovsky’s diary can be read only by the strong in spirit, for it’s hard to slog through some pages, full of turbid and black despair. Indeed he suffered so many losses during his long life that it’s unfathomable how he could endure all that woe. He outlived three of his four children, his wife and many close friends. He was repeatedly fired, publicly disgraced, expelled from literary circles and seemingly weaned from the printing press forever. But each time he recovered and struggled further on.

The Beginning

He was baptized as Nikolai and his patronymic was entered into church records after the name of the parson who performed the rite – Vasilyevich – though they should have written Emmanuilovich. His father Emmanuil Levinson, the son of a physician from Odessa, studied in St. Petersburg, where he took with him his maid Ekaterina Korneychukova. Over the course of several years two children, Marusya and Kolya, were born unto this couple. Later their father forsook them, after his family found him a wealthy bride. His mother went back to her hometown with her kids, where she earned her living as a laundry woman. Her children drew water for her all day long. The neighbors did not greet his mother Ekaterina on the street and Kolya had the stigma of a bastard. Even after he grew up and was writing articles for a local newspaper, he did not know how to answer questions about his father and patronymic.

Otherwise he had the ordinary childhood of an Odessa boy who was running through the courtyards, fishing, playing, collecting post stamps and going to a tedious gymnasium. He was very good at humanities and rather bad at mathematics and physics.

Nikolai was quick-tempered and explosive – he often pounced on his offenders with his fists, and ranted and raved at home. He was expelled from the gymnasium – apparently from the seventh grade, rather than from the fifth as he himself wrote everywhere – and not because of his “low origin”, but for publishing a handwritten magazine, which was strictly forbidden for grammar school students.

As a teenager he butted heads with his Mom, ran away from home, rented housing, worked as a house painter, and learned English using a self-help manual, writing out English words on the roofs with a brush. He read a lot – not only poetry, but also books on philosophy and economics. He read passionately and at random, shaping his own worldview on the basis of the stuff he read, like many other thinking young fellows of his days. This approach later helped him to form his views on the role of art and literature in human life, which he never changed later on. Those views crystallized into a plain tenet: art is made for the sake of art, beauty and harmony. Literature is an absolute category – it cannot and should not serve any special purpose.

Later he reworked his “peasant’s” last name Korneychukov into the familiar pen-name Chukovsky for his first publications. Chukovsky’s lifetime credo was that aesthetics is the only reliable criterion in the assessment of any work of art.

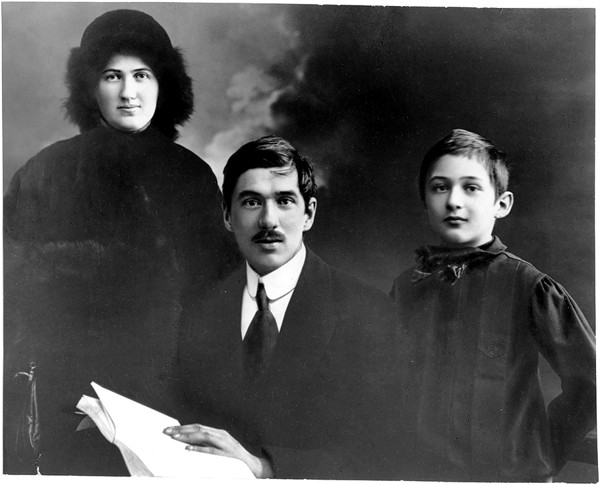

Kolya Korneychukov showed his treatise to his friend Vladimir (Ze-ev) Jabotinsky, then a young correspondent of the Odessa News (later their paths diverged – both gave up journalism, but one of them for the sake of literature and the other to fight for Israeli statehood). Jabotinsky took his friend’s work to the editorial office where it sat around for a while and then eventually saw light – the author was even paid a royalty. When a question arose who could be sent to London as a newspaper correspondent, Jabotinsky recommended Chukovsky, since the latter spoke English. Chukovsky immediately married his girlfriend Masha who came from a good Jewish family, but ran away from home and got baptized for the sake of this matrimony. The young couple then made their way to the United Kingdom. They were pressed in their budget and had to move from one boarding-house to another, all being poky holes of a place. Instead of working as a correspondent, young Chukovsky attended the Library of the British Museum on a daily basis and was eventually offered a job of the compiler of Slavic catalogues there.

Revolution

He came back to Russia when the newspaper stopped paying him, full of vivid impressions and new experience. After London, Odessa seemed too cramped and chintzy a place – he was attracted to St. Petersburg where he tried to get employed as a correspondent, but to no avail. At home his little son, also Kolya, waited. He had to do the breadwinning, being still a young guy in his early twenties; and frankly speaking, he was good at very few things. Yet London’s lessons sharpened his pen and taught him to be terser and more pungent than before – his earliest reports were oppressively verbose and cumbersome. The new Chukovsky was noted for a concise writing style, but nobody hastened to offer him employment.

Then the Revolution of 1905 broke out, the rebellious battleship Potemkin moored at the Odessa port and the city stirred up. Chukovsky visited the battleship with a group of young guys overexcited at the unheard-of events – they just brought the rebellious sailors some kvass to drink and took from them their letters to loved ones and friends. Then he was watching a night fire in the harbor and subjection of the rebels. He saw the corpses of the sailors gunned down and burnt in the fire taken away. From then on, he was burning with enthusiasm for the revolution and could not think or talk about anything else but the savage act of brutality committed in his eyes. He wanted to be part of revolutionary events but did not know what he could do…

In the fall he set out for St. Petersburg again where he began publishing the satirical magazine Signal, having capitalized on the Czar’s manifesto about the freedom of press. Soon a criminal case was initiated against the magazine’s editor for mocking the authorities. He was incriminated in several offenses – from insulting the members of the royal family to calls for an overthrow of the regime. This criminal case lasted until 1907, leaving Chukovsky unwilling to meddle in politics afterwards.

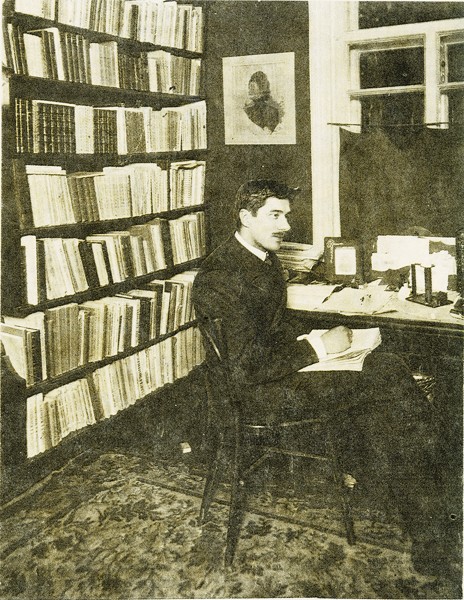

Criticism

By that time he had already moved to Finnish Kuokkala not far from St. Petersburg, where inexpensive summer homes could be rented. There was no metropolitan fuss there and he had his own study in the midst of woodland and sea. Suffering from insomnia since his youth, Chukovsky was quite comfortable there. The second child was born into his family. His work for numerous minor periodicals finally bore fruit: the young star of Russian literary criticism won acclaim and invited to work for the Rech newspaper published by the Cadets Party. This is where Chukovsky published his best modern literary criticism.

He delivered a lot of lectures on literature. He was a born lecturer, holding swap over his audience very tenaciously, striking them dumb with his sudden comparisons and plot twists. The readers and listeners wondered, whether it was indeed possible to look at a writer through the prism of his texts, while he assured them that the text exposes all secrets of any writer, even some of which he himself is ignorant.

Rescuing Literature

His quickly growing children made him ponder on the development of a child’s psyche, the development of linguistic skills, children’s creativity and works for kids. He read books to his own kids and could not but lament over mediocrity of most of them. And he started composing children’s stories himself. He came out with his Crocodile maybe for Kolya and maybe for Boba, his third child. This famous poem first saw light in 1916.

In the years of WWI Chukovsky traveled to England in the company of Alexei Tolstoy, Vladimir Nabokov and several other people to see how the allies were waging that war. From there he wrote several large correspondences for the Niva (“Crop Field”) magazine.

Upon his return from England Chukovsky borrowed money and redeemed the summer home where he lived. Soon the Revolution broke out and his “dacha” was left in the now independent Finland on the other side of the border, while the Chukovskys who went to the city, where their kids were to go to school, got stuck there.

The Revolution brought famine and unemployment. Chukovsky even sold newspapers with his eldest son. Korney also bartered his lectures for foodstuffs and additional food rations for his family. Printers came to a standstill: there was no paper, and writers and poets were hungry. Chukovsky planned to rescue Russian literature from perdition, having gathered men of letters in habitable premises, where they could warm themselves, have something to eat, talk to each other, deliver lectures on literary subjects and hear news about who was writing what… Maxim Gorky helped him get both a building and money for this undertaking. The House of Arts proved instrumental in the survival of many writers, poets and artists during that hungry winter.

Fairytales

He was a worker of culture by vocation and his homeland then needed cultural work as never before. And he agreed to do this daily, ungrateful, at times boring and at times inspiring work: educating the reader. Until the mid-1920s he had been able to write what he thought and have his works published. But soon they began tightening the screws and very soon he had to give up literary criticism that could bear the constant ideological pressure. As was his custom, Korney changed his pursuit at the juncture of epochs to tackle something new. He then focused on rearing his daughter Maria, the fourth, youngest and perhaps the most beloved child in the family. She was happy to benefit from his mature and mellow fatherhood – games, talks, verses… He told her his favorite fairytales – this was how Dr. Doolittle and other translated verses saw the light, in addition to his own that were coming in floods.

By the late 1920’s clouds started gathering over his head. At first his daughter Lida was brought to justice for membership in a political circle and exiled from Leningrad. Some time later collectivization began – not only among the village people who were forced into collective farms but also among the writers. Fairytales were proclaimed a noxious relic of the past and Chukovsky was treated almost as a saboteur. He was compelled to repudiate his fairytales, to admit his own folly and to promise faithful service for the cause of socialism. Torn with the socialist critique which demanded that the books by Chukovsky be thrown out of all libraries, weaned from writing, Chukovsky consented. He promised to write Merry Land of Collective Farms, a book of new songs and ditties about collective farms for Soviet children, and ripped himself apart in doing so. He could not forgive himself this move during the rest of his life and regarded a terrible disease of his daughter as the punishment for his cowardly heart.

Terrible Sadness

Maria developed bone tuberculosis. They did not know how to cure that awful ailment – the patient was just placed in a mild climate and prescribed a nourishing diet with the hope that her health would improve and the immune system could fight the disease better. But food was not in plenty, the famine of the early thirties was impending and mild climate was the only hope. Maria, who went blind in one eye, with plaster on her both legs, was transported to the Alupka Sanatorium in the Crimea where they tried to treat such children. The sanatorium was noted for savage discipline: a child would be taken away from his or her parents who were not allowed to see them. To make his way to his daughter, father had to invent some non-existent journalist’s assignments and to write essays about that sanatorium for Novy Mir, or to visit the kids as a children’s writer… The Crimean climate did not help and in 1931 his daughter died. Chukovsky aged badly and came back to Moscow with gray hair and with half of his soul “amputated.”

Meanwhile there were signs of change in Moscow. The authorities modified their attitude towards writers who were no longer traduced, defamed or attacked. The party denounced the excesses and began showing respect for the writers, publishing their books, paying salaries to them, and resettling them in new apartments. Little by little Chukovsky, knocked almost senseless with his grief, gained a new lease of life. In those days Chukovsky saw the best way to cope with his depression and despondency: helping other people. “You need to amplify your heart,” he wrote on one occasion, “letting in other people with their woes and helping them.”

He could no longer write fairy-tales, for he repeatedly stated that a children’s writer must be a happy person. Literary criticism was also off limits for him. He engulfed himself in the study of Nekrasov and translations. He also put his mind to building libraries in earnest and teaching literature at school, having written many brilliant articles on that subject.

When the years of repression began, he helped the children of convicts, put good words in for people in prison and those who slipped into obscurity. His son-in-law, husband of his daughter Lidia and talented physician Matvey Bronstein, was one of them. The stranglehold was gradually tightening on his family. He could hardly persuade Lidia into leaving Leningrad – her arrest warrant had already been issued; the secret police were going to accuse his son Kolya of spying activity… For some unknown reason repressions were suspended before they caused any harm to Chukovsky’s family – we’ll probably never know why. But staying in Leningrad was dangerous and so in 1938 Korney moved with his wife and son Boba to Moscow. Soon they were granted a dacha in the new writers’ community of Peredelkino where Chukovsky spent the next 30 years.

Outcast

Here he could work in calm and quietude. This did not last long, however: no sooner had the home in Peredelkino been rendered habitable, than a war commenced. His both sons were fighting on the frontline – his beloved Boba perished in autumn 1941 near Moscow while his eldest son Nikolai witnessed the dreadful dying in blockaded Leningrad.

Korney himself wrote articles for Sovinformburo and later, evacuated to Tashkent, he helped the kids in evacuation find their families and wrote Children and War where he related how intelligently children of the nation at war helped adults in their work. He came up with an almost unfeasible idea: telling the little ones what the war was all about and explaining them in the language they could understand what adults were fighting for. He placed himself on the rack, rewriting his book again and again, reading it to kids in hospitals and schools, and checking how they perceived the fairytale Prevailing over the Villain.

Finally he published it in Tashkent and tried to publish it in Moscow. But the fairytale where valiant beasties were riding on tanks and guarded against hyenas on the offensive was taken by many as barbed wit over the woe and exploit of the Soviet people… Chukovsky made another attempt to write a fairy-tale in post-war years. There was a dacha and peaceful summer in his Bibigon. Midget Bibigon in a cocked hat was bravely fighting against a turkey cock and rescuing his sister Cincinella from the dragon.

Children were delighted to listen to the new fairytale over the radio. They sent heaps of letters to Chukovsky where they vied in inviting Bibigon to their places, sending him their drawings and gifts… He even wanted to arrange an exposition of these touching letters sent by the kids who had just survived the terrible war. But Bibigon too was branded as a vulgar, apolitical and malign character. They destroyed many sacks of letters at the radio station and there was no exhibition.

During the next several years down to Stalin’s death and the “thaw” Korney lived as an outcast. He was writing articles in honor of the jubilees of great writers – Chekhov, Nekrasov, Shevchenko and others. He did his best to conserve Nekrasov’s heritage, restored those phrases in his poems that had been deleted by Soviet censors and prepared his works for publication.

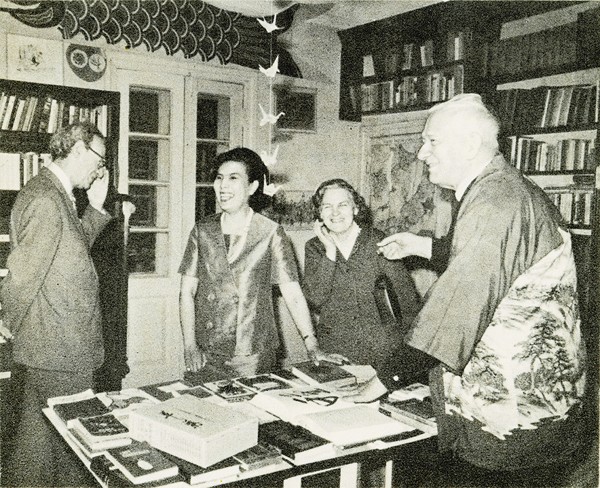

During the last decades of his life, when the sultry atmosphere of late Stalinism gave way to the enthusiasm of the “thaw”, he was busy disseminating culture and explaining the competent ways of writing verses for kids, teaching literature to them, doing literary translations, speaking Russian and writing in Russian, evading platitudes and two-penny stock phrases. He boisterously rejoiced at new talent, defending it against persecution, pleading for Vasily Aksenov and Joseph Brodsky. Solzhenitsyn lived at his dacha for long periods of time…

Chukovsky’s home in Peredelkino, like his cottage in Kuokkala, turned into a center of gravity for the Soviet intelligentsia. He was visited by poets, writers, translators, pedagogues and foreign delegations. In their eyes he was not just a children’s poet, critic, student of literature and translation theorist – he was a living embodiment of Russian culture, somewhat cut down during the Soviet years and yet alive and undefeated.

On Happiness

How did it happen that this grammar school dropout in ripped pants turned into an incontestable authority in Russian literature at the end of his life? Probably the secret is in his tremendous willpower and incessant self-education. “Every morning I raise a scourge over myself,” he wrote near the very end of his life. Continuous reading in English and Russian, ongoing daily toil, regardless of weather conditions or the state of his mind and soul, regardless of the political climate in the country. Work was his way of escape, his joy and his curse. He worked systematically throughout his lifetime, evolving into a true Russian intellectual. Chekhov had always been his moral compass; he learned from him to be gentle and kind with people and, following Chekhov’s example, he built a children’s library in Peredelkino. During his entire life he had unselfishly served Russian literature on which he commented back in 1906: “Literature is absolute.”

Was this gray-haired patriarch of Russian language arts, sly grandpa surrounded with little ones and lonely literary wolf really happy in his long and hard life? In his diaries we do not only find the abyss of hopelessness, but also the dazzling ascents of joy, when the whole world seemed to be dancing around: the sun in the sky was reeling in a dance, bats on the roof were waving with their kerchiefs and dancing, tears of joy were standing out on birch-trees, and oranges were ripening. Being a depressive man of mercurial temper, he could share that joy as nobody else – in his fairytales, where good overpowering evil pushes the boat out, and in his critique where he did not only rebuke mediocrity but also revered the genius of Tolstoy, Chekhov and Blok. Throughout his life he had discerned the beauty of the language, style, human soul, the world around and could share this beauty with the reader. Perhaps for this very reason he withstood all the blows of merciless fate.

Author: Irina Lukyanova